Damp, melting snow pitter patted. The constant dripping sounded like a slow, steady drizzle. Hardwoods populate the lower two-thirds of the west slope of the long ridge. An unusual abundance of brown leaves remained on the branches and twigs. White coated each leaf. Now and then a gentle gust increased the intensity of the drips. An occasional glob of snow cascaded through a cedar tree’s lower limbs and dissipated into a fine mist before striking the ground.

At first light a younger deer’s squeaky bleat wove its way through the pitter patters. The sound came from the northwest side of the huckleberry swamp, about where I unleashed the death sphere on the broken-beamed buck two winters prior. The call was not “beeping,” as young does do when they are ready to breed but cannot find a mate, but rather a distressed blat.

This deer moved to the east and called three times at the leaning oak by the standing water. A solid, heavy-throated bleat answered from the snow-covered bushes in the swamp. The hillside returned to the quiet dripping of melted snow. A few crows cawed out by the river, and at one point it sounded like a full-fledged melee was about to break out, but that too sputtered into oblivion.

My lead holder scribbled on a journal page:

“…it is odd to see so many green leaves covered with snow. The mild fall, the lack of frost and the cool, but not cold nights, allowed the oaks to keep their leaves well into November. The understory, which is mostly autumn olive, is still green. Strange, but appreciated…”

A fox squirrel chirped in a cedar tree. Then, to my right, a black squirrel’s head popped from behind a red oak, not thirty paces distant. And down the slope, by a fallen poplar tree, a gray squirrel dug in the snow. That critter bounded to a large oak, scampered up the trunk, turned about and looked to the north. In due time, this little bundle of energy hiked its way up the tree, paused by the long gray scar of a dislodged limb, then perched at the crotch of the next branch.

A fox squirrel chirped in a cedar tree. Then, to my right, a black squirrel’s head popped from behind a red oak, not thirty paces distant. And down the slope, by a fallen poplar tree, a gray squirrel dug in the snow. That critter bounded to a large oak, scampered up the trunk, turned about and looked to the north. In due time, this little bundle of energy hiked its way up the tree, paused by the long gray scar of a dislodged limb, then perched at the crotch of the next branch.

A tingly right leg necessitated a rump’s readjustment on the wool bedroll. In the midst of a twist to the left, a deer’s ear flicked front-to-back as a brown, antlerless head rose above the snowy crest of the next rise to the south. The deer ambled on, abiding by no trail in particular. When it reached the top of the little knoll, it pawed the ground and nuzzled about some. After looking down the slope, the young button buck moved on with the faint southwest breeze crossing over its hind quarter and up the hill to the makeshift lair amongst four close-growing cedar trees.

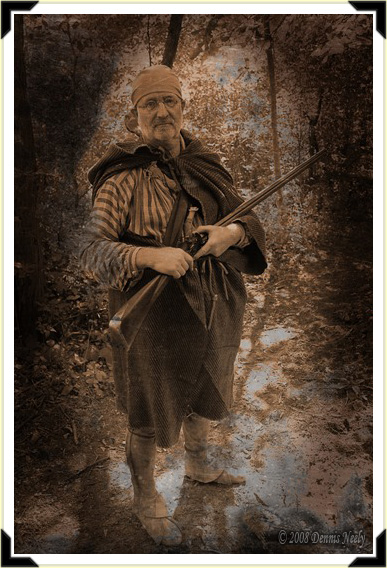

A Northwest trade gun, bruised from years of faithful service, rested across a returned captive’s wool-clad legs with the lock and butt stock area tucked under the folds of a thick trade blanket. There was no need for the hunter’s prayer, no utterance of “A clean kill, or a clean miss…” Instead, this innocent tenant of the forest, so unaware of the death messenger’s humble presence, plodded on. As he passed, not twenty paces distant, the infant stag obsessed with checking downhill; never once did he look to the ridge.

To the north, at the red oak that hid the black squirrel, this young buck glanced uphill for the first time. Perhaps it sensed the existence of a benevolent spirit, an older woodsman, captured in his youth, raised and mentored by his adopted Ojibwe parents, who did not need its tender flesh for subsistence. Regardless, the deer meandered on and soon disappeared from sight…

Passing on 18th-Century Shots

Perhaps I, too, do not glance “uphill” as much as I should, in a manner of speaking. Not long ago I retold the tale of passing on two first-year bucks one Sunday morning in mid-December. The year was 1796. The six-point trailed the seven-point. Neither had an inkling danger lurked so close. The pair offered multiple opportunities to accept the death sphere’s fatal message.

I commented on how blessed those two young bucks were to venture by at the wrong time (well, the right time in their lives). I had ten minutes to walk out, make it home and get ready for 11 o’clock church. Once they angled down the slope and started concentrating on the trail that crossed the big swamp, I slipped away.

Now regardless of my reason for leaving in the midst of an 18th-century adventure, the serious chastising that I received added a listener’s perspective to that story. As a result of that individual’s remarks, I think before I repeat the tale of “the blessed bucks,” and that bothers me. The gentleman was dead serious when he stated that I should have killed one or both. I guess he thought I could reload faster than I can. He went on to belittle my writing, then stated “You don’t kill enough game to make hunting with an old-style muzzleloader worthwhile…”

His rant continued, and when it died down I simply answered, “The gun and clothing made no difference. If I had my old, scoped Ithaca Deerslayer, I would not have shot at either buck or the two does that stood to my left. I’ve been passing on deer for thirty years and I’ll continue to do so.”

Over the years, a couple of outdoor writers have gotten after me for not following the “hook and bullet” formula for outdoor writing: the readers always want the writer to tell them about the game they took or the fish they caught. They have little interest in reading about the one that got away, or so the theory goes. There are exceptions, but take a gander at today’s outdoor media and see how many stories you find that fit the later mold—there aren’t many.

And for me, that is exactly the point of my scribblings. I have written many times about how disillusioned I became as a young hunter, because I couldn’t afford the firearm used, couldn’t travel to Valhalla and never saw the “thirty-point buck.” Thus, I make a conscious choice to recount the adventures where none of that happens. Besides, the story from the day before is almost always more of an adventure than the one leading up to the demise of a whitetail.

Among hunters, the common question after the season closes is: “Did you get a deer?” My “no” answer has evolved into, “I had a good season, but I didn’t see a deer I wanted to kill.” It still comes down to a “no,” but a qualified “no,” at least to my way of thinking.

When the kids were still at home, I worked hard to fill my tags with good-sized deer—165 pounds dressed or larger. That meant shooting mature bucks, preferably earlier in the season when body mass is higher. Antler size, being indicative of maturity, helped guide the selection. I doubt either of the blessed bucks would have field dressed out at 120 pounds. After de-boning that’s not a lot of meat for the freezer. One might say I’m a choosy shopper at the wilderness grocery store.

Unfortunately, the epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) outbreak in 2012 wiped out most of our deer herd. Taking a doe is still not a good option, but the herd numbers are rebounding. EHD removed the mentors from the flock, thus the survivors’ habits do not mirror those of the deer pre-EHD. The young bucks of that season went 100-percent nocturnal, and now that they are the sires of the herd, they are even more cautious about being out and about during daylight hours.

Prior to 2012, the mature bucks sometimes moved around mid-day. That was the best time to put meat in the freezer, but that practice no longer works. I saw four bucks all season, the blessed bucks, a first-year buck the second evening of the season, and a good-sized, broken-rack buck that came over the ridge from the river bottom five minutes after shooting hours ended.

Given my criteria, the opportunities simply were not there this year. We are not going to starve, and I will not kill an animal just to produce a story that fits someone else’s writing guidelines. I don’t need to, because I came away with quite a few memorable 18th-century tales—a new one almost every outing.

Given my criteria, the opportunities simply were not there this year. We are not going to starve, and I will not kill an animal just to produce a story that fits someone else’s writing guidelines. I don’t need to, because I came away with quite a few memorable 18th-century tales—a new one almost every outing.

One of the highlights was a frantic doe that ran by and knocked dead branches off the boxelder I was sitting at. A gun-barrel-sized branch came to rest in my lap and another grazed my cheek. She was two trade-gun lengths away when she passed. She halted her course about thirty paces crosswind, and offered an easy shot John Tanner would have taken.

On another occasion, a doe walked upwind of me, maybe seven paces distant. Like the button buck, she never glanced my way. And again, in the midst of a still-hunt, I had two does come right at me. I was treed at the time. They veered to the south, not fifteen paces out, stopped and looked back to the knob they just crossed over. I thought for sure a buck was behind them, but none arrived. John Tanner would have killed either one of them, and I could have, too.

I had a great season, even if I didn’t take a shot or put venison in the freezer. As I tried to explain to the gentleman, I journeyed back in time and saw white-tailed deer, even if there was no need for the hunter’s prayer.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.