A downy woodpecker rapped three notes, “Tat-a-tat-a-tat.” Two followed, then three again, then two…

An unseen cardinal called to the east, off by the isthmus that divides the nasty thicket. “Tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu” was its four-note song. After a slight pause, the songbird’s melody moved south, but still four notes long…

Two Sandhill cranes passed overhead, just over tree-top high. The big wings swished and whooshed. The cranes chortled softly to each other as they flew on to the River Raisin, swollen beyond its banks from heavy spring rains. Perhaps those two spied the humble woodsman standing beside the young red oak tree, gazing upon the weathered wigwam?

“Kee-honk, kee-honk, yonk…” Goose music resonated through the river’s bottomlands and drifted into the hardwoods where the returned white captive stood. A mallard hen squawked, too, but for some reason its message did not fit the joyous chorus of the dawning.

“Kee-honk, kee-honk, yonk…” Goose music resonated through the river’s bottomlands and drifted into the hardwoods where the returned white captive stood. A mallard hen squawked, too, but for some reason its message did not fit the joyous chorus of the dawning.

“Tat-a-tat-a-tat-a-tat.” The woodpecker resumed its percussive search for a morning meal on a dead, barkless branch, in the direction of the big geese, at the edge of the woods, in the Year of our Lord, 1797.

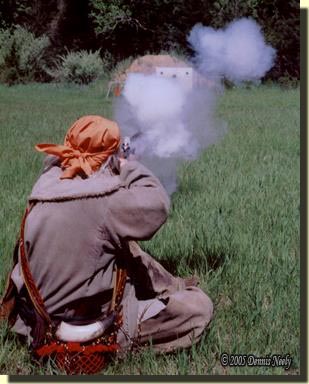

The time seemed right. The forest tenant placed the pe-be-gwun’s mouthpiece to his lips and offered a gentle, steady breath. A new melody, comprised of improvised notes, surrounded the wigwam. The woodsman mimicked the cadence and volume of the bird songs; he knew he could not duplicate their tone and did not try. Instead, Msko-waagosh concentrated on playing the mystic rhythm of the birds of the forest…

Pursuing a Specific Passage

In 2012, in those dismal November days after epizootic hemorrhagic disease decimated our whitetail herd, the persona of a returned native captive, Msko-waagosh, “Red Fox,” sprung to life. In the ensuing weeks and months, a fair amount of research time centered on the narratives of James Smith, Jonathan Alder and John Tanner. Most days, Native American flute music played in the background as I read and studied. For me, the instrument’s haunting tones sooth my soul, just as the simple sounds of the forest do.

One evening last summer I read a sentence from John Tanner’s narrative aloud to Tami. I was looking for something different, but as so often happens little gems pop up when a living historian least expects it. I knew the passage was there, I just hadn’t weighed its significance:

“I then dressed myself as handsomely as I could, and walked about the village, sometimes blowing the Pe-be-gwun, or flute…” (Tanner, 103)

She smiled and said, “Then Msko-waagosh ought to learn to play the flute.”

“It’s all I can do to get a proper note from a single wing bone turkey call,” or something close to that was my response as I put off her suggestion.

In the spring of 2001, flute maker and noted recording artist Tommy Lee helped Tami pick out her first Native American flute. He selected a dark-stained, 5-hole instrument from his display racks at the Dance for Mother Earth Powwow, held at Crisler Arena on the University of Michigan’s campus in Ann Arbor. The flute was tuned to the key of “G” in the minor pentatonic scale that typifies traditional Native American flutes.

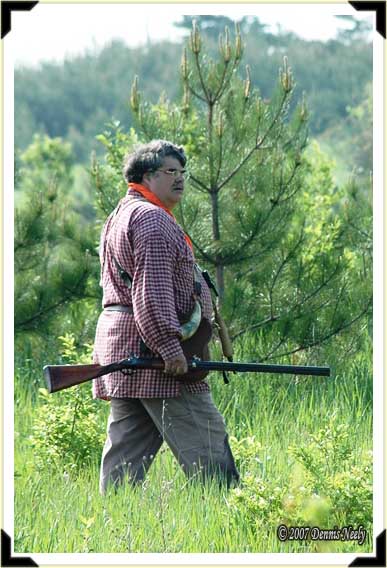

The flutes were always Tami’s bailiwick. She played; I listened and enjoyed. Tami has a “camp basket” made of woven vines, and when we pack for Friendship, an outdoor show, or a black powder shoot, one or more flutes find their way into the basket. When the spirit moves her, she sits and improvises on a flute.

The flutes were always Tami’s bailiwick. She played; I listened and enjoyed. Tami has a “camp basket” made of woven vines, and when we pack for Friendship, an outdoor show, or a black powder shoot, one or more flutes find their way into the basket. When the spirit moves her, she sits and improvises on a flute.

Over the years, we’ve come upon other Native American flutes, often in the strangest of locations. Tami always asks permission to play a flute offered for sale. On one such occasion, she tried several High Spirits flutes that were lined up in a glass display case in a small shop. An aromatic red cedar bass flute in the key of “Low D” offered forth unbelievable notes that filled the store with peace and tranquility. It had to come home with us, and it is one of her favorite love flutes.

On Friday evening at the Woods-N-Water News Outdoor Weekend, held in mid-September at the Eastern Michigan State Fair Grounds in Imlay City, Michigan, the show stays open until 9 pm. It was dark. Flickering candles and glowing lanterns lit the canvas tents in the primitive skills area as show guests thinned out.

Tami started playing the Tommy Lee flute at dusk while I spoke with guests. I sat down next to her about fifteen minutes before show closing. She paused, smiled and spoke of how busy the show had been. Then she reached into the vine basket, retrieved a flute and handed it to me. “John Tanner played the love flute, and you should learn.”

I enjoyed those minutes, enough so that I spent a couple of evenings watching how-to videos for playing the Native American flute. A common thread running through the instructions emphasized “playing from the heart.” A few weeks later a small, slim package arrived containing a used flute won in an online auction. This High Spirits Kestrel flute in the key of “High D,” is only 15 inches long, the perfect size to stash to the left of my work area.

Setting time aside to learn to use the wing bone call just never happened, until I placed the single bone among the pencils to the left of my keyboard. When I paused to think through a problem, I found myself picking up the wing bone and offering a few “clucks of advice.” I planned to do the same with the kestrel flute. To me, it doesn’t sound like this idea is working, but Tami says, “Your notes are improving.” I think she feels obligated to offer kind encouragement to a hopeless case—we’ll see…

Tanner’s life story was originally published in 1830. Native American words, in Tanner’s case a dialect of Ojibwe, were sounded out and written as they sounded. With that in mind, I consulted my copy of A Dictionary of the Ojibway Language by Frederic Baraga.

Bishop Baraga’s original work was published in 1853 and titled A Dictionary of the Otchipewa Language, which demonstrates the difference in spellings. The word he records for “flute” is “pi-pi-gwan,” sounding close to Tanner’s “pe-be-gwun,” the difference being common pronunciation from a given region (Baraga, 105). In addition, the current Ojibwe People’s Dictionary lists “bi-bi-gwan” as the word for a flute. Again, the variance of spelling is probably attributable to dialect.

The history of the flute is just as elusive as the proper pronunciation. Oral tradition versus a written history is part of the problem, at least when speaking of the Native American instrument. Flutes go back thousands of years, take many forms and appear in many world cultures. Most histories of the Native American flute pull up short at 1823, the date of acquisition of a wooden Native American flute collected by Giacomo Costantino Beltrami as he explored the headwaters of the Mississippi River. This flute appears to be the earliest known example attributable to Native American hands.

The Museum of the Ojibwe Culture in St. Ignace, Michigan, displays a small three-hole flute, or “whistle” as they label it, fashioned from a hollow bird bone. Ancient bone flutes existed in multiple cultures, and even today Native American performers use a small bone flute to imitate song birds within a musical score.

The Museum of the Ojibwe Culture in St. Ignace, Michigan, displays a small three-hole flute, or “whistle” as they label it, fashioned from a hollow bird bone. Ancient bone flutes existed in multiple cultures, and even today Native American performers use a small bone flute to imitate song birds within a musical score.

The noted ethnologist, Frances Densmore spent her entire life documenting Native American culture. Her first book, Chippewa Music, published in 1910 offered a detailed analysis of 200 Ojibwe songs. In 1929 she published Chippewa Customs, which dealt with all aspects of the Ojibwe culture.

Addressing the making of musical instruments, Densmore included a photograph of a six-hole Ojibwe flute made by Tom Skinaway complete with Skinaway’s instructions using his hand as a measuring device to locate the air chambers and sound holes. Unfortunately, Densmore did not list dates for the flute shown, her discussions with Tom Skinaway or Ojibwe flutes in general. (Densmore, 166-167)

If my chronology is correct, Tanner’s cited pe-be-gwun reference is from 1806. Thus, melding a Native American love flute into the portrayal of Msko-waagosh is period correct—using a modern flute is not, however. Several contemporary makers produce flutes similar to the one Skinaway made. I played a Butch Hall “G” minor flute made of aromatic red cedar that morning, which somewhat resembles Skinaway’s instrument.

It is conceivable a traditional black powder hunter might modify such a flute to imitate a century’s old instrument. The better course, and a key underlying premise to living history, is to follow Skinaway’s instructions and attempt to duplicate an Ojibwe flute such as Tanner might have used. As always, available time is the big obstacle, but the project is penciled on this living historian’s “to-do list…”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and my God bless you.