Monday, 25 April, 1763:

“Ccttt…,”

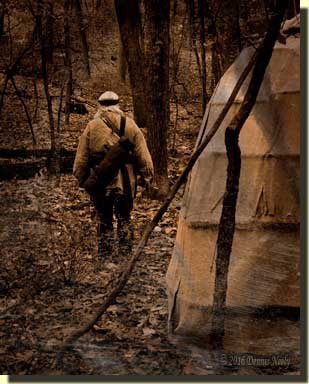

“To the right, by the tipped maple with emerging greenery,” Mi-ki-naak surmised. The second sharp “click” proved the first was not imaginary. The returned white captive fought the urge, did not turn, did not steal a glance. Brown eyes squinted. Muscles prepared, but did not tense. An eager thumb bumped the French fusil’s cock, but did not set. No need to worry, the thriving ground juniper, one of the last surviving on the ridge’s west slope, concealed the returned captive’s deathly shape.

“Ccttt…,” a second wild turkey joined in, this one behind and to the northeast. “Ccttt…” Another popping, clicking sound came from the witch hazel stand, or there about.

“Whit, whit, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu…” A crimson cardinal marked his territory, perched up in a poplar sapling.

“Chic, a-dee, dee, dee, dee…” That black crowned songster flitted low, darted up and bobbed on a frail wild cherry sprig with leaves the size of a fox’s ear. Geese ke-honked on the Riviere aux Raisins, past the downed maple, through the soggy bottoms, beyond last year’s dead cattails.

“Caw, caw, caw, caw…” The morning agitations of a flock of crows hung in the air, over the ridge, perhaps near the cedar grove? All the while the clicks and putts grew closer, overshadowing the melodious morning cacophony of a contented glade.

A red head popped up to the right. Through the squinty haze, the young tom appeared under the arched over red cedar tree where a trap set produced four large raccoons the October prior. That bronze shape stopped and began pacing back and forth. Two splotches of red arose. Minutes ticked away like spring water bubbling over the waist-high rocks where the nameless creek begins its passage through the great swamp.

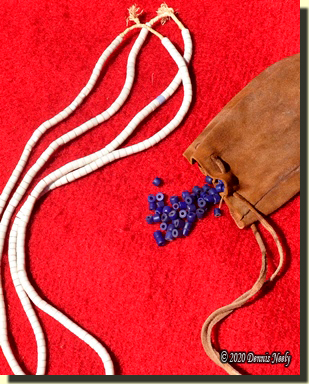

The fidgety gobbler with the tiny black tuft expected a hen to jump up and run to his love musings. She hid in Mi-ki-naak’s shot pouch, or rather the single wing bone did. Hearing no answer, that bird went silent. The others did the same. With caution, the wild turkey embarked on a circular stalk to the south.

“Oh Creator, by your will grant a clean kill or a clean miss,” the returned white captive whispered…

Thoughts on Natural Wadding

The best jake in that group of six young turkeys had a three-inch beard. Mi-ki-naak wanted a bigger bird. Perhaps not period-correct, he passed on the lot, even though that one got within twenty paces of the hemlock lair.

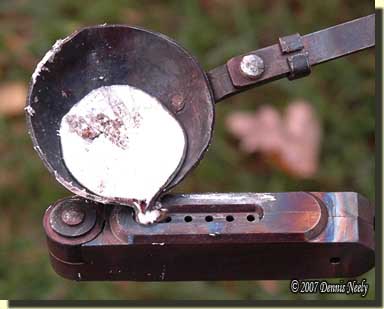

Fall maple leaves, picked up in the woods, damp enough to form into a ball, neither squishy wet nor crumbly dry, secured the powder charge and the anxious death bees. It doesn’t seem possible, but my alter egos have been using natural wadding in their smoothbores for ten years. I had to check my range notes to confirm that time span.

Of late, a number of black powder shooting enthusiasts have jumped on the natural wadding bandwagon, offering opinions and rules of thumb based on a handful of shots. From what I can discern from their statements, no one uses natural wadding with any regularity, either for hunting or target shooting. And few take wild game, or possess journal entries accounting for consistent success, other than my alter egos.

One comment that sticks out in the articles and videos is, “Don’t catch the woods on fire!” That certainly sounds encouraging. I had the same concerns early on in my quest to load as my hunter heroes did, or as close to it as possible. Before the first leaf wad squeaked down “Old Turkey Feathers” bore, I sought out answers from several mentors, one in particular who never gave me a questionable answer to any of my queries.

His statement was simple. “All of the oxygen in the breech is consumed by the combustion of the powder.” Being a former fire chief, he continued with, “You need oxygen to complete the fire triangle [fuel, sufficient heat and oxygen in the presence of a sustainable chain reaction], without oxygen, combustion cannot take place.”

He went on to discuss burning patches on the range, which usually indicated a synthetic fabric blend, not 100 percent organic fibers. The other situation was the use of a patch lube or solvent that contained a component with a low flash point. Over the years, my experimentation has produced smoldering patches, in part attributed to both potential causes.

About thirty years ago, I discovered a smoke plume after downing a ring-necked pheasant on a dry October evening of zigzagging in the swamp. It was not a glowing ember, just a light smoke. Regardless, it scared the daylights out of me.

But true to the advice, this was the first, and last, time I soaked the fiber wads in a commercial petroleum product, recommended in an article in a major black powder magazine. Based on that incident, the “Don’t catch the woods on fire!” caveat should apply to fiber wads, too. It seems modern-day litigation terrifies us all. After that hunt, I went back to a water-soluble compound for fiber wads with no issues.

There is no question that green grass or leaves will not burn. As an aside, my studies show the green leaves do a better job of “scrubbing the bore,” than dry wadding. I only use dry leaves for late fall, winter and early spring wadding, due to availability. To date, I have never had a dry leaf wad combust or smolder. When pulled, they are as tight-packed as standard fiber wads, which do not burn, because the ignition temperature is high enough to not be an issue—and it shouldn’t anyway if my mentor was correct.

Yes, stories abound about smoldering patches and sometimes wads. As I said, I have them too. But upon further study, an underlying reason is always present. I have looked hard for documented research to prove or disprove my mentor’s theory. To date I have not found any. I would welcome solid scientific tests, data and/or evidence, if any exists.

The stories don’t cut it, because an important factor is overlooked and left out. In the meantime, caution is prudent. Based on ten years of using natural wadding in the field, my finding is that the probability of catching the woods on fire is minimal. But never say “never…”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.