Leaves rustled. Quiet followed. The acidic aroma of fallen oak leaves perfumed that October afternoon’s woodland hush. Three delicate crunches coaxed the smoothbore’s muzzle uphill. The turtle sight paused at a gnarly shag-bark hickory tree festooned with muted gold foliage. Two pops and a solid crunch betrayed the fox squirrel’s approach. But alas, the tangle of downed limbs, grape vines and arching raspberry switches concealed the evening meal’s exact location. Milkweed tufts drifted from the edge of the sedge grass.

Tiny claws scratched on harsh gray bark. The tip of a furry, auburn tail twitched past where the first main branch joined the hickory’s trunk. Another burst of solitude… Impatient fingers brushed away dirt from the stretched knee of the dark-blue wool leggin. Four stick-tights clung to the copper-colored silk ribbon that bound the leggin’s front flap. The woodsman’s thumb returned to the trade gun’s lock and traced lazy circles on the jaw screw.

Tiny claws scratched on harsh gray bark. The tip of a furry, auburn tail twitched past where the first main branch joined the hickory’s trunk. Another burst of solitude… Impatient fingers brushed away dirt from the stretched knee of the dark-blue wool leggin. Four stick-tights clung to the copper-colored silk ribbon that bound the leggin’s front flap. The woodsman’s thumb returned to the trade gun’s lock and traced lazy circles on the jaw screw.

A blue jay winged low, then swooped to an upper twig of a nearby red oak. That forest sentinel looked east to the big swamp, gazed beyond the massive oak top that hid the returned white captive, then glanced at the ridge crest. The bird’s blue-feathered headdress rose and fell as it surveyed the glade. Never once did those black eyes look at the squirrel or foretell its location.

Minutes piled up. With a mighty, head-high leap, the fox squirrel left the seclusion of the golden hickory. It slipped under the leaves, popped up and bounded three times. With an abrupt jerk, it turned about and began pawing at the earth. Dirt flew, but only for a second or so, then off it ran in the same direction from which it came. And in that instant, the evening’s menu returned to a scrap of venison jerk, broken walnut meats and tepid water. Such was the forest fare on 22, October, in the Year of our Lord, 1796…

Where Do You Re-enact?

When I first started writing about traditional black powder hunting, a black powder magazine editor brushed off an article query with a statement that anyone who shoots black powder and owns primitive clothes is a traditional hunter.

Being new and wanting to represent the hobby in a true and factual manner, I set out to find out if his wisdom was true. That quest took over two years, and his opinion proved to be wrong. That discussion and the subsequent research led to the birth of this blog and a host of magazine articles presenting traditional black powder hunting as an alternative to modern reliance on today’s refined technology.

Recently I had the opportunity to converse with a veteran traditional woodsman. He said he attended a timeline event here in Michigan and told me all about the day. He said he entered into a conversation with a living historian we both know of who maintains a blog dedicated to the past.

In the course of the discussion, the living historian said he did not recognize my friend and did not recall seeing him at the re-enactments he, the blogger, regularly attended. After listing several events, it became apparent that the two traveled in different circles with different time periods and interests. Then the traditional woodsman asked, “Have you been to the woods lately?”

We both laughed, because we have both made that statement who knows how many times. In most instances, the meaning is lost on the listener, and we have come to accept that. Once in a while someone will ask for clarification, but most often not. We recognize that traditional black powder hunting is a solitary undertaking—a living history venue where the participant simply disappears as he or she crosses time’s threshold.

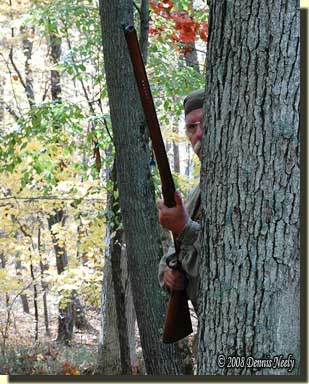

There is no organized re-enactment for traditional black powder hunters. There is no well-trimmed path to what once was, no full-color self-guiding brochure, no yellow arrows painted on brown boards, no cordoned off viewing area, no rustic benches. In the majority of cases, the trek to yesteryear is a one-on-one undertaking with no fanfare and no spectators.

There is no organized re-enactment for traditional black powder hunters. There is no well-trimmed path to what once was, no full-color self-guiding brochure, no yellow arrows painted on brown boards, no cordoned off viewing area, no rustic benches. In the majority of cases, the trek to yesteryear is a one-on-one undertaking with no fanfare and no spectators.

Yes, there are events that feature re-enactors who portray hunters from various time periods. But portraying a longhunter, for example, and re-living the life of a longhunter are two very different journeys. The first occurs within the confines of a viewer friendly historical environment, the second “in the woods” complete with mud and stick-tights, scrapes and bruises, yet unscripted and unfathomable in nature.

On a cold November evening, I pulled Msko-waagosh’s red, wool trade blanket from the back seat of the truck. I draped it over the shoulders of a chilled family member. A few minutes later she remarked with a bit of surprise in her voice how she could feel the wool warming her body. When she went to fold the blanket to return it, she asked about the stick-tights embedded in the blanket’s weave. I laughed and told her Msko-waagosh’s blanket had participated in many 18th-century adventures—re-enactments in the woods.

Not long ago, I overheard a conversation at a living history event. It seems a gentleman who portrayed a longhunter sat around the campfire with an expensive, museum-quality wool blanket wrapped about his body. At the time, the blanket flapped in the breeze from the edge of his dining fly to “air out the smoke smell.” He was sharing how he planned to hang the blanket in his garage when he got home and was bemoaning the possibility of taking it to the dry cleaners to “get rid of the smell.”

I did not mean any disrespect, but I chuckled to myself. My friend, the traditional woodsman, and I take every opportunity to add smoke smell to our blankets and clothing as that beloved aroma is one of the best cover scents in the forest for deer hunting.

And upon further examination, that living historian’s outfit looked clean and well-laundered. The cut of his clothes was period-correct with a fair amount of hand-sewing. His accoutrements were from recognized artisans of the first quality. It was obvious he had done his research. There was some honest wear and tear, but no blood stains, no cuts or tears, no patches, no over-stitching, no dirt or grime or stick-tights.

I remembered being chastised at an outdoor show because the rump of the trading post hunter’s knee breeches carried mud stains and a reasonable amount of soiling. The side-seam was pulled apart a bit, a couple of button holes were frayed and the back of the thigh had a palm-sized patch. And that is just one item taken from the complete “kit” of a given history-based character.

As living historians, we all strive for the best possible time-traveling experience. We seek to drift around the bend and come ashore in our own personal Eden. Some do so within the confines of an organized museum-like setting, while others, like my friend and I, slip away and seek the solitary existence of life in the woods. Such was the forest fare…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

2 Responses to “Such was the forest fare…”