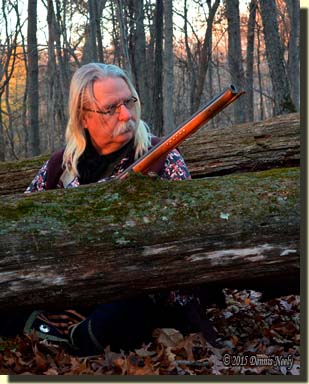

Leaves rustled. A wild turkey offered a weak gobble, muffled in the River Raisin’s bottoms. A gray squirrel materialized, bounded once and commenced digging. Leaves and pieces of leaves flew along with tiny scrapings of earth. The squirrel’s nose burrowed beneath the layered, brown skeletons of the summer prior, then emerged with a mold-encrusted acorn.

This forest tenant ran by the downed red oak top, passing three trade-gun lengths distant. It leaped to a standing oak, clenching the tree waist high, measured on a tall British ranger. Spiraling upward, silvery tail flicking and twitching, the gray squirrel circled around the trunk, then perched on a stubby branch, rotted and broken off years before. On that warm, pleasant morning in May of 1795, that squirrel partook of a fine breakfast.

This forest tenant ran by the downed red oak top, passing three trade-gun lengths distant. It leaped to a standing oak, clenching the tree waist high, measured on a tall British ranger. Spiraling upward, silvery tail flicking and twitching, the gray squirrel circled around the trunk, then perched on a stubby branch, rotted and broken off years before. On that warm, pleasant morning in May of 1795, that squirrel partook of a fine breakfast.

For the second time that morning, the returned captive woodsman reached into his shot pouch and retrieved a single wing bone. He cupped the round end in his hands, placed the flatter end to his lips and sent a sharp, snappy “arrkk” in the direction of the river bottom.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!”

Again, the tom turkey sounded weak and perhaps uninterested. The utterance emanated from the same location: the fallen trees at the sedge grass cove. Either the bird had not moved or another took his place.

Chipping sparrows, two cardinals, a handful of chickadees, and a wandering robin filled the glade with hushed, but joyous music and merriment. Now and again a crow cawed from the hardwoods on the far side of the River Raisin. Several geese jabbered at the sand shallows. And in time, a red tailed hawk circled overhead.

Msko-waagosh sat motionless. His dark brown eyes panned right-to-left, then left-to-right. The woodsman who spent his youth among the Ojibwe centered his attention on the little knoll and the dip to the northeast. If the tom came looking for the mysterious hen, he would pass over the knoll or stroll through that valley…

A Hunter Hero’s Material Culture Outline

The creation of any history-based portrayal, whether founded on an actual person who lived in a chosen time period or a fictional character built from the life stories of two or more individuals, starts with gathering and analyzing first-person accounts.

First and foremost, my research centers on hunting tales, harrowing or mundane. When I read an article in one of the living history magazines or peruse a new 18th-century book, I spend a fair amount of time scrounging through the bibliography. Any books that cover 1790 to 1800, or as in Mi-ki-naak’s case 1763, garner my attention. Some I already have in my library, others go on the infamous “Dad’s book list,” a wish list that gets run through the online booksellers every now and again.

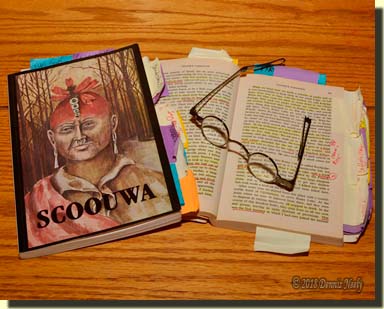

SCOOUWA: James Smith’s Indian Captivity Narrative, sits on top of shelved books, along with the missives of John Tanner, Jonathan Alder, Mary Jemison and anthologies of captive narratives edited by Frederick Drimmer and Colin G. Calloway. These books have been my “go to” research sources in the last few years for the returned captive persona of Msko-waagosh, the Red Fox.

Yellow, purple, blue and orange sticky notes, most with notations, protrude from page edges. This indexing system is fine, if I can remember which author wrote what—which is not that often. Early on in this journey to yesteryear, I highlighted passages in yellow, underlined important phrases in red and penciled notes in the page margins. I added the sticky notes, which act like file tabs. A few thousand sticky notes later I still spent hours rummaging through tabs to find two or three sentences that stuck to the cobwebs of my mind.

Yellow, purple, blue and orange sticky notes, most with notations, protrude from page edges. This indexing system is fine, if I can remember which author wrote what—which is not that often. Early on in this journey to yesteryear, I highlighted passages in yellow, underlined important phrases in red and penciled notes in the page margins. I added the sticky notes, which act like file tabs. A few thousand sticky notes later I still spent hours rummaging through tabs to find two or three sentences that stuck to the cobwebs of my mind.

One evening, in the midst of an exasperating quest, Miss Tami, the ever efficient business system analyst, suggested I establish a searchable data base. The first choice was MS Access. This program worked great for short passages, but anything over a half-dozen words became cumbersome. I tried just keywords, but some historical statements lost too much meaning when reduced to two or three words. I had the same results with MS Excel, too. Even the cyber version of the wilderness classroom can be cruel at times.

One technical aspect of my writing process includes the occasional word search using the “Find” tool under “Editing” on the MS Word tool bar. A week or so after the data base failures, in the midst of scribbling a manuscript draft, I needed to find a passage. As I typed two words, the “Eureka!” light came on.

I stopped working on the manuscript, opened a new document and saved it as “John Tanner Material Culture” in the “Msko-waagosh” file within the “Persona Development” file. Fingers flew on keys. A page number followed the crux of a highlighted passage:

“…drawing his tomahawk…” (5)

“…had some blankets and provisions concealed… (5)

“…gave me a pair of moccasins…” (6)

“…put them in a small kettle…” (7)

“…mukkuks of sugar…” (9)

I paused about twenty pages into Tanner’s narrative, The Falcon… I opened “Find” and started testing. This outlining system worked and required no more set-up time than MS Access or MS Excel.

Two or three evenings each week are devoted to research, depending upon how tired my eyes are. Instead of reading, the next few nights I banged keys with great delight. The highlighting and sticky notes helped, but I found myself skimming the text—rereading Tanner’s life story. The skimming discovered passages missed in prior readings. Of course, those phrases made it into the outline. Eleven typed pages later, 280 pages were reduced to a searchable document, complete with page references.

James Smith’s narrative, SCOOUWA… was next. Smith’s writing style required longer passages for the outline, because his sentences were more detailed, many including an additional explanation:

“…I saw Russel’s Seven Sermons…brought from the field of battle…” (26)

Outlining a hunter hero’s writings removes the words that are necessary to move the narrative along in a smooth, cohesive manner. For a living historian studying the material culture of a given place, time period and station in life, the great revelation of cutting to the basics is the amazing list of resources, accoutrements and daily items available to the individual who currently sits on the examining table.

One page in the outline might cover twenty to fifty pages in the hunter hero’s narrative. Spread out over that many pages, the items appear sparse and sometimes unrelated. Put in outline form, those same pages compress. To some degree, each outline page represents a shopping list of goods the original writer once possessed or that were commonly owned or used by those around him or her.

A general picture develops when passages follow each other in close order. “Breech-clout,” “powder, bullets, flints,” “a pair of scissors,” “silver bands,” “new ruffled shirt,” “garters dressed with beads,” “leggins…with ribbons,” “a pipe,” “tomahawk,” and “flint and steel” become golden nuggets when viewed back-to-back. The context of each passage must be taken into account, as well as other passages that refer to these items. And of course, the commonality of usage is best confirmed when compared to other authors of that era.

But the significance of any outline is this compression of thought, hunting experiences or material objects. The initial investment of time to set up the outline pays great benefits when creating a new persona or tweaking an existing historical portrayal. A word search finds the passages pertinent to a given topic in short order, saving hours of rummaging through sticky notes or thoughts scribbled in margins.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.