Two sharp clucks betrayed a young wild turkey. Beyond, deeper in the cedar grove, a fox squirrel chattered. Sixty yards distant a cottonwood leaf, heart-shaped, palm-sized, still green in the center, whipsawed back and forth in the steady north-northwest breeze.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

Both the turkey and the squirrel grew silent after the Northwest gun thundered. A distant crow cawed; nothing persistent but rather as one just passing through. Black gun powder granules tumbled to the trade gun’s warming breech. Not long after the wiping stick coaxed a linen-patched round ball down the bore and seated it firm on the charge.

A red-tailed hawk kited in from the south. Its graceful image broke into sight above my forehead, not high yet not low in the cloudy afternoon sky. “Scu-reeeeee…Scu-reeeeee!” the raptor screamed as it banked its wings and circled off toward the River Raisin.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

Heavy white smoke raced to the southeast. The cloud expanded and thinned as it filtered into the cedar grove. Some minutes later a pair of blue jays swooped low over the prairie grass, then rose up and perched in the cottonwood’s foliage. I watched the jays as the wiping stick swabbed “Old Turkey Feathers’” fouled bore with a water-soaked linsey-woolsey patch. Once clear of the tube, the greasy-black patch fell with the others in the little pile to the right of the tarnished-brass powder measure.

Heavy white smoke raced to the southeast. The cloud expanded and thinned as it filtered into the cedar grove. Some minutes later a pair of blue jays swooped low over the prairie grass, then rose up and perched in the cottonwood’s foliage. I watched the jays as the wiping stick swabbed “Old Turkey Feathers’” fouled bore with a water-soaked linsey-woolsey patch. Once clear of the tube, the greasy-black patch fell with the others in the little pile to the right of the tarnished-brass powder measure.

With the Northwest gun leaned against the red trade blanket on which the smoothbore’s fixings laid in a neat semi-circle, I turned left and looked at the ragged hole in the practice target. “It’s time to go look,” I whispered. And with that I started walking down range.

Range Time with a Purpose

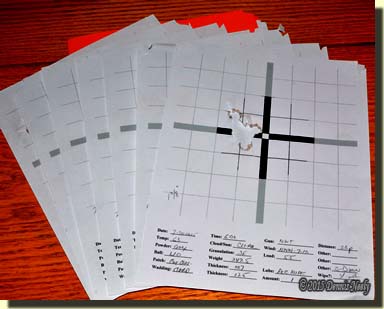

The stapler snapped three times. Being frugal, I use only one staple to hold a target’s bottom edge, even in a stiff breeze. The orange folder, the one that held this go-round’s worth of sight-in targets, acted as a makeshift backing pad as I began filling in the six rows of information, noting the patch lubricant was the variable changed in that five-shot group. Completed, the target slipped into the folder, joining the other fourteen “already shot” samples—the work of three separate range sessions.

Old Turkey Feathers is far from new, being 30-something years young. We’ll leave it at that as it is not considered proper or polite to ask a fine lady her age. But Old Turkey Feathers has temperamental fits, now and again, and those times of wayward behavior earned her a file of targets.

One folder, a dog-eared green one, keeps the 8 by 10 round-ball targets; a special stash in the basement holds rolls of brown-paper pattern board targets. Black felt pen slashes mark each perforation and the total hit count is recorded in the bottom left corner, along with the powder charge, wadding used, shot size, date, time, temperature and other noteworthy information. Some rolls record bird shot, others buckshot, and last fall a new set chronicled the wilderness classroom lessons of buck and ball.

My wife, Tami, questions keeping the growing stack of rolled up pattern-board targets, but when a problem arises the first place I go is the target file or the rolls. On many occasions the answer already exists, and I just forgot or drifted off into a bad habit with unfavorable consequences.

For those readers new to black powder shooting, or those contemplating veering off on the path to yesteryear, most veteran shooters suggest keeping notes of both practice sessions and competitive matches with a new longrifle or fowler. At the dawn of the 1980s, I should have listened to Homer Dangler and the late Paul Griffith and kept my targets with notes. I did not. Like so many memorable lessons in life, I learned the hard way.

Years ago, up Caesar’s Creek at Shaw’s Quail Walk on the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association’s home grounds, a gentleman sat down next to me as I watched shooters bust most of the clay birds thrown. “Honey, how are you doing today? Ever shoot the quail walk?” the gent said. Calling me “Honey” caught my attention, and I later learned that was Max Vickery’s trademark greeting.

Max Vickery was an icon at the NMLRA, a national champion shooter with both rifle and shotgun. “Contagious enthusiasm” best described Mr. Vickery. We talked about chasing pheasants and rabbits, two of his fondest passions. When the conversation reached besting clay birds, Mr. Vickery offered a sage bit of advice: “You need to shoot a thousand birds.”

I’m sure he could tell from my perplexed look that I did not understand. He told me to set a thousand bird goal, each shot taken seriously, which translated into a lot of practice. He suggested spreading the birds over time, and when at Friendship, I should shoot the quail walk as often as I could, regardless of my score. He assured me at the end of a thousand birds I would see a real improvement in my wing shooting skills, and I did.

Mr. Vickery’s advice can be paraphrased to “You need to shoot a thousand round balls,” too. Years ago I lost count at ten thousand. After all, once a traditional hunter reaches a level of proficiency that suits his or her requirements, the only shot that matters is the next one.

Mr. Vickery’s advice can be paraphrased to “You need to shoot a thousand round balls,” too. Years ago I lost count at ten thousand. After all, once a traditional hunter reaches a level of proficiency that suits his or her requirements, the only shot that matters is the next one.

Not long ago a forum thread caught my eye. The original question dealt with what was a reasonable distance for taking a deer with a smoothbore. I have addressed establishing an

“effective distance” in a number of posts on this site and in magazine articles.

The answer is for each hunter to establish his or her criteria as to the group size needed to humanely bring a deer to the table—six to eight inches is common. The next task is to assess the ballistic limitations of the chosen smoothbore and the physical skills of the person pulling the trigger. The distance at which either the arm or the individual can no longer maintain a consistent six-inch group is the outer limit of the hunter’s effective distance. To gain this knowledge requires range time with a purpose.

What concerned me with this particular post was the comments that presented “factual information” that is inconsistent with the targets produced by Old Turkey Feathers over the past 30-plus years. One respondent who is respected for his historical knowledge made authoritative statements based on ten shots with a new-to-him fowler.

To make matters worse, others based their comments and assumptions on the “findings” of the first writer, repeating them over and over without questioning the limited number of shots on target. I do not doubt the person’s results, but his conclusions based on such a small sample are incorrect, and further, support the misconception that smoothbores are inaccurate.

A gentleman used to deer hunt on a neighboring property to the North-Forty. He sat on the same hill with an Ithaca Deerslayer shotgun. He thought nothing of taking running shots, which we forbid on this side of the fence, because of the low probability of a clean kill. Most of his volleys were three to five shots, and the result was the same—no venison.

When we talked, I asked if he ever sighted the shotgun in at a range or practiced with it. He said he had, noting he took “two to five shots” and when “the last one hit close to the bulls-eye” he figured it was “zeroed in.” The same happened in the later years when he added a nice scope—he’d take a few shots and when one hit the bulls-eye he was set to go. He never spoke of adjusting the sights so his point of aim matched his point of impact, yet he felt his gun was shooting “right on,” based on one shot that happened to hit where he wanted it to.

The point I am trying to make is that any testing in the wilderness classroom should be undertaken with a purpose, barring plinking and just shooting for the fun of it. Now the purpose for range time might vary, but the results should be verifiable and easily duplicated at future sessions and especially under actual hunting circumstances.

In essence, someone else with a similar smoothbore should expect to follow the same loading procedures and achieve the same results. If a test result cannot be duplicated, it is worthless unless it contributes to further understanding that moves the individual closer to a solution to a problem or helps improve that person’s skill level.

To take ten shots and report the results of those ten shots is one thing. To use those results to make a definitive statement, one that does not match others’ results, is quite another. And when those statements influence newcomers to shy away from smoothbores, as one person stated, the erroneous findings become a terrible disservice to the traditional black powder hunting and the black powder shooting sports communities.

Give traditional black powder hunting a fair try, be safe and may God bless you.