Two red-winged blackbirds chortled. One perched on a flimsy red willow in the swamp, and the other sang from the hillside, not that far ahead. A distant “honk, honk, honk…” emanated from the east, and a series of “ke-honks” came from the River Raisin, a half mile to the west.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl!” rang through the hardwoods that melted into the river bottom, two ridges to the northwest. Dusk approached. Roost time was at hand.

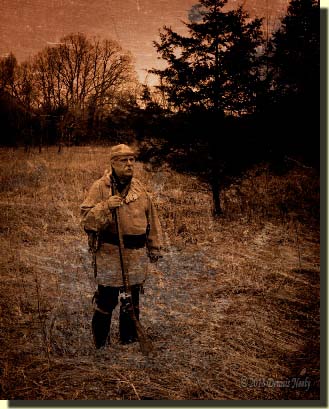

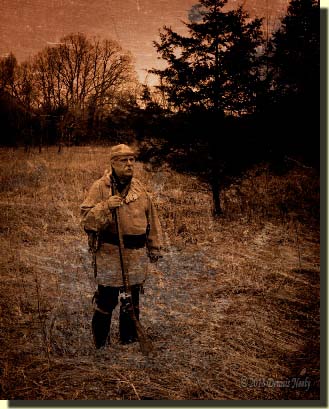

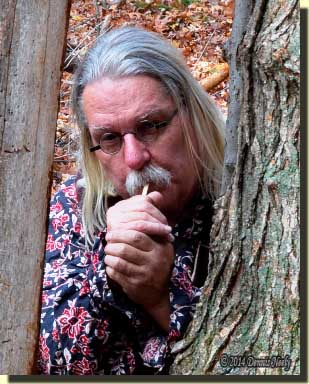

A daguerreotype-style image of that evening’s scout.

“Ark, ark, ark, ark, ark, ark…” a hen near the nameless creek in the big swamp answered. “Ark, ark, ark, ark, ark…” another chimed in from the hidden bog. This bird’s call echoed up and down the long, narrow swamp. “Utt, utt, utt, utt, ark, ark…” a third hen said.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl!”

“Ark, ark, ark, ark, ark, ark…”

“Ark, ark, ark, utt, utt, utt…”

“Gob-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl!”

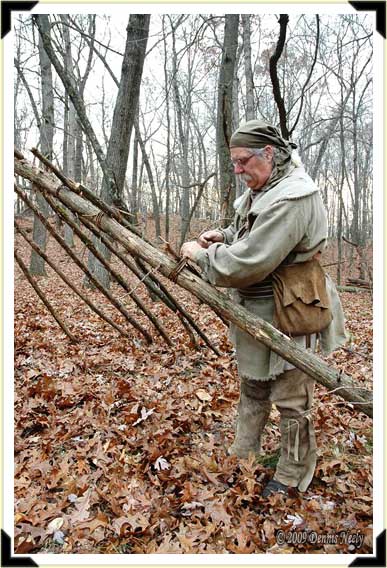

The wild turkey music continued with birds talking over each other as they moved closer to the roost trees on the big ridge. Footfalls followed the lower trails around the east side of the swamp as a backcountry woodsman searched for shed antlers. The air grew damp and heavy.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl!” The boisterous bird, or maybe one of his fellow toms, reached the ridge crest as the clucks and putts in and around the north island moved closer to the swamp’s west cut bank.

“Ark, ark, ark, utt, utt, utt…” The hens’ yelps antagonized the toms, and the constant gobbling from the woods egged on the flock dispersed in the sedge grass and tamaracks.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl!” Moccasins crept up a steep slope, slipping and sliding on the muddy doe trail that angled westward. Partway up the rise, a squabble arose between the north island and the creek’s gentle bend. “Utt, utt, utt, utt!” “Ark, ark, pttt, pttt!” “Utt, utt, utt, utt!”

That evening’s ramble paused in the midst of a barberry patch, offering a higher vantage point to listen to the magical sounds of spring. A definite split among the combatants left at least one hen clucking in disgust as she skirted the island on her way east. Another bird putted behind her.

The cedars surrounding the barberries grew dim. Two geese flew overhead, both missing secondary feathers on their left wings. The right bird uttered a short, squeaky sound over-and-over.

Likewise, the wild hens settled on a six-note, steady clucking. One or two just putted as they crossed the nameless creek and advanced to the east slope of the long, hog-back ridge. Up the hill, near the long beards’ usual roost, one choppy gobble after another beckoned the impending nightfall.

The rush of big wings never fell upon the woodsman’s ears. Moccasins whispered around the tips of a red oak’s fallen top. Solitude settled, accompanied by a faint mist. Years of experience traversing that familiar hill lit the way thru the ebbing gray. The evening’s course passed over the little rise, then dropped down to the edge of a prairie-grass clearing. Oh, what fun!

Compensating for First-time Shooters

A few posts ago I shared an image of a temporary rear sight added to the “Silver Cross,” my wife Tami’s chiefs grade trade gun. The first of my grandchildren began hunting this past fall. He is of slight build, and the modern 20-gauge shotgun pounded his shoulder pretty hard; it kicked him back about 8 inches, to the point he didn’t want to shoot the gun anymore. I told him, and his dad, to be patient, and I would be back in a few minutes.

A few posts ago I shared an image of a temporary rear sight added to the “Silver Cross,” my wife Tami’s chiefs grade trade gun. The first of my grandchildren began hunting this past fall. He is of slight build, and the modern 20-gauge shotgun pounded his shoulder pretty hard; it kicked him back about 8 inches, to the point he didn’t want to shoot the gun anymore. I told him, and his dad, to be patient, and I would be back in a few minutes.

Even with a 12-inch trigger pull, the Silver Cross was a bit long for him. He watched as I measured a light load, added a leaf wad, tamped it firm, measured an equal amount of #5 lead shot, added another leaf wad and seated the load tight. A running narrative explained the loading process, but I knew repetition was needed if he was to duplicate the load himself.

The hearing muffs bumped against the stock; I brought new ear plugs anticipating that problem. He adjusted his safety glasses, but was reluctant to rest the muzzleloader on the bench, much less shoulder it. Based on the first two shots from the modern gun, his skepticism was obvious when I assured him the recoil would be comfortable. Two musket blasts later, he agreed.

His younger brother insisted on shooting, but he is taller and a little heavier in build. By the end of the evening, the two boys were both busting clay birds with the Silver Cross. The load edged up to the minimum for taking a turkey, but neither noticed. Oh, what fun!

We spent several evenings shooting. The first obstacle, aside from all of the new lessons with the muzzleloader, was the lack of a rear sight. Being “period-correct” is of little consequence when a youth is learning to shoot. I didn’t want to dovetail the barrel on Tami’s smoothbore, so I devised a temporary sight: a strip of steel cut from an old joist hanger, bent and notched, then lashed to the barrel with sinew. That addition made a huge difference in shot placement, both for turkey shot and for round ball.

Fabricating a Temporary Open Iron Sight

A number of readers asked for more information on fabricating this temporary sight. To begin with, the sight needs to be the same width as, or slightly less than, the barrel’s top flat, in this case 13/32-inch. Using a square and tape measure, I laid out a line 3/8-inch from the edge of the joist hanger. The length is arbitrary, too, but 1 3/4-inch fit the available steel. I started cutting with a hacksaw.

After cutting out the sight blank, all edges were eased off (top). The roughed-out blank with the galvanizing sanded down to bare metal (center). The start of bending the sight’s upright leg (bottom).

The blade wandered some, but I kept the cut outside the line. A few judicious passes with a mill file trued up the blank to a uniform 3/8 inch. A few more strokes eased the sharp edges and the corners. Since the joist hanger is galvanized and knowing I wanted to paint it flat black, I sanded both sides of the steel down to bare metal.

Using the square, I marked a line at 1/4-inch. This was an educated guess on my part as to how high the sight had to be. I was lucky and hit the right height on the first try—experience shooting trade guns had a lot to do with that choice.

A builder could make the bend equal to the height of the front sight, and then file it down after some range testing. I feel it is important to get the rear sight height correct, so my grandchildren can learn to aim with “a standard” sight picture, not one that requires “compensation”—aim right, left, up or down. That way, they can switch from the muzzleloader to the pellet gun to the .22-caliber rifle with ease. Learning with open-iron sights precedes scopes or peep sights.

I clamped the blank tight in the vise at the 1/4-inch mark (or whatever mark one settles on), and hammered it over to “a degree or three” shy of 90 degrees. Using double faced cellophane tape, I set the upright leg of the sight 4 inches forward of the rear of the barrel. Both grandsons can hold a 2-inch group with the pellet gun at 25 yards. The location of the rear sight matches the same location as the rear sight on the pellet gun, measured from the butt plate. To my eyes, both sights look equally fuzzy.

The Silver Cross needs no compensation right or left when aiming, or said another way, the front sight lines up with the screw slot on the tang screw when shot from the bench. This is not the case with “Old Turkey Feathers.” Clamping the sight base in the vise, I took a needle file and cut a thin groove in the center of the upright leg of the temporary sight. I sanded the burr from the upright, then took it outside and spray-painted it flat black.

The Silver Cross needs no compensation right or left when aiming, or said another way, the front sight lines up with the screw slot on the tang screw when shot from the bench. This is not the case with “Old Turkey Feathers.” Clamping the sight base in the vise, I took a needle file and cut a thin groove in the center of the upright leg of the temporary sight. I sanded the burr from the upright, then took it outside and spray-painted it flat black.

To pad the sight so it didn’t scratch the barrel flat, I added a layer of duct tape on the bottom side of the base. Positioning the sight at the 4-inch location, I started wrapping artificial sinew around the forestock and the sight’s base to secure the temporary sight to the barrel. The base leg did not move, once its entire length was wrapped.

Grabbing the shooting box, I headed to the range to test the sight. The true test came that evening when the grandson’s groups tightened to the point I was comfortable with him shooting at a deer out to 35 yards. I also felt confident unleashing the death bees at a wild turkey. Plus, he said he liked the rear sight better than no sight at all.

Adding a “Peep Sight” to Old Turkey Feathers

A while ago, a long-time reader suggested I should consider adding a peep sight to Old Turkey Feathers. He said he added one to his smooth-bored fowler and it made quite a difference, especially with “these tired, old eyes.”

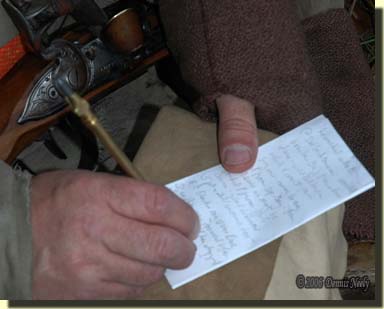

This gentleman, who is an occasional traditional black powder hunter, emailed the suggestion, complete with “primary documentation” from “D. Thomas,” who was captured by the Shawnees, sold and adopted by an obscure Native American band in the southern Great Lakes, supposedly in the late 18th century. He quoted the following passage:

“…a gun of the Northwest pattern with a peep sight at the tang…”

As any good living historian should, I searched out the narrative in an effort to find the complete passage and study its context. A good re-enactor should not trust second hand information, especially anything posted on the internet or contained in a blog post. The meat of the quoted passage is as follows:

“Around 1855, I acquired an old fowling piece, a gun of the Northwest pattern with a peep sight at the tang, the latter being attached not so long ago by a marksman wishing to improve the piece’s looks or to add to its value…” (Thomas, 123)

To say the least, adding a peep sight to a Northwest gun is not period-correct, but this gentleman raised a good possibility for range work. However, I had a hard time following his description for the peep sight. I tried my best to decipher his explanation. In addition, he said he attached his peep sight using the tang screw, which on his fowler ran from the top of the tang down to the trigger plate. Unfortunately, the Northwest gun’s tang screw runs up from the trigger guard and is threaded into the tang. I didn’t think I wanted to make a longer screw, then stack on a nut to hold a sight of whimsical origin.

So, taking the wilderness classroom experience gained from adding the temporary sight to the Silver Cross, I decided to lash a peep sight to the barrel. I scrounged around and found the only peep I had, which was tucked away in a corner of the muzzleloading cabinet. The color concerned me, but if it worked, flat black spray paint could fix that issue. I used double-faced tape to hold it about 4 inches from the breech end of the barrel and started wrapping it with artificial sinew. That process proved a bit messy and time consuming.

Once secured, the first observation I had was that my eyes could not see the front sight, even with the aid of the newly-added rear peep sight. But I persevered and decided to take Old Turkey Feathers to the woods and see what developed in the wilderness classroom.

That night, when the turkey music erupted in all its splendor and magnificence, was the first outing for the new peep sight. I was not impressed, and have since given up on the idea of using such a contraption on Old Turkey Feathers. I’ll live with tired old eyes and a fuzzy front sight, thank you!

Enjoy your April Fool Day, and as I said, don’t believe everything you see in a blog post!

Did I mention that this is my April 1st blog post? Since Easter and April Fool’s Day fall on the same Sunday, I thought I would wait until after church to post this story. Oh, what fun!

Give traditional black powder hunting a try (wink, wink), be safe and may God bless you.

Two steps…a pause…two steps…a pause… Canada geese ke-honked on the River Raisin, from the echoing sounds, beyond the lily-pad flats where the channel deepens. A crow cawed, then another and another. A grape vine kinked and curled upward beside a thick red cedar tree. Years before a hired hunter for a meager trading post whacked away the lower branches with a keen-edged ax, forming a hollow in the tree’s dead, lower branches.

Two steps…a pause…two steps…a pause… Canada geese ke-honked on the River Raisin, from the echoing sounds, beyond the lily-pad flats where the channel deepens. A crow cawed, then another and another. A grape vine kinked and curled upward beside a thick red cedar tree. Years before a hired hunter for a meager trading post whacked away the lower branches with a keen-edged ax, forming a hollow in the tree’s dead, lower branches. Msko-waagosh’s wigwam is down and the canvas packed away. On his jaunt the other night, he spotted a couple of trees suitable for two bents; he just needs to find a dozen or so more—all a bit stouter than the ones that deteriorated and broke. A different and distinct sleeveless waist coat looms on the horizon, but no rush there. Once he sees Mi-ki-naak’s new sash, I expect he will want one, too. While viewing photos, I discovered his dark brown sash is a shared accoutrement with the hired trading post hunter. This is a minor oversight on my part.

Msko-waagosh’s wigwam is down and the canvas packed away. On his jaunt the other night, he spotted a couple of trees suitable for two bents; he just needs to find a dozen or so more—all a bit stouter than the ones that deteriorated and broke. A different and distinct sleeveless waist coat looms on the horizon, but no rush there. Once he sees Mi-ki-naak’s new sash, I expect he will want one, too. While viewing photos, I discovered his dark brown sash is a shared accoutrement with the hired trading post hunter. This is a minor oversight on my part.