A half-rotted maple stump lurked in dark shadows. Elk moccasins whispered over brittle oak leaves, parallel to a doe trail that followed the spine of a narrow strip of land between two impenetrable thickets. A backcountry woodsman stalked tree-to-tree. A gentle breeze rustled the forest’s canopy, shrouding a moccasin’s occasional crunch. The air smelled of fall, acidic, fresh and dusty dry.

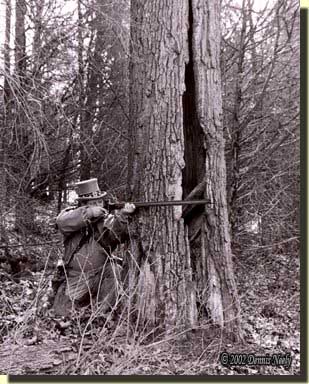

Knowledge of time’s threshold did not exist that mid-September evening, yet an 18th-century truth loomed at a red oak tree with a huge bulge in its trunk, an arm’s length above head-high. The hunter’s course paused behind that oak. Slow deep breaths tried in vain to subdue harried heartbeats.

The as yet unnamed Northwest trade gun’s muzzle poked around the trunk’s south side. The tree hid most of the interloper’s deathly shape. A shaking thumb jerked the English flint back. The sear let out an audible “click” as the steel nose dropped into the tumbler’s full-cock notch. Forest tenants take flight at such utterances, but the stump did not flee.

The flat, shiny-brass butt plate cuddled against the stiff fabric of an unblemished canvas frock. The muzzle fidgeted. Another deep breath induced a sense of calm. The turtle sight settled on a discernible mark the size of a large fox squirrel’s head. The trigger resisted; the flint lunged…

“KLATCH!”

The stomach-churning futility of stone striking steel echoed through the glade. Overhead, a blue jay began an endless litany. The sear bar clicked twice. The frizzen snapped shut. The turtle sight clawed to regain that lethal spot, forty paces distant. A slow exhalation…resistance…

“KLATCH!”

Twice more the trade gun’s mighty lock faltered. Frustration ruled. Concentration on the little turtle suffered.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

Yellow flames belched from the Northwest gun’s muzzle. Thick white smoke billowed. Obscured by the boiling haze, brown leaves and fresh dirt shot skyward a full hand’s width to the right of the moss-covered stump. The sulfurous stench of burned black powder hung all about the red oak tree with the bulge in its trunk. As the gentle breeze blew the smoke to the northeast, the dark grey rock crashed into the frizzen a few more times with nary a spark.

The brass butt plate thumped hard in the dry leaves. The hickory wiping stick slithered forth. A spit-damped patch plunged to the breech and back, over and over. Bewilderment and consternation stoked a bout of careful reasoning. Surrounded by the quiet rattling of leaves, a mature doe appeared to the south, walking the middle trail of the hillside beyond that stump. The precious black granules never tumbled down the cooling bore; the wiping stick never seated a round lead ball firm over the non-existent powder charge. Dejected, defeated by a lowly maple stump, the would-be backcountry woodsman from the 1790s began an agonizing walk home…

Recognizing Unrealistic Expectations

An almost forgotten recollection of one of those first “stump hunts” brought a chuckle and a big smile. In the late 1970s, I graduated from a borrowed, .58-caliber Civil War reproduction rifle to a Northwest trade gun of my own manufacture. Well, as it turned out, graduated is a bit of an overstatement; I sort of oozed into the smooth-bored flintlock amid a host of pitiful whimpers.

An almost forgotten recollection of one of those first “stump hunts” brought a chuckle and a big smile. In the late 1970s, I graduated from a borrowed, .58-caliber Civil War reproduction rifle to a Northwest trade gun of my own manufacture. Well, as it turned out, graduated is a bit of an overstatement; I sort of oozed into the smooth-bored flintlock amid a host of pitiful whimpers.

This new era in my outdoor life arrived with great expectations. In the two muzzleloading deer seasons prior, I pulled the trigger on the 1863 Zouave musket a couple dozen times. Now dear reader, don’t get excited. One of those shots scared a fine 6-point buck that had no idea a human with a front-loading rifle sat amongst the cedar boughs on the west side of the big swamp. The remainder of those hammer-falls unloaded the Civil War musket at a solid stump by the gate leading to the North-Forty.

The Zouave rifle never failed to go off. Once completed, I expected the Northwest trade gun to perform with the same certainty. In retrospect, I thought both the Zouave rifle and the new flintlock smoothbore should possess the same reliability as my 20-gauge Ithaca Deerslayer. The Zouave rifle didn’t let me down, but in hindsight I realized the potential for a misfire was always there. The Northwest gun was a whole different story, starting with those first “stump hunts.”

If I remember correctly, the smoothbore went off three times that afternoon, with a hang-fire the first time, a couple of klatches the second and then the ill-fated last fiasco. The experience was akin to dropping through the ice on the south end of the huckleberry swamp on a snowy February morn—memorable and educational!

As it turned out, the Lott lock’s frizzen was soft, an unforeseen circumstance that required a black powder gunsmith’s intervention. The problem started at the range. For the first few shots, the lock performed as expected. Then klatches found their way into the load-building sessions. Small game hunting season was not open, but thinning hostile stumps was always a possibility. And it was those stump hunts that resulted in an early wilderness classroom revelation: smooth-bored flintlocks, and black powder guns in general, are different from modern firearms!

Now as an aside, I must note that in the last few years I have witnessed a noticeable number of primer misfires with both modern shotgun shells and straight-walled pistol cartridges. In the latter case, three out of 25 cartridges failed to go off. The same doubt has crept into the percussion caps of late, too.

And further, I must note that a “snapped lock” is a “period-correct” occurrence, noted in a number of backwoods journals. I just completed another reading of Alexander Henry’s journal. In his case, the snapped lock occurred while hunting red deer and was caused by wet priming powder:

“…I saw a herd of red-deer approaching. Desirous of killing one of them for food, I hid myself in the bushes, and on a large one coming near, presented my piece, which missed fire on account of my priming had been wetted…” (Henry, 133).

Joseph Doddridge shares a bear hunting story in his famous “Notes…” that alludes to the constant possibility of a flint lock snapping without ignition of the main powder charge.

“It is said, that for some time after Braddock’s defeat, the bears, having feasted on the slain, thought that they had a right to kill and eat every human being with whom they met. An uncle of mine, of the name of Teter, had like to have lost his life by one of them. It was in the summer time, when bears are poor, and not worth killing; being in the woods, he saw an old male bear winding along after him; with a view to have the sport of seeing the bear run, he hid himself behind a tree; when the bear approached him, he sprang out and hallooed at him; but cuffee, instead of running off as he expected, jumped at him with mouth wide open; my uncle stopped him by applying the muzzle of his gun to his neck, and firing it off; this killed him in an instant. If his gun had snapped, the hunter would have been torn to pieces on the spot…” (Doddridge, 23).

Likewise, Jonathan Alder, an Indian captive, tells of an altercation with a youth from his adoptive tribe who “was warring in nature:”

“…Some few words passed between us and in a fit of passion, he jerked his rifle off his shoulder and pointed it right at me. He was standing only ten feet away, but before I could reach him, he snapped it at my breast well loaded and primed. I grabbed the muzzle of his gun and drew out his ramrod and whaled him with it until he begged like a good fellow…” (Alder, 71).

A flint lock is a machine. It will function as intended when it is cared for and in good working order. A part of that care is maintaining a sharp flint, and making sure that rock is secured in the hammer’s jaws. A hammer that is loose on the tumbler axle, play in the bridal and a soft frizzen can all result in a lock snapping. As I discovered from the stump hunts, the firelock’s owner is responsible for “managing the machine” if he or she wishes to attain a high level of reliability from the arm.

A flint lock is a machine. It will function as intended when it is cared for and in good working order. A part of that care is maintaining a sharp flint, and making sure that rock is secured in the hammer’s jaws. A hammer that is loose on the tumbler axle, play in the bridal and a soft frizzen can all result in a lock snapping. As I discovered from the stump hunts, the firelock’s owner is responsible for “managing the machine” if he or she wishes to attain a high level of reliability from the arm.

Not long ago I had a conversation with a frustrated traditional black powder hunter. A fowler that was new to him klatched more than he thought it should. He called from the range and described the symptoms of the sporadic ignition—one klatch about every five shots.

We walked through the possibilities, each of which he had already checked and “eliminated.” In the midst of his muttering, he stated that “once or twice” the flint’s edge did not seem square with the frizzen face. He said when he checked (which was more than once) the jaw screw was tight. With my urging, he pressed the flint from side-to-side, then again tested the jaw screw’s tension.

He said he wrapped the flint in buckskin, “in the usual manner”—an oblong piece with one layer on top and one layer on the bottom of the rock. I asked if he had a piece of buckskin or cloth that could be wrapped around the flint, side-to-side. With great reluctance, he agreed to wrap the flint so at least two layers of buckskin covered the flint top and bottom. He called back that evening and said, “I don’t believe it, but that fixed the problem.”

This remedy evolved after I missed a 10-point buck because of a klatch. I determined the flint was “kinda loose;” one layer of buckskin was not enough to hold the rock firm. By trial and error, I learned to manage the machine…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

2 Responses to Learn to Manage the Machine…