Sunlight sparkled on fresh frost. A puff of frozen breath foretold of the older doe’s arrival. Ears twitched, then dropped from sight. Her head popped up, but her gaze was off to the north. She flipped her ears back before she turned and stared at her back trail. In time the sleek doe’s back came into view. Ten or so steps closer, she paused and nuzzled the leaves beside the lower trail.

“Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark, ark, ark…” A wild turkey hen made her presence known on the far side of the big swamp. “Ark, ark,” came an answer, down the hill and around the bend from the raspy old hen. A blue jay flew by the humble ambuscade, then swooped up into the forked oak at the swamp’s edge, the one by the middle crossing, just south of the little poplar grove.

Two younger deer walked into sight, the second puffing more than the first. One foraged to the right of the trail, the other to the left. Their mother glanced back, then plodded ahead. The trail snaked to the east of a downed tree top. The parent oak was huge with wide-spreading limbs, the trunk stout and hollow. A heavy gust in the midst of a downpour broke away both of the east-facing branches. Clusters of dead, brown leaves still clung to the twigs. The foliage swallowed up the matriarch’s meandering silhouette.

Two younger deer walked into sight, the second puffing more than the first. One foraged to the right of the trail, the other to the left. Their mother glanced back, then plodded ahead. The trail snaked to the east of a downed tree top. The parent oak was huge with wide-spreading limbs, the trunk stout and hollow. A heavy gust in the midst of a downpour broke away both of the east-facing branches. Clusters of dead, brown leaves still clung to the twigs. The foliage swallowed up the matriarch’s meandering silhouette.

The yearlings browsed behind the oak’s fortification. A white tail flashed in a space where two rum-keg-sized branches forked. The older doe reappeared with a hearty puff, what seemed to be the deer equivalent of a gentle sigh. Leaves crunched in cadence with her hoof-falls.

Straight downhill, maybe twenty-five paces distant, this forest tenant stopped near the base of a modest red oak. She gazed about and twitched her ears. I breathed down, forcing my warm breath over my chin and into the wool trade blanket that hugged neck. I squinted to avoid eye contact.

The doe pawed with hard strokes of her left front hoof. Leaves flew and fluttered, piling up beneath her midsection. Her shiny black nose smelled the upturned earth. She pawed once more, then she nibbled at an acorn, then another, then another.

The two young deer caught up with her. The one that trailed behind sported velvet nubbins. He pushed the young doe into her mother’s hip. The mother turned her head, opened her mouth and pulled her nostrils back, looking as if she was about to bite the rambunctious offender. The button buck pushed again, and mother knew better, choosing instead to utter a low guttural bleat.

The three milled about under that oak tree for a fair amount of time, pawing leaves and crunching acorns. Heads popped up, noses sniffed and ears flipped in all directions. Several blue jays perched overhead, jockeying silent from tree limb to tree limb. Yet, never once did any of these wilderness creatures detect a trading post hunter lurking uphill in a different tree top—a gentle, southeasterly breeze held the smell of death at bay.

On that crisp November morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1794, a Northwest gun, charged with an anxious death sphere, rested across the woodsman’s hunt-stained buckskin leggins. A fine stag was his only concern. The doe and two yearlings were but a pleasant interlude…

“…the first time I ever saw a deer”

The primary purpose of any traditional black powder hunt is to put food on the family dining table, but the woodsman’s goal is to do so in a manner that adheres to the methods used by our forefathers.

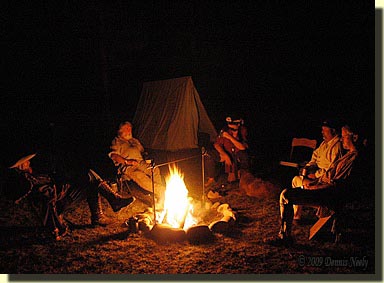

Joseph Doddridge devoted a small chapter in his hallowed recollections to hunting. He begins by stating that the woods supplied a fair amount of the settler’s subsistence. He tells of deer, bear and fur skinned animals, and he describes the hunting camp and names it “a half-faced cabin.” (Doddridge, 99)

When Doddridge speaks about the hunting camp and the conversations around the evening fire, he talks of “the spike buck, the two and three pronged buck, the doe and the barren doe…,” leaving the impression all deer were the object of the hunt. In short, his fellow backcountry inhabitants were, as he said, subsistence or meat hunters. (Ibid, 101)

When Doddridge speaks about the hunting camp and the conversations around the evening fire, he talks of “the spike buck, the two and three pronged buck, the doe and the barren doe…,” leaving the impression all deer were the object of the hunt. In short, his fellow backcountry inhabitants were, as he said, subsistence or meat hunters. (Ibid, 101)

Little is written about Josiah Hunt, one of my favorite hunter heroes. But thanks to a biographical letter by T. C. Wright, we know that Hunt was a hunter of exceptional skill. He provided meat for General Anthony Wayne’s Legion of the United States’ winter camp at Greeneville, Ohio in 1793. (Howe, 199)

On that morning, as the old doe and her two offspring munched acorns not twenty paces distant, I felt like Josiah Hunt was sitting next to me, watching to see if I would take the shot and put meat on the table. The shot pouch held an antlerless and a buck tag, both unfilled, and from the admonitions that floated through my subconscious, I’m sure Josiah knew that, too. But my family had use for one deer, which is part of the reason I passed on the does. Under my breath, I shushed Josiah’s impatient urgings.

Fortunately, from an historical perspective, Joseph Doddridge made provision for my desire to wait for one specific buck:

“Often some old buck, by the means of his superior sagacity and watchfulness, saved his little gang from the hunter’s skill by giving timely notice of his approach. The cunning of the hunter and that of the old buck were staked against each other, and it frequently happened that at the conclusion of the hunting season the old fellow was left free, uninjured tenant of his forest…” (Doddridge, 101)

Recently, research for my trading-post hunter persona found me skimming through George Nelson’s journal. Nelson was fifteen-years-old when he signed on as a clerk with the XY Company. He departed LaChine, bound for the Grand Portage on the western end of Lake Superior, on May 3rd, 1802. Barely underway, Nelson wrote:

“…At ‘Portage des Chenes’ [Oak Portage], now ‘Aylmer,’ the people [voyageurs in his canoe] saw a Red Deer swimming over the West Side, they pursued, overtook & killed it. This was the first time I ever saw a deer.” (Nelson, 37)

I have that passage marked, and when I read it, my mind immediately dashed back to the morning when I watched those three deer scrounge for acorns. I don’t know why, but that’s what I thought of.

At first, I felt a twinge of guilt. As an 18th-century time traveler, I’ve been in countless situations like that morning. I had no intention of unleashing the death sphere at any of those deer. Instead, I relished the opportunity to observe unhindered wild white-tailed deer go about securing their subsistence for that day.

Even though such encounters number in the thousands, I never take the daily comings and goings of God’s creatures for granted. I don’t remember the first time I saw a white-tailed deer, but I have been a part of showing others such wonders, especially the grandchildren.

As living historians, we all tend to put our hunter heroes on pedestals. We hang on their every word, and the good ones we quote back as justification for what we do, what we wear or what we carry. The historical me that emulates the trading post hunter relies on a number of George Nelson’s musings and/or descriptions for such justification. Yet, to a certain degree, I have failed to put or keep his life in a proper perspective.

Nelson was a fifteen-year-old boy who, for five pounds a year for five years’ service, agreed to travel into the wilderness and learn the fur trade. One of his first stated concerns was how “deeply loaded” the bark canoe was and how “the least movement made them swing…often I thought we should upset…” (Ibid, 34)

And then, amidst all of these new sights and sounds and tastes and smells and feelings, Nelson’s voyageurs spot a red deer swimming in the water. “This was the first time I ever saw a deer,” the youthful Nelson writes. What a revelation…

Read a little closer, be safe and may God bless you.