A crow cawed from the far side of the nasty thicket. Another answered from the ridge that overlooked the River Raisin’s bottomlands, well to the west. The first cawed twice; the second cawed twice. The first crow uttered a pitiful, drawn-out squawk that sounded nothing like a crow’s caw. The second cawed twice, sharp and crisp in tone.

A black-capped chickadee landed on the tip of a barren sprig, two trade-gun lengths to the right. The twig bobbed up and down. The nasty thicket crow cawed once. The chickadee canted its head. The ridge crow cawed twice. The two black demons hollered back and forth for a good ten minutes. Neither seemed interested in venturing to meet the other. The chickadee moved on after a half-dozen banters. It wasn’t wasting its day sitting still.

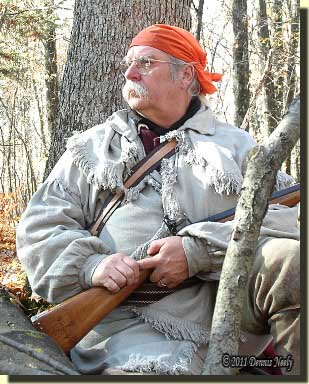

On that cold, late-October morn in 1794, the fox squirrels stayed in their abodes, at least on the west hillside that overlooked the nasty thicket. It didn’t take a traditional woodsman long to agree that the chickadee’s choice was the best option. After looking about, I rose to my feet, stretched out stiff muscles, then checked the prime on “Old Turkey Feathers,” my Northwest trade gun.

On that cold, late-October morn in 1794, the fox squirrels stayed in their abodes, at least on the west hillside that overlooked the nasty thicket. It didn’t take a traditional woodsman long to agree that the chickadee’s choice was the best option. After looking about, I rose to my feet, stretched out stiff muscles, then checked the prime on “Old Turkey Feathers,” my Northwest trade gun.

Lazy white clouds drifted west, pushed by a cold, northeast wind. The acidic fragrance of fallen oak leaves mixed with a telltale dampness, hinging that a cold rain might arrive before nightfall. Now and again the bright sun poked through, offering a fleeting few moments of welcomed warmth. Only the white oaks still held their leaves. The forest looked ready for the first winter snow.

My wool-lined moccasins struck off to the south, following a doe trail that in past years was churned-up earth, littered with track upon track. Yellow and burgundy and brown leaves laid undisturbed on the trace. Disease had riddled the deer herd. Squirrels, ducks and a wild turkey provided that fall’s table fare.

Up and over a knoll, the broken top of a dead oak obstructed my course. With little mind, I stepped over the largest branch, as was usually my habit. I paused and stood amongst the three main limbs and tangled branches. I pondered about lingering for a while within the top’s shelter. Instead, I turned to my left to take a last look at my back trail.

But I misjudged my proximity to the limb I had stepped over, and in truth, I had shuffled about a bit more than I thought. My left thigh bumped hard into the unmoving, barkless branch that exceeded the size of a three-gallon wine keg. I felt a knife-like pain in the side of my thigh and a tug on my knee breeches as I jerked away. The sharp, spear-like break of an unseen twig scratched my skin and tore the knee breech’s coarse-woven fabric. I spread the cloth; the scratched needed no attention. Disgusted with myself, I stepped out of the tree top with greater care.

The still-hunt continued, and as I skulked along the doe trail, the fingers of my left hand rubbed the scratch and fidgeted with the tear that would need mending that evening.

An Evolving Notion of “Relative Age”

At the end of April I added a topic to the “Basics” section of this website that dealt with artificially aging clothing and accoutrements. “A Progression of Age and Use” generated a fair amount of comments and observations, to say nothing of sparking a few discussions on the topic.

A week ago, while donning the knee breeches I wore that day in 1794, I spied the patch, which triggered a fond memory of how the tear came about. I rubbed my leg as I wondered if now might be a good time to share a change in my perspective on what once was a pet peeve—artificial aging.

Traditional black powder hunters take their living history portrayals a step farther than most individuals who time travel: they pursue wild game in a period-correct manner, and with a little luck, feed their family with the meat of their simple pursuits. One side effect of these exploits is the natural wear and tear the garments, black powder arms and accoutrements receive in the field—to say nothing of one’s body.

Depending on the woodsman (that term includes the ladies, as well), the amount of time spent in the glade, and the harshness of the terrain, I feel historically-correct aging accumulates at a faster rate for traditional hunters than for most living historians, and there are exceptions, of course. But the question that has been bothering me since I first considered aging the split pouch is, “Is the natural process fast enough?”

My bumbling around with a new persona based on an amalgamation of John Tanner, Jonathan Alder and James Smith’s lives brought to light the fact that all of my clothing and most of my accoutrements are “store-bought new.” After coming to that realization, I saw no choice but to add some aging, in moderation.

My bumbling around with a new persona based on an amalgamation of John Tanner, Jonathan Alder and James Smith’s lives brought to light the fact that all of my clothing and most of my accoutrements are “store-bought new.” After coming to that realization, I saw no choice but to add some aging, in moderation.

The purpose for aging the split pouch was to attempt to put forth “an honest and truthful impression” of those three hunter heroes. I had a hard time reconciling “honest and truthful” with “faking age” and a “false representation” of actual use. Despite my misgivings, I found myself forced into taking a deeper look at the progression of age displayed by my entire kit. As so often happens, I mulled over this dilemma while sitting with my back against a favorite red oak tree, and in the end my attitude changed with regard to the need for aging.

When I addressed the split pouch, I used John Tanner to explain the emerging notion of “relative age.” Tanner’s narrative speaks of hunting dawn to dusk, and sometimes into the night. In addition, one might infer from his writings that he slept in some of his basic clothing—his shirt and breechclout, for example. Seven days multiplied by 24 hours per day yields 168 hours of wear per week of Tanner’s life.

By comparison, I started wearing the ruffled shirt on every outing when in my returned native captive persona. By the end of the firearms deer season, if you asked me, I would have said I wore that shirt “mid-September through November,” “all fall” or perhaps “half the hunting season.” To my mind, those eleven calendar weeks amounted to “half a year,” because as a passionate hunter I equate the entire hunting season to a year.

In more quantitative terms, I logged about 200 hours of 1790-era hunting during that time period. Now, assuming Tanner slept in his shirt, one might divide the 200 hours by 24 hours which amounts to a little over eight days of actual 18th-century, field wear and tear time. In relation to John Tanner’s wilderness life, the shirt was a little over a week old. That made sense, and although the revelation was a bit surprising, I accepted it, reasoning the idea is best compared to dog years versus people years.

But the quandary did not end there. Shortly after coming to the “eight days in Tanner’s life” realization I found myself addressing the aging of the split pouch. Being an item made of buckskin, the split pouch should have a longer expected life than a cotton or linen shirt. So obvious questions arose: “Where was the pouch in its expected lifespan?” and “How much visible wear would it have had?”

Those questions began to haunt me, because there seemed to be no reasonable answers, at least none that satisfied me. Then, in the middle of spring turkey season, as I sat against that oak tree, my mind began calculating how much hunting time the ruffled shirt needed to equal a month, then six months, then a year’s worth of wear in the context of a John Tanner year—in essence, the shirt’s relative age.

By comparison, if his shirt lasted a year it would see 8,760 hours of wilderness service (365 days multiplied by 24 hours per day). If, in a full September to March hunting season, I was fortunate enough to log 400 hours of time afield, my ruffled shirt would need just shy of 22 full traditional black powder hunting seasons to re-create the wear and tear his shirt received in one year.

The result of all these mental gymnastics is a reformulation of my opinions and attitudes toward artificial aging. There is no question that I have a lot of cogitating to do on this subject, and no doubt, more words will flow on the topic. For now, suffice it to say I have come to accept artificial aging as a needed and necessary tool in putting forth an honest and truthful impression of 18th-century life.

Moderation is the watchword, however. In addition to the questions above, I now ask myself: “Does the application contribute to the impression, or will it detract from the portrayal,” “Does it blend the individual items of material culture together to re-create a believable image,” and above all, “If I could travel back to 1794, would I arrive unnoticed among the likes of John Tanner, Jonathan Alder and James Smith?”

For now, let me just finish by reiterating that never-satisfied truth that my persona is always in need of mending…

Consider your persona in 18th-century time, be safe and may God bless you.

One Response to In Need of Mending