A Prologue

Dating passages in a hunter hero’s narrative is tricky. The stories sometimes are told out of order and/or without context. Thus, as living historians, we tend to focus on one sentence as our primary justification for including an item in our persona’s world without the proper backstory to flesh out the significance of those few words. Take, for example, this passage:

“I then dressed myself as handsomely as I could, and walked about the village, sometimes blowing the Pe-be-gwun, or flute…” (Tanner, 103)

If you will indulge me, dear reader, I would like to share a love story fit for the silver screen…

The Backstory…

“On going to Mouse River trading-house, I heard that some white people from the United States had been there to purchase some articles for the use of their party, then living at the Mandan village. I regretted that I had missed the opportunity of seeing them but as I had received the impression that they were to remain permanently there, I thought I would take some opportunity to visit them. I have since been informed that these white men were some of the party of Governor Clark and Captain Lewis, then on their way to the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Ocean.” (Ibid, 98)

Lewis and Clark wintered at the Mandan village from November 1804 to April 1805. Tanner goes on to say:

“Late in the fall [1805], we went to Ke-nu-kau-ne-she-way-bo-ant, where game was then plenty, and where we determined to spend the winter.” (Ibid)

Tanner then describes the types of gambling and games that were played. He relates one instance where his adoptive family lost a fair amount of property and how they won most of it back. Then a bet was placed:

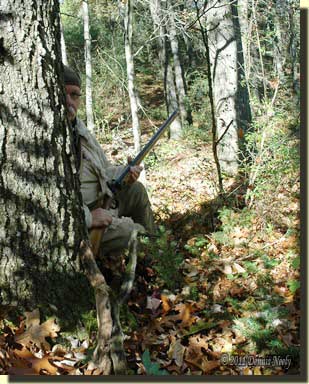

“We staked every thing we could command. They were loath to engage us, but could not decently decline. We fixed a mark at a distance of one hundred yards, and I shot first, placing my ball nearly in the center [Tanner usually hunted with a smoothbore]. Not one of either party came near me; of course I won, and we thus regained the greater part of what we had lost during the winter.” (Ibid, 100)

By this time, Tanner’s skill as a hunter and provider was known throughout the village, as was his marksmanship abilities. In 1806, Tanner was about 26 years old, single and…

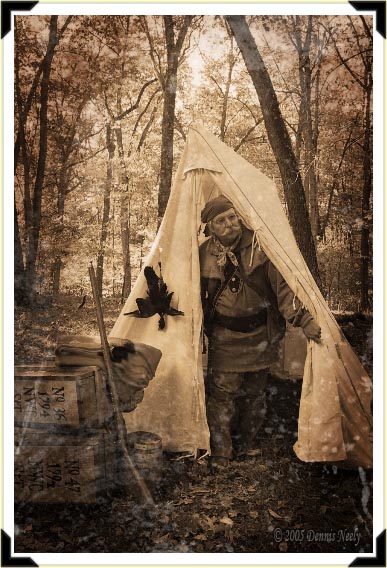

“Late in the spring, when we were nearly ready to leave Ke-nu-kau-ne-she-way-bo-ant, an old man, called O-zhusk-koo-koon, (the muskrat’s liver) a chief of the Me-tai, came to my lodge, bringing a young woman, his grand-daughter, together with the girl’s parents. This was a handsome young girl, not more than fifteen years old, but Net-no-kwa [Tanner’s adoptive mother] did not think favorably of her. She said to me, ‘My son, these people will not cease to trouble you if you remain here, and as this girl is by no means fit to become your wife, I advise you to take your gun and go away. Make a hunting camp at some distance, and to not return till they have time to see that you are decidedly disinclined to the match’…” (Ibid)

Time passes and the next scene begins to unfold:

“…I was standing by our lodge one evening, when I saw a good looking young woman walking about and smoking. She noticed me from time to time, and at last came up and asked me to smoke with her. I answered that I never smoked. ‘You do not wish to touch my pipe, for that reason you will not smoke with me.’ I took her pipe and smoked a little, though I had not been in the habit of smoking before. She remained some time, and talked with me, and I began to be pleased with her. After this we saw each other often, and I became gradually attached to her…” (Ibid, 101)

“…our acquaintance was not after the usual manner of the Indians. Among them it most commonly happens, even when a young man marries a woman of his own band, he has previously had no personal acquaintance with her…it is probable they have never spoken together. The match is agreed on by the old people, and when their intention is made known to the young people, they commonly find, in themselves, no objection to the arrangement, as they know, should it prove disagreeable mutually, or to either party, it can at any time be broken off.” (Ibid)

“My conversations with Mis-kwa-bun-o-kwa (the red sky of the morning), for such was the name of the woman who offered me her pipe, was soon noised about the village…” (Ibid)

Tanner’s scandalous actions brought the return of the old matchmaker, Muskrat’s Liver:

“…Old O-zhusk-koo-koon came one day to our lodge, leading by the hand another of his numerous grand-daughters. ‘This,’ said he to Net-no-kwa, ‘is the handsomest and the best of all my descendants. I come to offer her to your son.’ So saying, he left her in the lodge and went away. This young woman was one Net-no-kwa had always treated with unusual kindness, and she was considered one of the most desirable in the band. The old woman was now somewhat embarrassed, but at length she found an opportunity to say to me, ‘My son, this girl which O-zhusk-koo-koon offers you is handsome, and she is good, but you must not marry her for she has that about her which will, in less than a year, bring her to her grave. It is necessary that you should have a woman who is strong and free of any disease. Let us, therefore, make this young woman a handsome present, for she deserves well at our hands, and send her back to her father’…Less than a year afterwards, according to the old woman’s prediction, she died.” (Ibid, 101-102)

Tanner’s narrative cites several instances where illness and disease plague the village, and in one instance, he became very ill. By his telling, he was unconscious for several days and the disease left him nearly deaf. This disease had a variety of similar serious effects on others in the village who came down with it. But let us return to the backstory of this one passage…

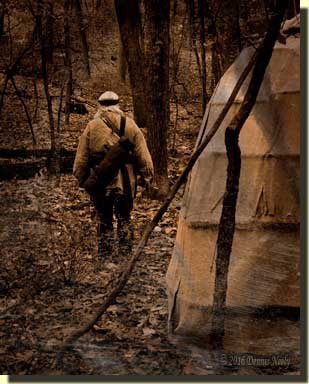

“…Mis-kwa-bun-o-kwa and myself were becoming more and more intimate…after spending, for the first time, a considerable part of the night with my mistress, I crept into the lodge [Net-no-kwa’s lodge] at a late hour and went to sleep. A smart rapping on my naked feet waked me at the first appearance of dawn on the following morning. ‘Up,’ said the old woman, who stood by me with a stick in her hand, ‘up, young man, you who are about to take yourself a wife, up and start after game. It will raise you more in the estimation of the woman you would marry to see you bring home a load of meat early in the morning than to see you dressed ever so gaily, standing about the village after the hunters are all gone out.’ I could make her no answer, but putting on my moccasins, took my gun and went out. Returning before noon, with as heavy a load of fat moose meat as I could carry, threw it down before Net-no-kwa, and with a harsh tone of voice said to her, ‘Here, old woman, is what you called for in the morning’…” (Ibid, 102)

Now the Passage…

“I now redoubled my diligence in hunting, and commonly came home with meat in the early part of the day, at least before night. I then dressed myself as handsomely as I could and walked about the village, sometimes blowing the Pe-be-gwun, or flute. For some time Mis-kwa-bun-o-kwa pretended she was not willing to marry me, and it was not, perhaps, until she perceived some abatement of ardour on my part, that she laid this affected coyness entirely aside.” (Ibid, 102-103)

And Then…

So we have this single passage that tweaked my interest a number of years ago. There is, of course, much to say about adding a Pe-be-gwun to a returned white captive’s portrayal. The primary documentation stares us square in the face. But again, as a living historian, a better understanding of the context of a passage sometimes includes a deeper look at what happens after…

“About this time I had occasion to go to the trading-house on Red River, and I started in company with a half breed belonging to that establishment, who was mounted on a fleet horse. The distance we had to travel has since been called, by the English settlers, seventy miles. We rode and went on foot by turns, and the one who was on foot kept hold of the horse’s tail and ran. We passed over the whole distance in one day. In returning, I was by myself and without a horse, and I made an effort, intending, if possible, to accomplish the same journey in one day; but darkness, and excessive fatigue, compelled me to stop when I was within about ten miles of home…” (Ibid)

“When I arrived at our lodge, on the following day, I saw Mis-kwa-bun-o-kwa sitting in my place. As I stopped at the door of the lodge, and hesitated to enter, she hung down her head, but Net-no-kwa greeted me in a tone somewhat harsher than was common for her to use to me. ‘Will you turn back from the door of the lodge, and put this young woman to shame, who is in all respects better than you are? This affair has been on your seeking, and not on mine or hers…now you would turn on her, and make her appear like one who has attempted to thrust herself in your way.’ (Ibid)

“I went in and sat down by the side of Mis-kwa-bun-o-kwa, and thus we became man and wife. Old Net-no-kwa had, while I was absent at Red River, without my knowledge or consent, made her bargain with the parents of the young woman and brought her home, rightly supposing that it would be no difficult matter to reconcile me to the measure… (Ibid, 104)

Like our own lives, a colorful backstory exists; then there is the present moment; and beyond these few heartbeats there are rewards and/or consequences—the pleasant and the unpleasant of life. Thus, there is more to understanding what it was like to live, hunt and survive in the Old Northwest Territory than plucking a few choice words from within one sentence. But more on that next time…

Experience the whole texture of the past, be safe and may God bless you.