-

Recent Posts

Categories

Archives

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

Blogroll

Forums

General Living History

Historical Sites

Organizations

Artists

“Bear Hunt Retold”

Posted in Bear Hunt, Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “Bear Hunt Retold”

“Maybe It’s Your Eyes…”

“Hhuuttt,” the soft, subtle cluck sounded closer. A pitiful sigh oozed from frustrated lungs. A warm, pleasant October sun hugged a distraught woodsman as he sat back against a solitary cedar trunk. The sweet scent of drying corn perfumed the grassy clearing, but did little to dissuade the somber mood. A moist tongue damped parched lips. Tired eyes squinted through brass-rimmed spectacles that eased up and down, seeking the best focus.

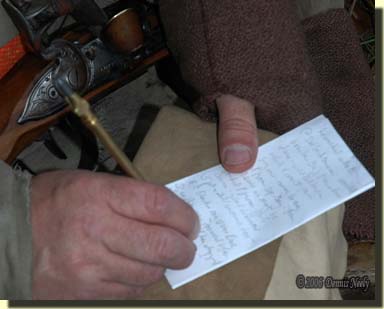

Still gripped by the left hand, the white page rested upon the weary hunter’s thighs. The woodsman’s right index finger stopped at each notation on the bottom of the page. Fifty-four paces distant, less about six, a wild turkey hen emerged from the cedar grove and walked tall into the afternoon brilliance. A few herky-jerky steps and the bird paused. It looked north, then south.

A half-dozen cautious steps westward brought the fowl to the first wagon rut. It turned its head a bit, then pecked the ground twice. Gaze north…gaze south…five steps to the second rut ended with another pause and the same concerned surveying of the sun-drenched clearing. The bronze beauty stood for several minutes. A red-tailed hawk circled silent over the far ridge. Sandhill cranes chortled off in the distance, near the River Raisin’s lily-pad flats.

A half-dozen cautious steps westward brought the fowl to the first wagon rut. It turned its head a bit, then pecked the ground twice. Gaze north…gaze south…five steps to the second rut ended with another pause and the same concerned surveying of the sun-drenched clearing. The bronze beauty stood for several minutes. A red-tailed hawk circled silent over the far ridge. Sandhill cranes chortled off in the distance, near the River Raisin’s lily-pad flats.

Four turkey paces beyond the wagon trail the hen whirled around, cocked its head and peered into the cedar grove. The bird’s body grew rigid, exuding woodland alarm. Deliberate steps became longer, quicker strides. I counted twenty in all, but did not chuckle as I so often do.

My gaze returned to the paper. The black numbers on the yellow steel tape did not lie. “Fourteen and a half inches,” I whispered as I scrambled to my feet, returned to the Northwest gun that rested against the pickup’s open tailgate and began shuffling through the targets in the orange file folder. “Maybe it’s your eyes,” I said to no one as I again pursed my dry lips…

Solving a Perplexing Problem

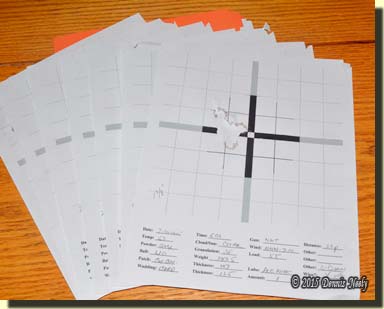

Loading “Old Turkey Feathers,” my smooth-bored trade gun, using historical wadding methods has introduced a host of ballistic questions into the last year or so of range practice. The central question is: “How close to modern competition accuracy can I get using leaves, grass and natural wadding materials with a round ball projectile?”

Previous shot load tests, using both lead and bismuth of varying sizes, with natural-material wadding match the results of using cards and fiber wads. To back up these findings, in June, 2015, I had the opportunity to have my natural-wadding patterns evaluated through computer analysis. Both my clay bird and turkey loads scored in the upper percentile compared to modern shot loads fired through a cylinder bore, but six scrumptious wild turkeys plus a few squirrels and rabbits already knew that to be true.

To achieve a satisfactory answer, I felt I needed a baseline target using a competition load that produced the best performance from “Old Turkey Feathers.” The goal was to establish “an average group” that represents “repeatable consistency,” not a fluke, one-hole group that can only be achieved once every how many targets when five lucky shots just happen.

To minimize human error I shot using a bench rest. I began at 25 yards with the intent of working my way out to a maximum effective distance, which I thought would be about 65 yards, give or take. In recent years, especially when loaded with natural wadding, I like to limit the selection of my lairs to offer a maximum shot of 50 paces and under.

But the results of the first practice session were disappointing; the groups averaged about six inches, center-to-center, at 25 yards. These groups were not consistent with past competition experiences. I spent an hour or so reviewing the notes in Old Turkey Feathers’ file. One-by-one I eliminated past issues. I sought advice from other shooters, including a couple of bench rest competitors who have never steered me wrong. The groups tightened a bit, but never approached what I knew the smoothbore was capable of.

Then on that afternoon in October, I decided to see what I could do at 50 yards. Ten shots later I was stunned to the point of sitting against that cedar tree. When the hen turkey turned around and headed back in front of the 50-yard target frame, I decided I better change my course, too. I believed I had exhausted all possibilities associated with the gun and the load. All that remained was me.

I reasoned that if the problem was my eyes, then I should see similar disturbing results firing a different gun. I have a .40-caliber Dickert rifle that I built in the late 1980s. An hour later I was back at the range dumping off a fouling shot. I was shaking; I was scared my eyes might be the culprit.

Once calmed down, the first shot on a fresh target on the 50-yard board hit an inch and a half low and an inch to the left of dead center. I thought to myself that that was respectable, considering I hadn’t shot the Dickert in about eight years. All ten shots hit low, but including two flyers to the right, the center-to-center group was two inches by two and a half inches. My eyes were not the problem, much to my relief.

Perplexed, I again sat against the cedar tree as I thumbed through the targets. That hen, I assumed it was the same one, clucked again. I expected her to walk out, farther down range. As I watched and waited, my mind mulled over the variables. With a start, I realized I just shot out of the fixings in the .40-caliber box, using a different can of 3Fg black powder.

Perplexed, I again sat against the cedar tree as I thumbed through the targets. That hen, I assumed it was the same one, clucked again. I expected her to walk out, farther down range. As I watched and waited, my mind mulled over the variables. With a start, I realized I just shot out of the fixings in the .40-caliber box, using a different can of 3Fg black powder.

After posting a new target on the 50-yard frame, I duplicated Old Turkey Feathers’ last load, only I used powder from the .40-caliber can. When I purchase powder, I write the date on the top with a felt pen. To be sure the contents were different I checked the batch numbers on the can bottoms. The first death sphere hit an inch low and an inch to the left. Four shots later I saw a group that was consistent with what I know the Northwest gun is capable of—just shy of four inches.

The next ten shots at 25 yards grouped low and to the left in a ragged hole that measured two inches, center-to-center. I penciled “2 ¾ inches” on the target, taking into account the one flyer that wandered above the centerline.

That problem nagged me for several months. The loss of accuracy was particularly troubling, because it was not consistent with thirty years of competitive shooting history. Further, I was very careful to fiddle with only one loading component at a time as I tried to discover what caused the change.

In hindsight, I should have switched powder lots sooner, but my source has been so reliable over the years that I assumed the powder was not the issue. With that oversight I violated my own mantra: “Assume nothing, verify everything.”

To make matters worse, in Old Turkey Feathers’ file there is a note regarding the time I tried a new powder manufacturer at the urging of several other smoothbore shooters at Friendship. That was a dozen years ago. My trade gun did not shoot well with the new brand.

According to the note the groups opened up a couple of inches and the bore fouled more than normal with their 3Fg granulation, at least with a round ball. The powder performed just fine with a shot load, so I burned it up on the quail walk and sporting clays ranges.

About a quarter of the can remains, and it is marked accordingly. Again, out of curiosity, I plan to see how it performs in the Dickert rifle and at the pattern board. By mid-October I had the baseline load that I needed, and I worked on adjusting several natural material wadding combinations. I discovered I can shoot better with my re-enacting glasses than I can with my daily pair and most important, that the grouping problem is not my eyes.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Research, Safety, Wilderness Classroom

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

3 Comments

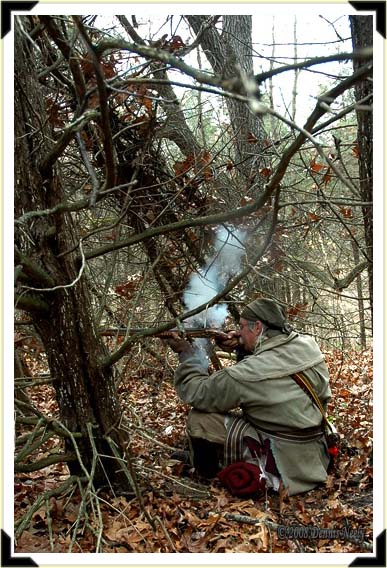

“Successful Ambush”

“Snapshot Saturday”

A quick move and a hasty fort-up behind a random cedar tree tipped the scales in the woodsman’s favor. The wild turkey circled slow, but her soft, inquisitive clucks betrayed her caution. Then ‘Old Turkey Feathers’ spoke with deadly authority on a mild November morning in the Old Northwest Territory, east of the River Raisin, in the Year of our Lord, 1798.

Posted in Snapshot Saturday, Turkey Hunts

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

1 Comment

A Special Thank You

About this time each year I receive a “Year End Stats” report from WordPress. The information is basic, nothing flashy or worthy of fanfare. “Unique views,” a common measurement of a site’s activity, are up over 30 percent for the past year. I have you, my loyal readers, to thank for that—Thank you, and may God bless all of you for searching out my scribblings.

For a living historian who just wants to slip away to the North-Forty and partake of 18th-century pleasures, the concept of entertaining regular visitors from 105 countries is mind boggling, humbling and a bit scary. The majority of you, “dear readers” as John James Audubon used to write, arrive from the United States, Canada, Australia and the Czech Republic.

As fellow time travelers, or maybe just inquisitive onlookers, you knock at the door all hours of the day or night, which one might expect. My deepest hope is that the hospitality you receive satisfies your reason for seeking this site out.

Finding time to write in 2015 was difficult. I surprised myself when I discovered I had the same number of posts as in 2014. As I look ahead to 2016, I would really appreciate some feedback from you on what you like, what you don’t like and what you would like to see on these pages. Email is best, but comment below if you wish.

Finding time to write in 2015 was difficult. I surprised myself when I discovered I had the same number of posts as in 2014. As I look ahead to 2016, I would really appreciate some feedback from you on what you like, what you don’t like and what you would like to see on these pages. Email is best, but comment below if you wish.

Again, thank you for visiting and supporting traditional black powder hunting, be safe and may God bless you all.

Posted in General

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on A Special Thank You

“The Telescope”

“Snapshot Saturday”

Posted in Hunting Camps, Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “The Telescope”

Sometimes ‘Yes,’ Sometimes ‘No’

Killing lost its luster. Canada geese ke-honked above the tree tops. Cranes chortled to the west at the River Raisin’s sandy flats. Two blue jays screamed to the east, at the corner of the nasty thicket, near the barberries. In time, five black-capped songsters populated two witch hazels. “Chic, a-dee, dee, dee, dee… chic, a-dee, dee, dee, dees…” Their rousing chorus filled the 18th-century forest that fine October morn.

Then a young fox squirrel spiraled down a red oak. Its little black claws scratched the rough bark as it advanced earthward. The first bounce into the dry leaves was loudest. Dirt and duff flew as this forest tenant searched for a breakfast morsel. Little did it suspect a Northwest gun, charged with a swarm of dormant death bees, rested across a returned captive’s bare thighs.

Not long after, a second fox squirrel appeared on a hickory’s lower limb, some distance to the south, well beyond the smooth-bored trade gun’s range. This squirrel lingered in that tree with no apparent reason for its deliberate comings and goings from branch to branch. The creature’s bushy tail flicked and flitted with a nervous unending twitch. Several times it slipped behind the shag-bark’s modest trunk as if uncertain where to go next.

A gray squirrel, displaying the opposite tendencies, descended a good-sized red oak on the sunny side. Sitting upright in a sunny spot, its tail curled against its back, the little beast surveyed the forest floor. A gentle southwesterly breeze carried fall’s magnificent  tannic perfume. The gray made no noise as it bounded off in the direction of the elongated scrape beneath the ironwood that grew near the hollow sassafras.

tannic perfume. The gray made no noise as it bounded off in the direction of the elongated scrape beneath the ironwood that grew near the hollow sassafras.

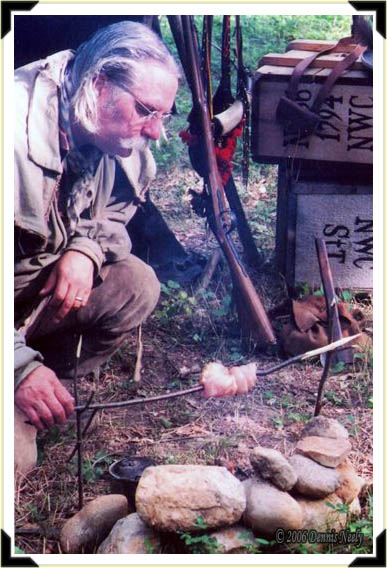

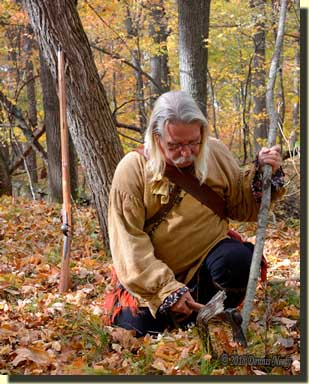

Supple saplings suitable for bending to form a wigwam occupied my mind that morning. One lurked to my right. Nestled among others, towered over by a keg-sized red oak, that sapling would soon meet its end.

After getting to my feet and leaning the Northwest gun against a nearby sassafras, the ax slipped from the sash that bound my weathered, yellow-dyed linen shirt. Two swift strikes toppled the cherry, leaving a chisel-like point. With the sapling’s base held firm in my left hand, the blade skittered to the right, cleaving thin branches flush with the trunk. In all, twelve culls of varying sizes suffered the same fate.

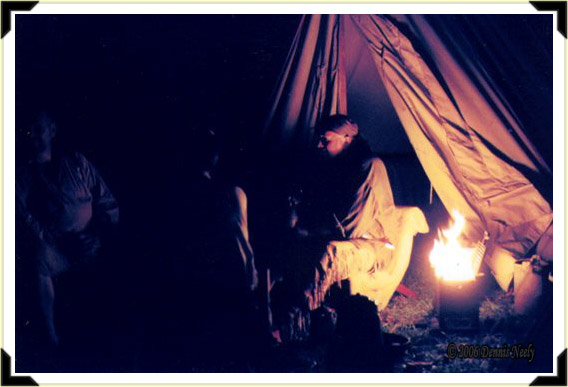

Tiny Steps to Future Success

About every other year I set the goal of building a period-correct shelter to act as the center for that fall’s traditional hunting adventures. Current research usually inspires the camp’s design, and the dominant persona I intend to use has a great influence on the shelter’s style. Some years I achieve that goal and some I don’t. In the latter instance, a prior year’s camp is usually available, either for use “as is,” or to modify to fit the circumstance.

But on a clear day in the spring of 2014, a stout limb fell and flattened the Meshach Browning “cedar brush camp,” removing that possibility in a rather scary manner. In addition, only the rafters of the “mallard duck lean-to” in the cedar grove remained, plus the camp did not suit my emphasis on Msko-waagosh’s returned native captive persona.

As so often happens, too many life commitments consumed the summer. Faced with no usable option by late September, I rolled out my blanket wherever I pleased, just as I expected John Tanner did, or would. As 2014 drew to a close, I swore 2015 would be different.

Constructing an Ojibwe wigwam for the 2015 fall hunting seasons held a prominent place near the top of this living historian’s “to-do list,” along with spending as many days afield chasing wild turkeys or white-tailed deer as possible. When Darrel Lang and I planned that day’s sojourn, I told him I intended to start on the wigwam, rain or shine.

Later that morning a British ranger hunting out of Fort Detroit joined me as I leaned the saplings against an oak. When I vacillated on the shelter’s location, Darrel suggested an alternate spot, flat and sequestered. We went to work marking out the location of the twelve poles, driving a stake to make the hole in the soft earth to receive each sapling and selecting the right-length pole for each bent.

Later that morning a British ranger hunting out of Fort Detroit joined me as I leaned the saplings against an oak. When I vacillated on the shelter’s location, Darrel suggested an alternate spot, flat and sequestered. We went to work marking out the location of the twelve poles, driving a stake to make the hole in the soft earth to receive each sapling and selecting the right-length pole for each bent.

When we started bending and lashing saplings, the crooked culls fought our efforts. Nice straight saplings would have worked better. The arches were not as uniform as I would like, and a couple broke, which slowed the wilderness classroom lesson. I know Tanner’s family would have axed prime stock, but I can’t bring myself to cut a good young tree that someday might make a fine saw log.

As mid-afternoon approached we left the half-framed wigwam and returned to chasing wild turkeys in earnest. The wigwam project sat idle for almost three weeks—more demanding circumstances took precedence, just as they had the year before.

The next opportunity to work on the wigwam came the weekend before Michigan’s firearms deer opener. I asked two of my grandsons if they would like to help. Msko-waagosh overlooked their camo coveralls. Late-eighteenth-century, youth-sized trade shirts, leggins, breechclouts, moccasins and silk head scarves found their way onto papa’s ever-growing “to-do list.” Nightfall ended that outstanding wilderness classroom session, much to everyone’s disappointment.

The next opportunity to work on the wigwam came the weekend before Michigan’s firearms deer opener. I asked two of my grandsons if they would like to help. Msko-waagosh overlooked their camo coveralls. Late-eighteenth-century, youth-sized trade shirts, leggins, breechclouts, moccasins and silk head scarves found their way onto papa’s ever-growing “to-do list.” Nightfall ended that outstanding wilderness classroom session, much to everyone’s disappointment.

Late in an afternoon during the first week of deer season, I finished lashing the horizontal saplings to the bent poles. I started fitting canvas to the frame. The rectangular canvas did not fit the arched contour well. The second piece went up better. Then I realized that if the wigwam’s diameter was about a foot smaller the canvas pieces would fit much better, but it was too late to start over. The intent was a one person shelter, and what I ended up with is adequate sleeping space for three adults. Again I ran out of daylight.

Unlike last year’s dreadful cold, this fall’s weather was mild and pleasant. I couldn’t get enough hours in my 18th-century Eden. Additional demands for my time, driven by the unseasonable weather and circumstances totally beyond my control, gobbled up hours allotted for pursuing whitetails. I made the best of the situation. I don’t regret those choices, but it was at the expense of finishing the wigwam.

Despite accepting life as it is, the historical me still feels a sense of disappointment and deep frustration. Yet, I learned a tremendous amount from the wilderness lessons that surrounded the wigwam, and there is an offsetting degree of elation that accompanies that gain.

I share this experience and reflect upon it, not because it represents a failure, but rather because it demonstrates the tiny steps that are sometimes required to inch closer to a future success. For traditional black powder hunters so many of the lessons learned and so much of the knowledge acquired is based on trial-and-error, hands-on participation in a woodland setting orchestrated to simulate, as close as possible, one recorded in a centuries old journal entry. Again, sometimes we, as living historians, achieve our goals, and sometimes we do not.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Hunting Camps, Turkey Hunts

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

3 Comments

“Fresh Fowl”

“Snapshot Saturday”

Posted in Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “Fresh Fowl”

Reclaiming Inborn Traits

Gray clouds spit a fine mist. Winter moccasins whispered on damp leaves. First the maple, then the white oak, then the towering basswood offered cover. Two more maples and a jagged red oak trunk brought the course to the edge of the mucky bottoms. Mossy, serpentine roots, sedge grass clumps and rotted, thigh-sized, barkless branches eased the crossing and kept the center-seamed moccasins just damp, not wet and muddy. Maneuvering around a tangled clump of ironwood encircled with autumn olive bushes took time.

Footfalls hugged the nameless island’s northwest edge. The sandy bump, sequestered in the midst of the River Raisin’s bottomlands, rolled tall enough that a woodsman could not see from the west bank to the east bank, yet the isle was no more than thirty paces broad. A bedroll bound with a leather portage collar eased down on the raised, moss-covered root system of a trio of yellow birch trees, twenty paces off the island. Upwind, a trail angled southwest and slightly away from that lair.

The bottoms remained quiet. The mist ceased. A gentle breeze came and went, as did a pileated woodpecker that flitted from treetop to treetop. Such solitude characterizes the waste land that flows from the hardwood forest to the cattails that border the Raisin’s banks.

The bottoms remained quiet. The mist ceased. A gentle breeze came and went, as did a pileated woodpecker that flitted from treetop to treetop. Such solitude characterizes the waste land that flows from the hardwood forest to the cattails that border the Raisin’s banks.

In time, blue patches of clear sky broke through the foggy gray soup that hung low over the river. A rousing chorus of “Chic, a-dee, dee, dee, dees” interspersed with the chirping of two song sparrows brought hope to a slow morning.

Then the soft snap of a tiny twig tightened the grip on the Northwest gun’s slender wrist. The almost imperceptible thump of a cloven hoof upon the island’s crest sent my thumb into a fidgeting dither on the lock’s jaw screw. “Patience…patience,” I mouthed in silence as I shifted my thoughts to juice trickling from a succulent apple.

A young doe’s head came into view first. She plodded on the trail, stopping now and then to sniff the air and look upwind. She gave little mind to the downwind side of the island. A bigger doe, her mother no doubt, followed about ten paces behind. From their manner, I surmised a buck would not trail the pair. Tense muscles relaxed and I contented myself with watching and studying those passersby.

Mental Telepathy and White-tailed Deer

I scribbled two notes in my journal after those two does passed, the first read “Thinking of juicy apples,” and the second, “What do the deer see?” Now the first notation will only confirm my daftness, but I suppose this fits with my constant babbling on about time travel. Well, no matter…

When I first started pursuing white-tailed deer in earnest, I met Gene Wensel at an outdoor show here in Michigan. He was one of the top gurus of big buck hunting at the time, and I don’t believe that mantel has ever left his shoulders. I think part of my attraction to Mr. Wensel was his reverence for Fred Bear, another of my hunter heroes. I bought his book, Hunting Rutting Whitetails, and that autographed copy still sits in a hallowed location on my bookshelf. It’s about due for another read.

Now in the last few years, based on readers’ questions, I have come to realize that a given part of the hunting methodology that I employ as a traditional woodsman has become relegated to the subconscious netherworld. I chuckled that morning, when I realized I half-consciously shifted my thoughts to the creamy flesh of a ripe apple and the sweet juice that trickles forth in preparation for a mighty buck’s hoped for appearance. That ingrained habit is a direct result of Gene Wensel’s early influence.

“The point I’m trying to make,” Wensel writes, “is that civilized man has lost a lot of previously inborn traits, instincts and abilities over the centuries. For literally generations he has been bred to make life easier for himself. He’s relied less on the necessary means of survival, at the same time dulling his old inbred talents as a true hunter…” (Wensel, 86)

The discussion that follows in his text deals with whitetails possessing a “sixth sense” for detecting danger. But as he works toward a chapter dedicated to the hunter embracing a “positive mental attitude,” he states:

“…the biggest question is not whether this sixth sense exists, but whether we can do anything about controlling it. And even more important, whether or not we may be able to reverse these brain waves to attract rather than repel game…” (Ibid, 87)

At that time, I started thinking through all the “almosts” that dominated my hunting. I realized that in every case my mind was centered on the death of the approaching buck—super negative, anti-survival brain waves? Maybe there was something to Wensel’s ideas and maybe there wasn’t, but the notion was worth a try. That’s when I started thinking happy thoughts about succulent apples. Did your mouth water when you read about the juice or did an inner voice yell “DANGER!”?

What Do the Deer See?

In those early years, I learned to stalk deer. I didn’t know that a hunter wasn’t supposed to “put the sneak” on a whitetail. That notion ran counter to stand hunting, a sacrilege beyond redemption, I learned.

As my experience grew and stalks became more complicated, situations arose where I was in the wrong place at the right time. To remedy the location problem, I started circling from a poor location to a better one by loping along on earthen deer trails. After all, those byways were the most advantageous means of getting from one place to another. I wish I could still move with that youthful combination of stealth and agility…

On more than one occasion I passed bedded deer that just watched and showed no signs of fear as I hustled along. Trying to improve my advantage on a nice buck, I once jogged past a nicer buck—talk about conflicts. This practice evolved from necessity in the laboratory of the wilderness classroom. Again, no one told me you weren’t supposed to leave scent on active deer trails.

On more than one occasion I passed bedded deer that just watched and showed no signs of fear as I hustled along. Trying to improve my advantage on a nice buck, I once jogged past a nicer buck—talk about conflicts. This practice evolved from necessity in the laboratory of the wilderness classroom. Again, no one told me you weren’t supposed to leave scent on active deer trails.

Using deer trails to navigate from one place to another taught me another valuable lesson: view any stand from the perspective of the deer. Most hunters choose a stand based on the wind and the potential for a high percentage shot, yet they never consider what the deer sees when it passes along that throughway.

I would venture to say that 95 out of 100 hunters, modern and traditional, would have chosen to sit with their back against the two, powder-keg-sized white oak trees that grow from a common root on the northwest side of the nameless island. Those trees offer a comfortable spot, descent cover with a good view of the bottoms and a thirty-plus-pace shot at the trail coming from the cattails at the river—everything a hunter might hope for, taking into account that we restrict hunting to the ground on the North-Forty.

But trails go two ways. A rather rough walk from the river to the island reveals that the forked oak is a prominent tree that draws one’s attention as soon as a forest tenant breaks into the bottoms from the cattails, a hundred paces out. Likewise, approaching from the northeast, the trees’ whitish-gray bark almost glows like a lighthouse beacon; all but the lower foot of the trunks are visible, again eighty or so paces distant.

One of the advantages of still-hunting is that it gives the woodsman an ever-changing perspective of the forest or fen. And with that limited movement through the forest, the woodsman gains a better understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of a given tree top, an old cedar tree or a clump of yellow birch trees. Armed with that knowledge, a would-be 18th-century woodsman can reclaim a small portion of a lost inborn trait by recognizing what to exploit and what to avoid.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Deer Hunts, Skills

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

1 Comment