Pesky deer flies failed to dampen that morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1796. Sunlight spears penetrated through the lush canopy, scattering splotches of light hinter and yon upon the forest floor. The aroma of spring greenery and dry, weathered canvas fragranced the air as Msko-waagosh stepped from the wigwam.

Not twenty minutes before, the humble, dome-shaped abode came into view as the forest tenant’s trail-worn elk moccasins left the doe path. Eternity’s threshold lurked somewhere in a flowering patch of wild strawberries, sixty paces distant. Two-plus centuries evaporated without so much as a conscious thought.

Red Fox pushed away the canvas flap. To the left, “Old Turkey Feathers,” his Northwest gun, leaned against the structure’s third rib. A buffalo horn and Odawa-style shot pouch hung from the trade gun’s muzzle. The shot pouch’s woven bead strap, and the plain buckskin strap of the horn, slipped over the woodsman’s gray head and came to rest on his left shoulder. With a quick grab, the Northwest gun became one with his right hand as his moccasins whisked to the west, up through the hidden valley and over the rise.

Red Fox pushed away the canvas flap. To the left, “Old Turkey Feathers,” his Northwest gun, leaned against the structure’s third rib. A buffalo horn and Odawa-style shot pouch hung from the trade gun’s muzzle. The shot pouch’s woven bead strap, and the plain buckskin strap of the horn, slipped over the woodsman’s gray head and came to rest on his left shoulder. With a quick grab, the Northwest gun became one with his right hand as his moccasins whisked to the west, up through the hidden valley and over the rise.

In no time the shimmering brownish ribbon that was the River Raisin appeared in the distance. Unseen from the hill’s crest, Canada geese ke-honked somewhere on the sand flats. Down the hill and out into the bottomlands, a downy woodpecker drummed on a dead white ash. The woodsman’s course turned south with no specific purpose and followed the ridge that overlooked the river. A pleasant morning stroll through an 18th-century Eden was reason enough…

“it’s all ‘stuff’…”

Accoutrement quality found its way into a traditional black powder hunting conversation at Friendship, Indiana, two weekends ago. I was down for the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association’s Spring Shoot. It was a whistle stop visit; I had a long list of folks to see and vendors to visit. I didn’t even take “Old Turkey Feathers” along. Our group grew from three to seven or eight in the course of a short discussion that swelled into almost an hour’s discourse.

“The way I look at it,” a longtime friend and veteran traditional woodsman (who asked to remain anonymous) said, “it’s all ‘stuff.’ You can spend a lot of money, or you can go cheap. What’s important is that you research your persona and try to stick with the common accoutrements that character more than likely had.”

To prove his point, he pulled a well-used tomahawk from his leather belt. “What do you think of this ‘hawk?” he asked, handing the tomahawk to the man to his right who was also dressed as a longhunter and said he dabbled with history-based hunts. The first recipient flipped the blade over in his palm, looking for a touch mark or indication of the maker. He rubbed his thumbnail over a patch of oily rust. A few deep nicks scarred the haft, which showed a nice patina, but not from creative staining or artificial aging. “Well, what do you think?” the owner asked.

“I haven’t got a clue. The shape appears English, rather than French. Mid- to late-18th century, perhaps into the early 1800s; you can see the forged seam; and it looks like a steel bit was welded in. Without a touch mark it’s hard to say, but it’s well made, hand forged and not cast,” he said handing the ‘hawk to the fellow to his right.

“I don’t know, either,” the owner said, shaking his head. “I bought it off a trade blanket. I think I gave thirty dollars for it a dozen years ago. But the size and shape matched one I saw in a museum. The head was found at a trading post…not that far from where I live. That post was only active for ten years, and the time frame matched mine, the 1760s. I’ve hunted with it ever since I bought it.”

A knife with a similar nondescript pedigree joined the show and tell. My friend went on to explain that he puts greater importance on having an authentic looking accoutrement that functions properly than how much he pays for it or who the maker is.

“The point I am trying to make,” he said, “is like most of us, I have limited time to hunt. I want to spend as much of that time in the 1760s forest as I can, not sitting at the computer shopping online or obsessing about the perfect ax or knife or bag or whatever. It’s still all ‘stuff.’”

Authenticity made its way to the fore in this discussion, as it so often does. But the meat of the conversation centered on an honest, well-researched persona from a living historian’s perspective, and the utilitarian side of a given accoutrement from the traditional hunter’s perspective.

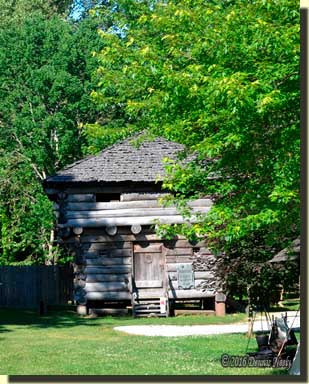

Saturday morning found me up in the primitive camp near the two-story log block house. Two camps shared a common fly, and the occupants were setting out goods on three trade blankets spread in front of the fly. The majority of the items were clothing—lots of clothing—with a few small accoutrements.

Saturday morning found me up in the primitive camp near the two-story log block house. Two camps shared a common fly, and the occupants were setting out goods on three trade blankets spread in front of the fly. The majority of the items were clothing—lots of clothing—with a few small accoutrements.

An average-sized, forty-something gentleman walked over, picked up a pair of buckskin leggins that were in pretty good condition and held them up to his thigh. His wife asked if he thought they would work. He pursed his lips, but did not answer. About then one of the owners who was the same build as the shopper, came over and asked if there were any questions.

The man said he was just starting to assemble “a Rev War scout/hunter’s kit, early 1780s, Pennsylvania country.” I was impressed that he had done some research and at least had the “who, when and where” of living history figured out. Then he pulled out a folded paper from his hip pocket, which turned out to be several sheets of computer paper. The printouts included photos of artifacts and a list of what he needed. He laid the leggins aside in the grass and started looking over the knee breeches next.

In the conversation that followed, I discovered a newcomer to traditional black powder hunting. The gent wanted to expand his club shooting to include the primitive events, but being a hunter, he also wanted to take advantage of Pennsylvania’s flintlocks-only muzzleloading deer season. He said he knew he was going to make mistakes with his purchases, but he wanted to “get going” and not spend a lot of time or money on his first traditional persona. I thought of the conversation from a day earlier.

The fellow tending the trade blanket did his part, too. A former persona of his was similar to what the shopper described, so he picked up items that “went together.” After welcoming him and leaving a card with the URL to this site, I moved on. Before I walked away, the trader had two piles of clothes and was offering his tent as a changing area. “If you are going to hunt in period clothing, you have to make sure each item fits properly,” he said.

So often this type of conversation centers on purchasing a first muzzleloader. The advice is always the same: start with an inexpensive production gun, hunt with it for at least one season and then invest in a better arm once you have a solid idea of your “who, when and where.” This was the underlying crux of the “it’s all stuff” conversation.

In the last couple of years, it seems that more and more newcomers to traditional black powder hunting have come to the hobby with the misconception that “you have to be period-correct” before you ever set foot in the glade. That is not correct and should not be perpetuated by those of us who have frolicked in the 18th century forest with great regularity.

As the soon-to-be Pennsylvania back country scout and hunter said, we should encourage folks to “get going” with a minimal investment and make adjustments from there. I’m just as guilty of this as anyone else. Experienced living historians harp on “period-correct, period-correct, period-correct,” but we fail to remember that we had a bit of a steep learning curve when we started out in the glorious pastime. After all, traditional black powder hunting is all about stepping over time’s threshold and experiencing a joyous romp in our own historical version of Eden.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.