Three hen turkeys walked north. Frost-covered leaves crackled with each footfall. The last bird, the largest, sounded like a white-tailed deer half-sneaking across the flat at the base of the hill, twenty-five paces distant. Brilliant spears of sunlight darted over the far eastern tree line and pierced the cedars and oaks on that calm, late-November morning in the Year of our Lord, 1796.

One bronze beauty paused near an open scrape. It stood stiff and erect, soaking up the rising sun’s warmth. Then, for no apparent reason, that wild turkey ran uphill, head down, neck straight out. Thirty paces hence, the bird slipped within a tight-packed stand of red cedar trees. The two remaining hens glanced at the escapee, then went back to pecking and scratching.

Lo, not two minutes later, the first bird came into sight, running as fast as before, through the scrape, under a leaning cedar and out to the four poplar trees where it joined the other young hen. The bigger turkey meandered on her way, a few trade-gun lengths to the east of the doe trail. In time, the trio wandered out of sight without so much as a hint of additional strangeness.

Two gray squirrels began searching for acorns at opposite ends of the flat. One ran along a dead trunk, spiraled around a powder-keg-sized oak sapling, then stopped to fling leaves and dirt in the direction of the scrape. The rummaging squirrel numbers grew to six, maybe seven.

A constant din of rustling leaves shrouded the hoof-falls of a scruffy button buck. A twitching ear-tip foretold of the forest tenants presence. This youngster angled southwest to northeast downhill. He sniffed the ground where his trail intersected the main doe path. Showing no undue concern, the little buck plodded along, stopping now and then to test the wind or gaze out to the big swamp.

The button buck avoided the scrape. The hair around his left shoulder displayed two hoof cuts from fighting. When he was about eighteen paces upwind of the downed oak top that hid my deadly being, a large doe appeared where I first glimpsed him. She showed more caution and a greater intensity for moving along.

The button buck avoided the scrape. The hair around his left shoulder displayed two hoof cuts from fighting. When he was about eighteen paces upwind of the downed oak top that hid my deadly being, a large doe appeared where I first glimpsed him. She showed more caution and a greater intensity for moving along.

The old doe soon caught up to the little buck. Along the path she kept staring back over her hind quarters and flipping her tail. She butted the youngster’s rump with her head, chased him to one side, and picked up her pace as she held to the trail.

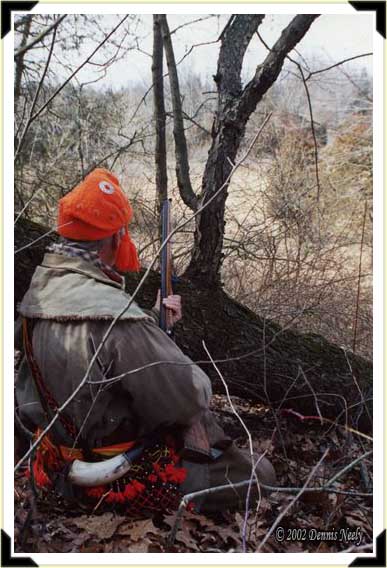

When the button buck looked way, I moved the Northwest gun up over the limb in front of me and pointed the muzzle in the direction where both deer first walked down to the flat.

From the doe’s demeanor, I felt confident a rutting buck might not be far behind.

Avoiding the Path of Erroneous Assumption

The optimistic, inner voice that made that erroneous assumption was wrong. The old doe and scruffy button buck were the only white-tailed deer that passed my lair on that crisp November morning. From her actions, I had hoped a fine specimen of a buck would magically appear and stand broadside. No such luck!

Of late, I have received a few emails asking how a new traditional woodsman determines what accoutrements and clothing are correct for his or her persona. The answer is not always easy; the process varies with each living historian and with each persona. And answering, “Do your research” or “stick to common items” means little to someone just starting out in traditional black powder hunting.

The first response newcomers hear is to “seek out primary historical sources and concentrate on one’s chosen time period, geographical location and station in life.” Suffice it to say, the “when,” “where” and “who” of living history each represent huge topics by themselves, but that is not today’s subject. Instead, I want to move past these three concerns and look at a specific narrative and briefly discuss how I evaluate that resource, which is where these email inquiries eventually ended up.

The Falcon: A Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner is one a many “captive narratives” published in the early 19th century. Captive narratives are a literature genre that is unique to America, and many historians classify them as the first true form of American literature. I often turn to Tanner’s dictated life story as a good example for historical study, irrespective of any “agendas” the publisher might have slipped between the lines of Tanner’s recollections.

John Tanner was captured by Shawnee warriors when he was nine years old, about 1789. He was sold to and subsequently adopted by an Ojibwe family and grew up under their tutelage. His adoptive family lived, survived and hunted in the Great Lakes region, ranging from Michigan up through Minnesota. He wintered on the Red River, west of Lake Superior, traded near the Straits of Mackinaw, and dined with Governor Cass in Detroit, about seventy miles east of my beloved North-Forty.

About 1817 Tanner attempted to reconnect with his white family who lived in Kentucky. Unable to deal with life in a white settlement, he returned to his Ojibwe family and lived out his days in the Great Lakes backcountry. He disappeared in the summer of 1846.

Now I’m a slow reader, so it takes some time to wade through a narrative like Tanner’s. Along the way, I highlighted hunting passages that were of interest to me. After all, that’s my main interest, re-creating the simple pursuits of the 18th-century’s last decade. I used a red pen to underline phrases that I deemed important to me and my history-based alter ego. Pencil notations in the margins describe some sections, and yellow sticky notes with one or two word reminders act as index markers for quick reference—if you call thumbing through four dozen sticky notes “quick.”

Now I’m a slow reader, so it takes some time to wade through a narrative like Tanner’s. Along the way, I highlighted hunting passages that were of interest to me. After all, that’s my main interest, re-creating the simple pursuits of the 18th-century’s last decade. I used a red pen to underline phrases that I deemed important to me and my history-based alter ego. Pencil notations in the margins describe some sections, and yellow sticky notes with one or two word reminders act as index markers for quick reference—if you call thumbing through four dozen sticky notes “quick.”

Once the first reading was complete, I set Tanner’s narrative aside and went hunting. Sitting with my back against a favorite oak tree while waiting for a fine buck or strutting gobbler to venture close gives plenty of time to cogitate on an author’s stories. A few months later, I reread Tanner’s narrative a chapter at a time, adding notations as I thought proper.

When I was done with the first chapter, I opened an MSWord document and named it “John Tanner Material Culture.” I saved it in a file marked “Captive Persona John Tanner Narrative,” which was inside the master file, “Persona Development.” I then started recording key words from the phrases, sentences or paragraphs I had marked, followed by the page where that reference can be found:

Before capture:

“We took two candles…” (1)

“…where my father bought three flat boats…” (1)

“…I had partly filled with nuts a straw hat which I wore…” (3)

By focusing on key words rather than copying the whole quote I can do a search of the entire outline that I eventually created. I simply click on “Editing,” then “Find” and type in “candle.” Any passage that mentions that key word will come up highlighted in yellow.

The outline process does not require a lot of additional time, especially when done after reading each chapter. The finished narrative outline sums up the material culture at Tanner’s disposal, or at least what he thought enough about to write down. In addition, I found the exercise of immense help in clarifying my thoughts regarding what this historical character possessed and used on a regular basis.

Doing the same with Jonathan Alder’s narrative or that of James Smith or Mary Jemison, gives a different individual’s perspective to a returned captive’s possessions and what he or she deemed important for daily life. And it opens the possibility of other accoutrements or even processes used by an historical character who fits within a persona’s “when, where and who” limitations.

For example, Tanner mentions “carrying straps” in passing (Tanner, 170), but Smith describes “carrying strings” and how they were used in a hunting context to drag deer back to camp (Smith, 81). If another captive narrative mentions this artifact, then a living historian has not only added documentation, but also a broader insight into how a carrying string fit within a returned captive’s daily lifestyle.

Sometimes dialog recorded as a backcountry exchange holds a guiding principle, too, like the sentence I so often quote from Jonathan Alder when he admonished young Tom Springer for not thinking ahead:

“You never see an Indian start out without his gun, tomahawk, butcher knife and blanket.” (Alder, 126)

Thus, one of the easiest ways to determine what accoutrements and clothing are correct for a given persona is to take a narrative and outline all of the passages that mention the material culture that individual had at his or her disposal.

If an item was significant enough to spend a few words on, then I feel my alter ego had best consider the inclusion of that item in his kit. Likewise, if an item is conspicuously absent from all the narratives, unless it was so common that it did not need mention, then the historical me must give careful consideration to doing without it.

As I try to emphasize to newcomers, when I outline an ancient woodsman’s life story, I always surprise myself with first, what I missed when I read a hunter hero’s recollections, and second, how over the course of a narrative, the author does a pretty decent job of telling the reader what resources he had available.

Outline your favorite hunter hero’s life story, be safe and may God bless you.