Green maple leaves fluttered. A light breeze riled the Chicago River. Puffy clouds scurried to the northeast. The air carried strange aromas mingled with an occasional whiff of foul-smelling smoke. Lake Michigan’s waters were but a brief paddle to the east, but out of sight. The cabin of Jean Baptiste Point du Sable stood on the opposite bank, but a hazy fog, not of this earth, all but erased the humble abode’s image from a studious time traveler’s mind’s eye.

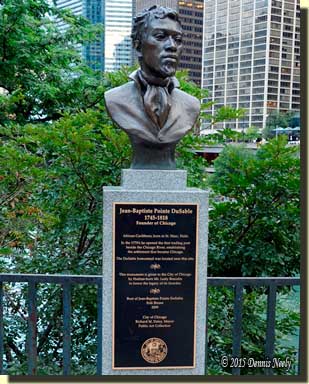

A bronze bust, sculpted by Erik Blome, stands in ‘Pioneer Court,’ built on the du Sable homestead site on N. Michigan Avenue in Chicago, IL.

Evening shadows stretched long. A bark canoe with two forest tenants slowed, turned, then beached on the far shore. Trees grew tall well beyond the backcountry traders post and its outbuildings. Cows, sheep and a few reddish chickens wandered about. Split rail fences bounded a modest garden.

The trader and the Potawatomi visitors gestured, no doubt discussing the three fur bales in the canoe. The exchange seemed friendly, but businesslike…

Then, in a frustrating instant, the heavy “whoosh, whoosh, whoosh” of a dark blue tour helicopter’s flailing rotors dashed the scene with the same certainty as a rapid’s torrent tears and twists and splinters fragile bark canoes. As the invader flew to the west, the chopper’s image reflected off the silvered glass of Trump Tower. The Old Northwest Territory of 1796 passed away…

John Kinzie’s Trading Post

That evening I stood overlooking the Chicago River in a situation that was far from conducive for traveling back in time to the Old Northwest Territory and my beloved 1790s. The river had a greenish, artificial-looking cast to it. Thick, concrete retaining walls lined both banks. Wide, winding sidewalks with steel handrails followed the river’s course. Here and there, grassy patches sported installed trees and manicured shrubs. Blue and white tour boats docked where Pottawatomi bark canoes packed with furs, blankets or traded goods once beached. And every ten minutes or so that confounded helicopter whoosh, whoosh, whooshed overhead to the delight of selfie-stick-wielding tourists much younger than I.

And to compound my time traveling maladies, I felt a compelling need to jump ahead into the first few years of the 19th century, then on to early August of 1812. This task proved near impossible, partly from the distractions that surrounded me, and partly from my lack of historical knowledge of the not-so-distant future.

In the midst of modern-day civilization, I could not help but chuckle as I recalled Professor Jay Anderson’s analogy in Time Machines that living historians are like people in a boat drifting along a winding river:

“Every day, we see evidence of the present, but past and future times are hidden from us around the river’s bend. Still, they are there, waiting for us simply to step out of the boat and walk around the bend into the past. The problem is to figure out how to beach the boat…” (Anderson, 188)

But to achieve Professor Anderson’s lofty goal, a humble living historian must surround one’s self with stimuli from his or her chosen time period—in my case, 1796. This is hard under the best of conditions, but impossible at the intersection of N. Michigan Avenue and E. Wacker Drive in the heart of Chicago. Yet, I had to at least try. My wife Tami is used to the glassy-eyed look I get when my mind jumps over time’s threshold and scampers back. I saw her smile once or twice. She knew…

Long ago I learned historical characters come and go when sifting through the primary documentation associated with a chosen bygone era. Sometimes individuals disappear for years at a time, only to reappear on eternity’s stage through a happenstance or a passing footnote. The mention of William Wells, John Kinzie, Little Turtle and Madame La Framboise always command my immediate attention.

When reading through a narrative, especially one that deals with an actual hunt, I find it very difficult to restrain the historical me. After all, this fictitious personage acts as a vessel to hold a multitude of 18th-century nuggets, and what better way to add to that treasure than by tagging along on a hunter hero’s adventure, one he or she deemed worthy enough to write down? Alas, this mischievous behavior has been the norm for thirty-five-plus years; I don’t expect that will change, at least I hope it doesn’t!

You see, as I read a given historical passage, I can’t help but get caught up in the story. In the best of circumstances, the words evoke emotions and reactions that mirror those described by the author, two hundred years prior. I crave the few fleeting seconds when my simple pursuits parallel theirs, when the context of the 21st-century glade melts away and time knows no boundaries.

Like so many other traditional black powder hunters, I seek to experience what they experienced, to share an instant or two of kinship with a soul that I really don’t know that much about. I say that because it is difficult to sum up a life’s worth of hunting experiences in a few pages of the Draper Manuscripts or in the limited space allotted to a dictated narrative, as in the case of John Tanner.

Years ago the late Chuck Leonard introduced me to The Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly. He insisted I subscribe, simply based on the quality of the research. I took his advice and spent a few more dollars to purchase the back issues, offered as a “package.” I spent weeks reading through those black and white pages. One evening I read an article by Charles E. Hanson, Jr., “John Kinzie and His Gun.”

Kinzie’s years in Detroit caught my attention. His time there predated my chosen time period, but the geographical location and the fact that he was a fur trader of note put him on my “watch list.”

The article told how the Museum of the Fur Trade acquired a long-barreled English fowler with “ribbed brass rod guides and brass ‘dragon sideplate,’ evidently a very early ‘chief’s gun’ or fine gun…” (Hanson, Jr., Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly, Chadron, NE, Winter 1970, pgs. 1-5) The gun’s origin was not known at the time, but the initial cleaning process uncovered Kinzie’s name and initials, along with a silversmith’s personal cartouche.

“…the buttplate is worn and battered, the entire gun shows age and hard usage. It is however, of better quality than the ordinary Northwest Gun…” (Ibid, 3)

On one of my first trips to Friendship, about 1985, I purchased a “damaged/defective” fowler stock blank from Dick Greensides of Pecatonica River Long Rifle Supply with thoughts of copying John Kinzie’s gun. That was before I became so steeped in the Northwest trade gun’s mystical history.

The blank still stands near the workbench. Close friends and family members keep urging me to make a new Northwest gun for Msko-waagosh, my returned captive persona. I’ve looked at that stock a couple of times with thoughts of reworking it into the Northwest gun pattern. The recent trip to Chicago and a similar fowler Wallace Gusler displayed at Friendship have me thinking differently now.

Moderns pass by the bronze plaques in the sidewalk where the northwest block house of Fort Dearborn once stood.

I spent a lot of time roaming all around that intersection that evening. I traced out the bronze plaques inlaid in the sidewalk that marked the supposed walls and block houses of Fort Dearborn. This is where I tried to pull myself into the future, August of 1812.

Here I crossed paths with William Wells, another Native captive, taken at the age of 12. Wells garnered the attention of Little Turtle, the great Miami chief, and eventually married his daughter, Sweet Breeze. With Little Turtle’s consent, Wells became a captain in the Legion of the United States and scouted for General Wayne. He was wounded in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, and died leading the evacuation of Fort Dearborn.

Yet here again is another example of the characters that populated the 1790s in the Old Northwest Territory crisscrossing paths, raising more questions than answers. But more on that another time…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.