-

Recent Posts

Categories

Archives

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

Blogroll

Forums

General Living History

Historical Sites

Organizations

Artists

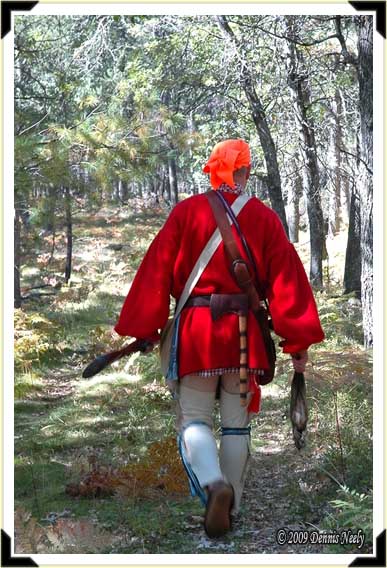

“Morning’s End”

Posted in Snapshot Saturday, Squirrel Hunts

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

1 Comment

MacMillan’s Cove Revisited…

A Brief Introduction:

The Lost Word Writers Group’s annual Halloween “open microphone night” is tonight at the Carnegie Branch of the Jackson District Library. All genres are represented, but as one might expect, horror writing rules the evening.

The LWWG is blessed with many talented writers and authors who publish their works in print and online venues both here and abroad. For some strange reason a good percentage of our writers dabble in the macabre, and are they good at it. Two long-standing members of our group are affectionately dubbed the “Heroes of Horror:” Devlin Giroux and T. G. Reaper. “Reaper,” as we call him, has made Amazon’s Best Seller List.

Well, I have endured my share of good-natured coaxing and a bit of threatening from certain “un-named writers” in the group. In the fall of 2014, I broke down and tried my hand at horror fiction. Cindy, Autumn, Devlin and the Reaper encouraged me to post the piece on this blog at Halloween. With our reading tonight, I thought I would once again share this gory 18th-century, backwoods tale, set on the banks of the River Raisin in the Old Northwest Territory. Read on if you dare…

MacMillan’s Cove

Drips fell from the ash paddle’s blade. The paddle dipped and pulled, then hooked outward in one fluid motion. Crimson maple leaves swirled in the River Raisin’s cool, fishy-smelling water. Dip…pull…hook…dip…pull…hook. The linen and leather clad wanderer rested the paddle across the gunwales. The wooden bateau drifted in the gentle current. Out of caution, the hunter’s right hand gripped the Northwest gun’s forestock as the little vessel eased around the river’s bend.

Not far ahead, before the river’s next turn, David MacMillan spotted a small sandy cove where a wooded hillside touched the Raisin’s clear waters. The tiny hollow appeared pleasant and inviting and out of place, not at all swampy like the mucky, treacherous cut banks that lined this stretch of the winding river.

The sun touched the western tree tops; the brown-painted bow nudged the yellow sand. Smooth-bored trade gun in hand, the woodsman pulled the bateau ashore. Muzzle up, firelock ready, he crept to the edge of the hardwoods. Overhead a solitary crow cawed, refusing to fly away at the intruder’s advance.

The sun touched the western tree tops; the brown-painted bow nudged the yellow sand. Smooth-bored trade gun in hand, the woodsman pulled the bateau ashore. Muzzle up, firelock ready, he crept to the edge of the hardwoods. Overhead a solitary crow cawed, refusing to fly away at the intruder’s advance.

A short circular stalk through the bright-colored oaks, hickories and maples assured MacMillan he was alone. Returning to the shore, the hunter grabbed the hand-forged ring secured to the stem and dragged the bateau up on the sand. He pulled back the weathered tarp and began unloading the five sacks of wild rice and a pack of half-dressed deer hides destined for the trading post at Frenchtown, two hard day’s journey downriver.

Humming an old Irish ditty, MacMillan rolled the bateau over and rested a gunwale on the stacked sacks and bale. He threw the tarp over the vessel and its cargo, creating the night’s temporary shelter. With the Northwest gun’s barrel leaning against the humble abode, the cheerful woodsman dropped to his knees and set about digging a fire pit in the sand. The crow cawed three times, then flew to the east.

That night in mid-October, in the Year of our Lord, 1795, deep in the Old Northwest Territory’s backcountry, gold and orange and lavender clouds highlighted the end of a weary day. Still humming, MacMillan roasted a hand-sized chunk of venison haunch, skewered on a fresh-whittled witch-hazel branch, over the fire’s glowing coals. As the meat cooked, he’d carve off a slice with his butcher knife, then return the venison to the fire.

A thump out on the river brought MacMillan to his feet. The smoothbore’s muzzle swung to the origin of the sound; an uneasy thumb twitched as it pressed against the half-cocked hammer. A birch bark canoe slipped into the reach of the fire’s dancing light.

“I mean you no harm,” a gruff voice said from the darkness.

“Who are you, and state your business,” MacMillan asked.

“Joseph Lewis, a hunter and scout.”

“Well, come ashore. I suppose you’re looking to spend the night?”

“I’d share your fire,” Lewis said.

“There’s some venison left, if you like,” MacMillan said, as he took measure of the man standing before him.

Lewis volunteered little as he sat across from MacMillan and roasted a hunk of venison. He smiled now and then. He looked up and spoke of the beauty of the evening, commenting on the shimmering stars in the now cloudless heaven and the rising moon. The scruffy-looking visitor asked about the deer farther upriver, the number of hunters in the backcountry and if there were any Ojibwe or Pottawatomi camps in the area.

MacMillan obliged with a minimal report, noting this was his first season on the River Raisin. As was their habit, both men retired with their guns tucked in their wool blankets: MacMillan under his bateau and Lewis in the open on the opposite side of the fire.

A little past midnight, MacMillan roused and rolled onto his right side. Orange embers pulsated in the fire pit, bathing the sandy cove in a blood-red light. The woodsman’s eyelids grew heavy. When he awoke again, an Ojibwe warrior sat cross-legged, staring into the coals. He was stripped naked, except for his moccasins and breechclout and his face and upper body were painted black, the sign of death.

A little past midnight, MacMillan roused and rolled onto his right side. Orange embers pulsated in the fire pit, bathing the sandy cove in a blood-red light. The woodsman’s eyelids grew heavy. When he awoke again, an Ojibwe warrior sat cross-legged, staring into the coals. He was stripped naked, except for his moccasins and breechclout and his face and upper body were painted black, the sign of death.

Under his four-point blanket, the woodsman’s hand slipped along the Northwest gun’s forestock. The veins in his neck throbbed; he fought to control his breathing. He pretended he was still asleep. His mind racing, MacMillan played out how he might warn Lewis. Then he realized another warrior, faint and ghost-like, slept in a tattered blanket beside Lewis.

As MacMillan tried to make sense of the perilous circumstance, the Ojibwe warrior took a pinch of tobacco from a leather pouch. The offering flamed up when he sprinkled it on the coals. He then stood, faced the bateau shelter and raised his hand, palm open. With his fingers spread wide, he moved his hand slow from west to east, then east to west as he spoke in his native tongue.

At the end of this incantation, the warrior’s black eyes pierced the innermost depths of MacMillan’s soul. Within the warmth of this wool blanket, he felt his skin grow as cold as if he had broken through the river’s January ice. In an instant, the calm night air smelled of strong tobacco mixed with the stench of putrid flesh. Uncontrollable shivers rippled up and down his spine, and it was then that the woodsman discovered his hand could no longer move, he could no longer move.

The Ojibwe turned back to the fire, pulled his tomahawk from the back of the sash that girdled his waist and held it aloft with both hands. The chanted syllables echoed in the hardwoods. MacMillan wondered why Lewis did not spring to his feet. At the end of the somber song, the warrior lowered the tomahawk, walked to the sleeping Indian and straddled his body.

The black, piercing eyes glanced straight at MacMillan. With a war hoop and a swift, downward blow, the warrior buried the tomahawk in the sleeping Indian’s right temple. The blow made no sound. The body did not move or jerk or convulse. There was no blood. The assailant left the tomahawk where it was with the maple handle angling up.

“For God’s sake, do something, Lewis!” The scream echoed in MacMillan’s mind, but his lips didn’t, couldn’t move. “Lewis! Lewis! For God’s sake, wake up Lewis!”

The Ojibwe returned to the bateau shelter, reached down and grasped the handle of MacMillan’s trade ax. MacMillan felt the ax’s handle slip from his belt. Again the warrior turned to the fire and raised the ax aloft, suspended horizontal between both hands. The chanted lyrics were the same, the tones just as somber, just as foreboding, just as unforgettable.

The mystic demon grasped the ax’s hickory haft in his right hand. MacMillan glanced across the fire pit. The sleeping Indian, the tomahawk, the blanket, all were gone, the sand undisturbed. The Ojibwe walked to Lewis, who faced away from the fire, and straddled the hunter’s body. This time, when the warrior looked at MacMillan the hint of a smirky, sly smile appeared.

As the ax rose above the Ojibwe’s head he let out the hideous war hoop. The blow came quick. The ax buried deep in Lewis’ temple with a squishy, snapping, sickening thud that sounded like the time MacMillan’s older sister beat on a ripe pumpkin in a fit of rage. Blood gushed and splattered. The scout’s gray blanket shook and flailed with the involuntary thrashings of a not-yet dead man. Dark red rivulets trickled through Lewis’ auburn hair. The ax handle angled up, but it shook and twitched and quaked in the fire’s orange glow.

* * *

“Get up, you scoundrel, get up, I say!” David MacMillan’s head pounded as it once did after a night of drunken revelry at Christina’s Tavern. He opened his eyes. The muzzle of a Brown Bess musket lurked a few inches from his nose. “Get up, get on your feet,” the orders came as a hand pulled back the tarp, opened his blanket and snatched away his Northwest gun.

The woodsman crawled from under the bateau and rose to his feet. On the other side of the fire pit, three British rangers stood over the lifeless body of Joseph Lewis, the company’s seasoned wilderness scout and the captain’s only brother.

“I didn’t…I can…you don’t…” With each attempt, MacMillan comprehended the futility of his explanation. Captain Lewis felt the front of the pockets of the woodsman’s blue wool weskit. His fingers probed the right pocket and retrieved a gold watch MacMillan had never seen before.

“That’s Joseph’s watch,” one of the rangers said in an agitated tone. “Check his other pocket, captain.”

“Father’s tin snuff box!” Captain Lewis’ voice could not hide his revulsion and disdain.

“What is your name?”

“David MacMillan, sir.”

“Where is your ax?”

MacMillan did not answer. To his right, a hollow, muffled, scraping bone-on-wrought-iron sound hung in the air. A ranger of slim build stood to the left of Captain Lewis and confronted the accused with the bloodied ax. “Is this your ax?”

“There is nothing that I can say that will convince you otherwise,” MacMillan whispered.

“Tell us all of it,” Captain Lewis demanded. At which point David MacMillan related the entire unbelievable incident.

“That is nothing more than the old Ojibwe tale that is told about this cove. It is pure nonsense.” Grabbing MacMillan’s left arm, Captain Lewis yanked him around and gave him a shove in the direction of the rangers’ canoes. “You’ll hang at Fort Detroit. Bind him and get him out of my sight.” A ranger took MacMillan’s right arm and started to lead him to the canoes.

“No!” Captain Lewis shouted too late. Wielded by the angry ranger that confronted the supposed killer, MacMillan’s own ax struck him square in the left temple. His body went limp and crumpled to the ground. Blood oozed from the haft-deep wound as the unfortunate woodsman began to shake and tremble as poor Lewis had in the night…

* * *

MacMillan felt no pain, no trickles from his scalp, no involuntary movement. To the contrary, his body felt light and airy as if it was floating next to his bateau shelter. He saw the seven rangers arguing with the captain over the unfortunate display of wilderness justice.

Then, two birch bark canoes came around the north bend in the River Raisin. One carried an old Ojibwe woman dressed in her finery, paddled by an old warrior of elegant stature. The second held a younger Indian woman and three children. The Ojibwe warrior who killed Lewis suddenly appeared by the fire pit. He, too, was dressed in fine clothing with much trade silver.

The canoes beached and a great reunion began, just to the north of Lewis’ body. The rangers seemed oblivious. The Ojibwe warrior walked to the fire pit with his pipe bag cradled in his left arm. He filled the pipe’s bowl with tobacco, then sprinkled a few pinches on the last of the fire as he spoke.

The tobacco flared up with a roiling puff of white smoke. He bent down, picked up an ember and placed it in the pipe’s bowl. The Ojibwe took two puffs then handed the pipe to his father who held it aloft with both hands, spoke in a reverent tone and then smoked.

Then the warrior turned to his right and offered the pipe to MacMillan. Displaying a bit of apprehension, the now-dead woodsman touched the pipe, reasoning it was not real. Finding otherwise, he took it to his lips, puffed twice and handed it back. The warrior smile and spoke to him in his native language, but MacMillan heard his words in English.

“I can go now,” the Ojibwe said, “and you are to take my place, until a suitable replacement should happen to camp at this cove and relieve you.” Having said that the warrior knelt in the stern of his family’s canoe and paddled out into the River Raisin’s narrow channel. Partway to the north bend, both canoes vanished. In time, Captain Lewis’ British rangers buried MacMillan’s body where it fell, loaded his packs in his bateau and departed.

Years passed, settlers arrived, and a town flourished a ways beyond the north bend. The legend grew, and to this day, stories abound about the spirit of the murderer who wanders about the sandy hollow where the wooded hillside touches the River Raisin—a place called MacMillan’s Cove.

Beware of MacMillan’s Cove, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in General, Worth thinking about...

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on MacMillan’s Cove Revisited…

“Time Travel Mishap”

“Snapshot Saturday”

Posted in Hunting Camps, Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

2 Comments

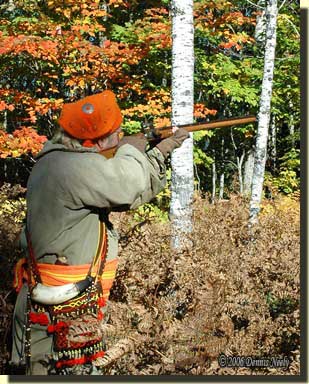

A Hunter Orange Missive

A week or so ago James, a loyal reader from Georgia, sent an email asking “How do you meet the requirements for the blaze orange that you are supposed to wear?”

What a great question! This topic comes up all the time at the outdoor shows, and I have hunter orange clothing examples on hand and photos in the albums to show guests the many ways a traditional hunter can comply with the law. Over the years I have written a number of magazine articles on the subject, and when his request came in I started looking through this site with the idea of sending him a link to one or more posts. Well there aren’t any, grumble, grumble, grumble…

Yes, I talk about using hunter orange in the various posted articles, the latest one being “A Circuitous Still-Hunt.” But I have not addressed the topic, and due to the serious safety considerations associated with today’s hunting environment, I thought it was time to correct that oversight on my part.

Yes, I talk about using hunter orange in the various posted articles, the latest one being “A Circuitous Still-Hunt.” But I have not addressed the topic, and due to the serious safety considerations associated with today’s hunting environment, I thought it was time to correct that oversight on my part.

I thought it best to elevate “An Atrocious Fashion Sense?” to full page status, so I placed this missive under “The Basics” category in the navigation bar. Please let me know what you think, and how you comply with hunter orange regulations.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Clothing & Accoutrements, Safety

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on A Hunter Orange Missive

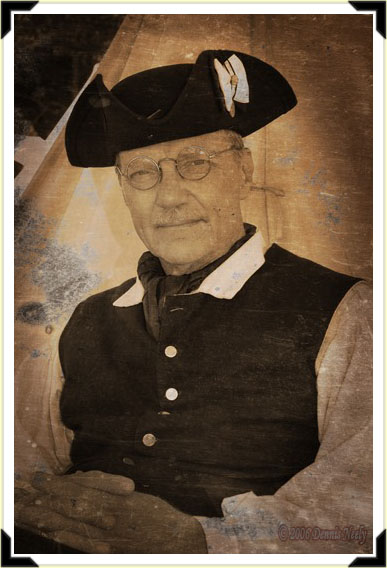

“I’m a Mountain Man”

“Snapshot Saturday”

“I’m a mountainman, born and bred…” Ron LaClair, one of the most dynamic traditional black powder hunters one could ever hope to share a camp with. He recited this poem around the evening fire at Swamp Hollow in 1835…

Posted in Persona, Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

1 Comment

A Circuitous Still-Hunt

Inner voices suggested a different course. Trail-worn elk moccasins turned about and struck off in the opposite direction. This new still-hunt progressed over the rise and down into a small valley. The depression’s south end spilled into a dense, difficult-to-navigate thicket: little brush-covered islands the size of a half-grown heifer interspersed with standing water and fallen trees.

The trail that followed the edge of this thicket circled up the hill to the west, passing downwind of a large white oak that met its demise perhaps five years earlier. This unfortunate hulk lay sprawled upon the hill’s crest, having fallen to the north. Purple raspberry switches entwined with broken limbs and branches. Near the tree’s top, a thin strip of leaf-covered ground led through the wreckage to the white oak’s main fork. The left moccasin cleared the leaves away; the blanket roll eased into the secluded nest.

In the fall of that year, 1796, wild turkeys frequented that doe trail, both morning and evening. Sunlight reflected off the sleeves and collar of my white ruffled shirt, but was of little consequence. Sequestered within that lair, only my nose, eyes and long gray hair remained visible to passersby. If the opportunity arose, the death bees would swarm before a turkey’s wary eye detected the ruse.

But that morning remained quiet, the change in direction proved unproductive. With the sun creeping higher, I reached in the pocket of my wool, sleeveless waistcoat and retrieved an orange silk scarf. The scarf was wadded, but already rolled tight and tied. All I had to do was unwrap it, adjust my hair and pull it down in place, just above my ears. “Now you are chasing squirrels,” the historical me whispered.

But that morning remained quiet, the change in direction proved unproductive. With the sun creeping higher, I reached in the pocket of my wool, sleeveless waistcoat and retrieved an orange silk scarf. The scarf was wadded, but already rolled tight and tied. All I had to do was unwrap it, adjust my hair and pull it down in place, just above my ears. “Now you are chasing squirrels,” the historical me whispered.

I leaned the Northwest gun against the main limb, pushed up on my knees and slung the portage collar’s leather brow band over my shoulders. The bedroll settled against my back, a bit lower than normal—the collar’s long straps, wound several times around the rolled blanket, stretched a bit during the still-hunt that brought me to the oak fortress.

With the smoothbore cradled, my right shoulder pressed against a limb that angled up. A long, cautious pause produced ample time to survey the glade. A couple of blue jays swooped close, but held their tongues. Sparrows flitted and chipped. One bounded up and down on a raspberry switch, not two trade-gun-lengths distant. Satisfied, elk moccasins struck off on the next arc of the circuitous still-hunt that eventually returned to the brush shelter in the hollow…

A Chance Discovery

Changing direction sometimes produces miraculous results, but not on this particular traditional black powder hunt. Sometimes it pays to listen to an inner voice and sometimes it doesn’t. But from the traditional woodsman’s perspective, the point is to be ever vigilant, just as the critters of the forest are ever on alert. On occasion, changing direction, or at the least being vigilant for opportunities a new path offers, has proved beneficial and rewarding.

I recently attended the Indian Art & Frontier Antiques Show, held at the Washtenaw Farm Council fairgrounds, 5505 Ann Arbor-Saline Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Last year there were a number of original Northwest guns on hand, and I was hoping to see them again. Well, that didn’t happen, and it never does when I plan ahead and have a list of questions.

But the surprise of the show was a half dozen compasses dating from the World War I era back to one that was dated “prior to 1850.” That compass in particular bore a striking resemblance to the one I carry and wrote about in “The Still-Hunt Back.”

But the surprise of the show was a half dozen compasses dating from the World War I era back to one that was dated “prior to 1850.” That compass in particular bore a striking resemblance to the one I carry and wrote about in “The Still-Hunt Back.”

Darrel Lang and I both examined this artifact and I took several photos. The compass wasn’t for sale, only display. We talked with the owner and asked questions. All he knew was what “a compass guy” told him. He had no maker’s name and we could find no maker’s mark. He was told it dated “prior to 1850,” but that was about all the information he had. “Prior to 1850” covers a lot of history, and certainly doesn’t place it in the 1790s, but it doesn’t rule it out, either.

The compass from the show looks identical to one shown in Neumann and Kravic’s Collector’s Illustrated Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, pg. 89, item 5, without the sundial “gnomon,” or fold-up vertical vane. Neumann and Kravic list the size as 2-1/4 inches by 5/8 inch and date the compass to “1750-1765.”

The reproduction compass from the 1980s on the left and the original compass made “prior to 1850” on the right

Comparing the original to the reproduction uncovered as many similarities as differences. Both are brass. When open they appear similar. I didn’t have any facility to weigh the original, but it felt much lighter that the reproduction which weighs 3 ounces. The difference is in the case construction. The brass used in the original is clearly thinner than that of the reproduction.

The case of the original measured 1-11/16 inch in diameter. We didn’t screw the top on to get an exact thickness, but it was close to 1/2 inch tall, give or take a frog hair. The reproduction case is 1-3/4 inch by 3/4 inch.

The lid of the original screws on; the fine threads can be seen in the upper photo. The reproduction’s lid slides over a lip. The same lip exists on the original, but with external threads. Other than two engraved lines, the two brass faces, or hour dials, bear a striking resemblance. What look like caricature legs with striped stockings are present on both, the original might have rudimentary “buckle shoes?” The sundial vane, or gnomon, was missing on the original, but the mounting stubs that remain are close in size and shape to those of the reproduction.

The needles are different, the original looks like a sword, rather than a flat bar. Both are blued and have a brass “balance” point in the center. If I read it right, the “T” that forms the handle marked magnetic north.

The paper faces are different, yet similar. They both have an eight-pointed star about the center, the points alternating red and blue in color. The original has an additional eight small points in black and white for the intermediate directions. The reproduction’s star is larger and the abbreviations for the directions face the center, outlined within two concentric circles. The original appeared to have hand-lettered initials, resting above lines perpendicular to the center, with more directions present. There is a distinct variation to the letters, which supports the hand-lettered notion, but I have no idea how the maker could print so small.

The outer cases are similar, yet different, too. The original sports engraved circles on both the top and bottom. The top has three lightly engraved circles at the outer edge. The bottom had three such circles plus two more close to the center, perhaps a half inch in diameter. The reproduction has no such ornamentation. The cases of both are tarnished and discolored from handling.

The outer cases are similar, yet different, too. The original sports engraved circles on both the top and bottom. The top has three lightly engraved circles at the outer edge. The bottom had three such circles plus two more close to the center, perhaps a half inch in diameter. The reproduction has no such ornamentation. The cases of both are tarnished and discolored from handling.

At best, the reproduction bears a “strong resemblance” to the original (assuming the artifact can be dated to the late 18th century). It is not an exact copy. If done properly, adding the engraved circles to the outer case would add to the historic impression. In my estimation, having an exact copy made would cost in excess of $100.00. For the number of times I use a compass, the $30 version is acceptable, at least for now.

So I didn’t come away from the Indian Art & Antiques Show with any great revelations about Northwest trade guns, at least not what I had hoped for. But by fostering a fertile mind, I came away with new knowledge on a number of fronts, including a better understanding of compasses.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Research, Squirrel Hunts, Turkey Hunts

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting

1 Comment

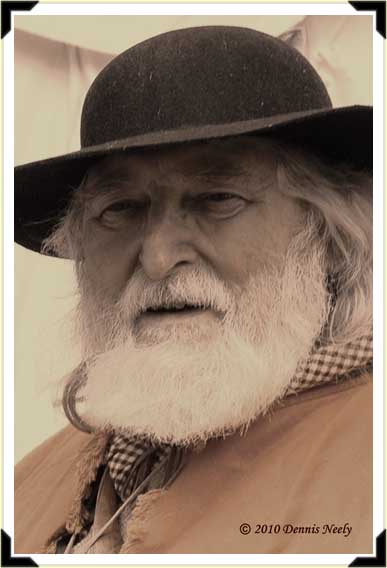

“James Moss of Clark’s Militia”

“Snapshot Saturday”

Posted in Scenarios, Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “James Moss of Clark’s Militia”

“Make it to the woods…”

Time slipped away this week, modern time that is. The same happened three weeks ago. Thoughts of grouse cartwheeling from a glorious cloud of white sulfurous stench oozed into oblivion with nary a flush, but perhaps with the utterance of a naughty word. Msko-waagosh would never do that, but I did.

The sear clicked. The tarnished brass butt plate slammed home. The grouse winged hard and was already beyond the Northwest gun’s effective distance. Onaway, Michigan.

The anticipation of the trip to Lake Gogebic in Michigan’s western Upper Peninsula exceeded the event, at least on the grouse hunting front. The correct 18th-century preparations make little difference if the “partridges” (the name my hunter heroes used to describe the ruffed grouse) don’t cross time’s threshold, too.

Grouse hunts aren’t that common for either of my personas; the last one was in late September of 2006, or I should say 1796, near Onaway, Michigan. The trading post hunter flushed eight or nine birds that day and got off two shots. A ruffed grouse is one of the few game birds or animals that “Old Turkey Feathers,” my Northwest trade gun, hasn’t brought to the family dinner table.

Several avid bird hunters told me how great the grouse hunting was in and around Lake Gogebic, which swelled my hopes. In his mind, my alter ego expected more flushes than in Onaway…

A Great MOWA Experience

Tami and I traveled to Lake Gogebic for the Michigan Outdoor Writers Association summer conference in mid-September. MOWA writers come together twice a year, and I had to miss the February meeting at the Ralph A. MacMullan Conference Center at Higgins Lake. When the dates were announced, a scheduling conflict put a dark cloud over this conference, too. Mark Sak and Tom Lounsbury kept pestering and finally convinced me I needed to attend. I’m glad I did. Thank you, fellas.

Tom Lounsbury—a good friend, radio host, and noted outdoor scribe—and I shared several grouse chases. We had a wonderful time. Tom Pink, a popular columnist with Michigan Outdoor News, joined us on Saturday, and the three of us enjoyed another great day afield. He hunted with a 12-gauge percussion double-barrel shotgun I brought along, just in case someone wanted to try hunting grouse with a black powder arm.

But MOWA conferences are more than hunting or fishing trips. Such outings offer a tremendous opportunity to learn, ponder circumstances and improve one’s writing and photography skills. We share breakfast, lunch and dinner and the pressing outdoor topics of the day are foremost in our discussions—along with some good-natured kidding. In the evenings, some pull up a chair and rehash the day’s doings.

At the summer conference, the Saturday night dinner ends with the presentation of the MOWA Excellence in Craft Awards. I was shocked, humbled and honored when my name was called, more than once. I was truly blessed, receiving four first place honors: the 2016 Cliff Ketcham Award: best hunting outdoor feature, a traditional black powder hunting story, “Fooling ‘Old Lady Gray’;” the James H. Hall Award: best outdoor feature highlighting non-hunting, a black powder shooting sports missive, “An afternoon African safari;” the James A. O. Crowe Award: best contribution as a columnist for the “Black Powder Shooting Sports” column published in Woods-N-Water News: Michigan’s Premier Outdoor Publication; and the Charlie Welch Award: best published black and white photo for “I have knives,” an image that appeared in the February 2015 issue of Muzzle Blasts: Official Publication of the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association.

MOWA was founded in 1944 and is a non-profit organization that includes outdoor writers, editors, photographers, broadcast journalists, lecturers and public relations specialists. MOWA members are dedicated to the preservation and conservation of the state’s natural resources and the practice of stewardship and good sportsmanship in outdoor recreation. Mort Neff, Ben East, Fred Bear, David Richey and Gordon Charles, to name a few, were all MOWA writers, as were the folks the awards are named after.

For me, one of the major takeaways from these awards is that the black powder shooting sports and traditional black powder hunting are relevant to Michigan readers, and that this handful of stories were judged by some of the best writers and editors in the country as being topnotch. I doff my headscarf in thanks to the many folks who take their valuable time to answer my questions and help me with the photos and quotes that accompany my scribblings. Thank you, all!

DennisNeely.com web site updates

Updating my author web site, dennisneely.com, has been on my “to-do list” for some time. However, life always seems to get in the way. At any rate, I’ve spent the last week and a half updating the site—spurred on by several conversations at the MOWA conference. There’s more to do. There always is…

The portfolio format is changed, and I’ve posted several of these award-winning articles. They are not new to regular readers of Woods-N-Water News, but I hope some might enjoy the feature stories.

In addition, I made a pledge to “make it to the woods every day in the month of October,” and I’ve only missed one day, and that was due to the wagon trails being too wet. I don’t need more property damage to repair.

And I’m down to sanding the stock of the Northwest gun that’s been lurking in the closet all these years, too. With any luck that smoothbore should be ready to shoot by the first of next week, then the final finishing can begin. To accomplish one project, others have to take a backseat, which is why I haven’t posted a new story to this site in the last two weeks. Dear reader, I trust you will bear with me…

Until then, make it to the woods, be safe and may God bless you.