Two wild turkeys squabbled. The rampage continued longer than most; the altercation sounded unresolved. An hour after first light the two began dithering at each other, on the ground, to the south. Blue jays screamed, adding a sense of intensity to the woodland melee. Then all went quiet on that pleasant October morning in the Year of our Lord, 1795.

A fox squirrel bounded from a stout red oak trunk with a modest crackling of crisp leaves. After two short hops, leaves and dirt flew as the bushy-tailed tree rat dug for a breakfast morsel. The acidic aroma of rotting leaves tickled the nose, yet the air smell fresh and clean as it does in mid-April. Perhaps the choice of a downed oak top, its summer foliage intact but browned and curled, accentuated the smells of fall.

Wedges of Canada geese winged to the River Raisin from the southeast. Crows cawed by. A chipmunk scampered along a rotted log. Four chickadees bobbed on the tips of a witch hazel’s slender branches. Then a raspy hen turkey clucked to the north, “Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark.”

“Ark, ark,” a bird answered from just over the knoll to the south. The first bird to speak uttered a soft cluck in response.

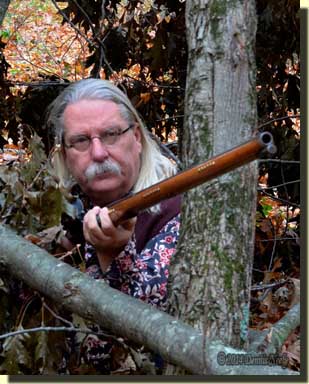

The birds sounded equidistant from the oak-top fortification. The frizzen rose and fell. Sufficient black granules filled the Northwest gun’s pan. A blue-wool clad knee inched up. The trade gun’s forestock rested on the ribbon-festooned leggin. The muzzle hung over the smallest of the three main limbs of the broken trees crown, pointing in the direction of the north turkey. An anxious thumb fidgeted on the smoothbore’s hammer. “Will one bird pass on the way to the other?” “Will they meet out front?” “Will they not show at all?” Such questions churned in a humble woodsman’s mind.

The birds sounded equidistant from the oak-top fortification. The frizzen rose and fell. Sufficient black granules filled the Northwest gun’s pan. A blue-wool clad knee inched up. The trade gun’s forestock rested on the ribbon-festooned leggin. The muzzle hung over the smallest of the three main limbs of the broken trees crown, pointing in the direction of the north turkey. An anxious thumb fidgeted on the smoothbore’s hammer. “Will one bird pass on the way to the other?” “Will they meet out front?” “Will they not show at all?” Such questions churned in a humble woodsman’s mind.

The crunch of steady, yet cautious, footfalls in the leaves grew closer as a wild turkey approached from the south. The bird made no effort to mask its passage. The bulk of the top’s dried leaves formed an almost impenetrable palisade—a positive and a negative asset for the returned white captive who spent his youth tutored in the ways of his adopted Ojibwe family.

“The turkey must pass by before taking a shot,” the forest tenant reckoned. The Northwest gun’s tarnished brass butt plate slipped up to its rightful place against the block-printed trade shirt. With a coordinated flex of the trigger when the thumb pulled back on the hammer, the sharp English flint jumped to attention. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” the hunter prayed in the quiet of his mind…

Documented Priming Powder

Flipping up the frizzen to check the prime is an ingrained habit that dates to the first 1790s adventures with “Old Turkey Feathers.” Although it is rare for me to take another firelock to the field, I follow the same procedure with any flintlock arm.

In those formative years, I loaded the trade gun with 2Fg black powder and primed with 4Fg. I remember a “trial run” on an early-September Sunday afternoon. I carried the new, fringed voyageur bag made out of gold elk hide. An almost-black powder horn hung on a separate strap made of madder-colored wool. The cow horn powder receptacle was made from a kit. Antiqued brass upholstery tacks held the lathe-turned walnut plug in place, just like an “authentic mountain man” showed me. A brass, three-grain, push-type priming flask jostled about in the bottom of the shot pouch

At any rate, I skulked over a rise. A gray, barkless oak trunk threatened great bodily harm. I took careful aim, squeezed the trigger and “Klatch!” Seconds meant life or death. With the gun still pushed into my shoulder, I pulled back the cock and the frizzen in one Fess Parker style “Daniel Boone motion.” Again I took aim at the charging “hostile,” squeezed and “Klatch!” As a last dying act, I dropped the gun from my shoulder and stared into an empty priming pan—I had lost the precious black granules somewhere on my back trail. A memorable wilderness classroom lesson learned…

About ten years ago I focused a fair amount of research on the Northwest trade gun as it related to the trading post hunter persona. No primary documentation mentioned any backcountry hunter in the Lower Great Lakes region carrying a separate priming horn in the late 18th century. Further, none of the trade inventories that supported my character mention a “priming powder” of a finer grade.

A number of times, Francois Victor Malhiot, a clerk for the North West Company, writes of trading “a double handful of powder” for one prime beaver pelt in his 1804 journal (Malhiot, 218). Malhiot doesn’t mention what any of his consumers put the powder in, but other traders do.

The year before, 1803, Michel Curot, a clerk in the employ of the XY Company, sent one of his men to accompany two Native Americans back to their village. He asked Brazile David to guide the pair:

“He [David] Asked me for thirty Balls, his horn full of powder, and one pair of deer skin shoes, and some Tobacco that I gave him…” (Curot, 422)

Like similar passages, “horn” is always singular, and all of the ledgers and trade goods inventories mention only “gunpowder.” With much reluctance, the priming horn with its 4Fg black powder ended up in the shooting box, destined for range work and competitive marksmanship contests.

The next wilderness classroom lesson dealt with priming from the horn, depending upon granules derived from “a double handful of powder.” After all, a major goal of all traditional black powder hunters is to live within the confines of the resources available to our forefathers in a specific time, geographical location and station in life. This is the only way to experience a true sense of kinship with our beloved hunter heroes.

The first time I primed from the horn, the granules looked like river stone in the pan. I fought the urge to count them. A reduced lock time became an immediate concern, followed by the potential loss of game, or worse, the wounding of a majestic forest tenant. No game wandered by, so a tough ethical decision never presented itself that day.

The first time I primed from the horn, the granules looked like river stone in the pan. I fought the urge to count them. A reduced lock time became an immediate concern, followed by the potential loss of game, or worse, the wounding of a majestic forest tenant. No game wandered by, so a tough ethical decision never presented itself that day.

As I so often do when faced with a problem involving Old Turkey Feathers, I retreated to the range for some additional wilderness classroom tutelage. I paid great attention to the speed with which the new priming powder ignited and burned. Much to my delight, I saw little or no difference. Satisfied, I returned to the glade and my simple pursuits.

If I recall correctly, a wild turkey was the first to meet up with the death bees, urged on by powder from the horn. Other game followed as confidence in the larger black granules returned. Today, neither I nor my alter egos give the coarser priming any mind. Sprinkling the pan from the horn is as much a habit as flipping up the frizzen to check the prime.

And that is another unintended benefit of priming from the horn. The fit of the frizzen to the pan on the lock of Old Turkey Feathers has never been tight. The current lock is the best parts of three locks, made serviceable by years of experience, a dash of magic and pure luck. If I remove the mainspring and shake the lock, parts fall off.

To be fair, many of the original Northwest guns I have handled show a similar gap. As a result, 4Fg filters through this authentic space where the coarser granules of 3Fg or 2Fg black powder do not. Thus, I find that I do not have to be as careful about the orientation of the “plane of the pan” as I used to. I lean the smoothbore against a tree, roll it from side to side, point the muzzle down or up, and I still have sufficient priming powder to dispatch the death messenger. I have never tried to fire the trade gun upside down. Hmmmm…

To the northeast, a large, bronze-feathered bird walked from behind a shag-bark hickory. Two steps in the open this old hen paused to survey the forest. She stiffened, then raised her gray head. “Aarrkkk,” she clucked once, stern and demanding. The south bird’s progress halted. A soft “cllkk” placed the utterance ten paces behind the fort and ten paces east. Squinting eyes watched the old hen circle the hickory, then disappear.

The steady cadence of scaly, purple legs walking on brittle oak leaves renewed. A black shape cleared the fort’s northeast corner, well within the smoothbore’s effective distance. Five steps forward, this wild turkey’s keen eye slipped behind two oaks. The Northwest gun swung hard to the right. The turtle sight longed for an opportunity to unleash the death bees. Tail feathers appeared first, sidling side-to-side as the turkey walked straight away. In a handful of heartbeats, the bird emerged, but now too far for a clean, humane shot. With squinting eyes, Msko-waagosh, the Red Fox, had no choice but watch the bird move on to its rendezvous with the old hen…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.