Lines and creases crisscrossed black ice. God’s artistry drew attention to the fragile, frozen skin covering the water that filled the huckleberry swamp. A light touch of snow dampened brittle oak leaves, hushing the noise of each footfall.

“Tu-Tu-Tu-Tu…” an unseen cardinal twittered. Another answered, “Whit, whit, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu…”

The morning’s course passed a crooked-trunked wild cherry, stepped around a broken red oak, then paused at a circle of stones, almost buried by two fall’s worth of rotting leaves. That hunting camp had not been used in a decade, perhaps longer. The rocks a distant memory renewed by happenstance.

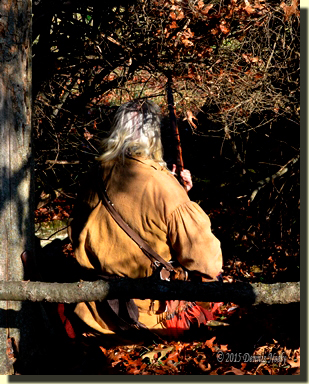

A fox squirrel dug for an acorn, six or so hops to the south of the red oak with the massive burl. Startled by an unexpected observer, the forest tenant bounded thrice, circled a young hickory, then hung upside down as it gazed at the interloper. A few minutes later, the squirrel ran to a maple, then to another oak. With each change of trees, the grinning woodsman advance the same distance as the squirrel.

This wilderness game continued over the narrow isthmus that divided the nasty thicket from the huckleberry swamp. At the east end, the bushy-tailed squirrel crossed the conjuncture of doe trails that funnels from the west face of the big ridge onto the isthmus. The returned captive again paced off the same distance, about a rod and a half.

Sharing the same caution as the squirrel, the woodsman looked about, seeking any sign of danger, any reason for concern. Casual snowflakes drifted. The air smelled clean and fresh like that of early November. But it was mid-April, in the Year of our Lord, 1795.

This time-traveler from two-plus-centuries hence glanced down. The tip of an antler tine, the size of his little finger, protruded from the oak leaves. He bent down, retrieved the prize and tried to remember which first-year buck sported this small, three-point right-side antler. Msko-waagosh could not remember.

The squirrel paused; its left hind leg a blur of motion as it scratched is midsection. It bounded to a large red oak. The woodsman veered north, remaining four trees distant. The tiny white flakes, drifting as if resisting gravity, punctuated the solemnity of the moment. This was the parting place for the fox squirrel and the wayfarer. The squirrel hopped uphill. The hunter continued on the lower trail that skirted the east side of the huckleberry swamp.

Two dozen paces later, a loud chattering commanded attention. The squirrel spiraled around a tall, slender powder-keg-sized red oak. The tree’s first branching was a good forty feet up. In the crown, an accumulation of twigs marked the start of a nest. A Coopers hawk perched on an easterly branch and spread its wings in protest. The squirrel barked in defiance. The hawk dove. The squirrel ducked behind the trunk. The hawk fluttered in midair. The squirrel chattered. The hawk looped up and came to rest on an upper limb.

Undaunted, the fox squirrel twitched its tail and worked up the tree. The hawk uttered a soft squeak, then dove again. In the flapping of wings and darting and dodging, it appeared the hawk dislodged the critter’s left hind leg. The hawk swooped around the trunk, then settled into a different oak’s thin, outer twigs. The squirrel chattered, then started down the tree. The woodland confrontation was over. The hawk screeched in victory, but flew uphill and vanished over the ridge crest.

And with that, the returned captive stopped leaning against a modest poplar. Shaking his head at the morning’s drama, he turned and continued down the trail.

A Great Time to Outline

The book, Scoouwa: James Smith’s Indian Captivity Narrative, is again sitting on my desk. I started outlining Smith’s recollections in the winter of 2017. While researching trade knives, I realized I had not completed that task.

Between trying to write, the demands of home healthcare and trying to maintain a farm, I have little time for “additional projects.” I scratch my head at the clueless attitude of the Hollywood elite when it comes to all their “new-found time” and “boredom.” It would be amusing if it weren’t so tragic. I have piles of work they could do, but I’m not sure of their competency. Enough of that…

One of my goals for the spring is to regain a grip on my living history addiction, or rather to encourage this passion to run rampant again.

I snuck a side project into this year’s winter clean up on the farm. I’ve spent an hour here and an hour there skidding out some of the cedar trees killed by the utility company’s forestry crew in 2016. Perhaps “killed” is a harsh word. I must confess that I have the soundtrack for “The Last of the Mohicans,” playing as I write this. I feel a certain degree of defiant emotion charging through my veins. I suppose that is weaving through my word choice. So be it. At any rate, there was no reason to cut and remove so many trees that posed no danger to the transmission lines.

Unfortunately, this project got away from me for the same reasons everything else was put on hold. I had a rustic-log furniture company that was interested in purchasing the cedar logs, but that fell through. So now my alter egos get first dibs. Or is that second dibs? No matter.

About half of the trees are of a proper size for construction of a 1790-era lean-to. I have three sort piles with more logs coming. Thinking through the construction details for the trading post hunter’s lean-to shelter brought me back to James Smith. Confused with my thought process, yet?

It is clear there will be a surplus of “cabin logs.” On a trip to the yarding area, the iron mule’s droning engine lulled my mind back to James Smith’s narrative. I recalled, or thought I did, him telling about making a winter cabin with two rows of stacked logs, a propped up ridge pole and rafters.

That evening, when sitting at my desk, I called up the MSWord outline for Scoouwa… In a matter of seconds, a quick “Find” search sent me to page 45 of Smith’s narrative. I grabbed the book from the shelf and began reading. Now I don’t fully understand Smith’s description; either I’m misinterpreting his words or there is a bit missing. Such is the case with 18th-century missives.

But I’m mulling his winter cabin layout/description as a second shelter for Mi-ki-naak, Smith’s contemporary. I chuckle, because that imagined abode would be a fourth shelter—if I live long enough to complete it. Msko-waagosh needs a new domed wigwam and Mi-ki-naak’s peaked wigwam is shy a few horizontal ribs and a good covering. “You’ll get there, Grasshopper,” I keep telling myself, “You’ll get there…”

A Suggestion for Outlining

I’m big on simple. My outlining process started with John Tanner’s journal, The Falcon… I experimented with the business tools I was familiar with: Microsoft Excel, Access and Word. I settled on MSWord, because the software would do what I wanted, I was familiar with the keystrokes and it was easy to search.

I opened an existing file, “Persona Development,” where I keep tidbits I find while researching. I created a new document and named it “Captive Persona John Tanner Narrative.” I did the same for James Smith’s journal and also for that of Jonathan Alder.

Each outline starts out different, because each editor presents the narrative in a different manner. In Smith’s case, a few lines summarize important points contained in the “Foreward,” “Biography,” and “Introduction.”

An entry in the outline represents a passage that I, as a reader and living historian, deem important. A given phrase or sentence might be unimportant for your portrayal. That is your choice as a researcher.

I do not include the entire passage, only a few brief words that summarize the gist of the author’s observations, followed by the page number where that passage is found. The entries are in sequence as they appear in the journal. I do not group them by subject or any other method. The search function will find all of the words that are pertinent at that moment.

To the right of my tool bar is a section titled “Editing.” Clicking on that choice gives a drop-down menu. I click on “Find,” which opens a sub-window on the left titled “Navigation.” I enter a key word that I think will find the passages that I need, then I hit “Enter.” The word will appear in the narrative window and highlighted in yellow in the text of the document, which in this case is the outline itself. Sometimes it is prudent to search multiple words to find all of the quotes that apply.

For me, as a traditional black powder hunter, the tales of the chase are a priority, even if they are mundane and uneventful. I never know when or where my writing will take a turn, and you would be surprised at how many times a passage that holds little mystique becomes a significant example of the 18th-century, backcountry lifestyle. Second in importance is the material culture: the clothing, accoutrements and yes, insignificant trappings that accompany woodland survival. Personal interactions or other happenings that attract interest are also included.

As an example, the first passage noted in Smith’s journal is:

“Gave the scalp halloo … 21”

Now that doesn’t seem too significant, but added to other captive narratives, the “scalp halloo,” offered upon entering a Native American camp with captives, appears quite often—a “common occurrence” which adds flesh to a first-person portrayal.

“…we found they had plenty of Turkeys and other meat, there; and though I never before eat venison without bread or salt… 21”

This longer excerpt contains words that might be included in a future search, such as “turkey,” “meat,” “venison,” “bread” and “salt.”

“…viewed the Indians in a huddle before the gate, where were the barrels of powder, bullets, flints &c. and every one taking what suited; 24”

Again, a longer observation with many potential search words, unlike “…he borrowed my Bible…64.”

So there you have it, a simple, searchable outline of the daily life of a hunter hero. If you find yourself with time, or if you’re looking for a living history project that will produce future benefits, consider outlining a favorite woodsman’s narrative. You will learn more than you think and have a lot of fun in the process.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.