November’s last day broke with a violent rainstorm. A steady drizzle and a high wind rendered a morning hunt impossible, but by late afternoon the tempest subsided. The air was late-March warm; the mixed stench of night crawlers, stale urine and rotting deer pellets filled the cedar grove. Water dripped. Winter moccasins squished. The year was 1792.

The cedar grove seemed barren of white-tailed deer, yet the evening’s still-hunt progressed at a slower pace than normal. On the one hand, I fought the rain’s aftermath, and on the other, I knew the deer would soon pass through the cedars on their way to the night’s frolic. The wind slowly shifted to the north and caressed my face. At the broad mouth of the big gulley I chose the lower trail.

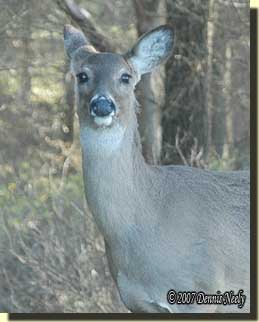

In time, the still-hunt made the great cottonwood. During that pause, three deer, a doe and two fawns, appeared at the edge of the big swamp. One of the fawns took two steps into the clearing, paused and looked about. The second fawn ran past the first. I think the old doe gave a soft, admonishing bleat. The brash youngster stopped stiff-legged, laid her ears back, then surveyed the clearing.

In time, the still-hunt made the great cottonwood. During that pause, three deer, a doe and two fawns, appeared at the edge of the big swamp. One of the fawns took two steps into the clearing, paused and looked about. The second fawn ran past the first. I think the old doe gave a soft, admonishing bleat. The brash youngster stopped stiff-legged, laid her ears back, then surveyed the clearing.

When the three all nuzzled the ground, I sat where I stood. The soaked ground damped the seat of my knee breeches, but in the unseasonable warmth I tolerated the inconvenience.

Despite the eagerness of the fawns, the old doe showed reluctance to cross the small, grassy clearing. She turned southwest, flicking her tail, rolling her ears and bobbing her head up with frustrating regularity. She was never more than two bounds from the fen’s thick, tangled grasses.

Another trio walked around the far knob and milled about, venturing farther into the open, and in a short while, two more met the first three. The cautious old doe settled down a bit, but still displayed a higher level of concern than the others. The eight browsed with a synchronized vigilance; at least one deer’s head was up and watching all the time. An opportunity for me to slip away was never offered.

Judging from the demeanor of the eight, a buck was not expected soon. I understood that that might change in an instant, but that understanding was more folly than reality. Trapped with nowhere to escape, I was left to wallow in my own thoughts. I felt the skin on my rump wrinkle, and the sopping breeches became an almost unbearable irritation.

The does never crossed the clearing on that November evening in 1792. Much to my relief, the dense, gray clouds ushered in an early nightfall. Just at dark the eight went their separate ways, fading into night’s abyss as good deer do, never coming within the Northwest gun’s range.

I scrambled to my feet and sloshed homeward, knowing I must run the cedar grove’s gauntlet and take a stout switching from unseen dead branches, all the while feeling small.

Pursuing a True and Meaningful Re-creation

Traditional black powder hunting can be brutal, sometimes in a physical sense, sometimes in a mental sense. On that particular evening, the last day of Michigan’s regular firearms deer season, the wet knee breeches did not qualify as “brutal,” either in a physical or mental sense; they were a minor irritation that has been overlooked many times before.

Finding myself trapped, alone with my thoughts, was not brutal, either. For me, it is quite commonplace to spend the last evening of a hunting season in a state of melancholy as I reflect on events of the days or weeks prior. Thus, when I started reading George Nelson’s journal, I experienced an unexpected pristine moment, a feeling of kinship with the young XY Company clerk:

“Why then do I write? First, it is to while away some moments & dissipate some thoughts of melancholy that frequently oppress me…” (Nelson, 31)

For lack of a better word, the “brutality” of that evening was a tremendous feeling of smallness that swelled up within me as darkness fell. Perhaps it was triggered by the immensity of the towering cottonwood, or the realization that I was powerless to will the deer closer, or the discouragement of not knowing what action Josiah Hunt or Meshach Browning or Jonathan Alder might take in such a predicament. I don’t know, and expect I never will. That feeling of smallness just happens.

In those moments when I feel small, my mind seems to run with a scary abandon; they have come with some regularity of late. I started researching a new persona a few months ago, and that is a contributing factor. On the one hand, I find the opportunity exhilarating, and on the other, terrifying. Stepping out from the safety of years of familiarity injects a sense of excitement into the endeavor, and at the same time, today’s dependence on solid, primary documentation and a stronger emphasis on authenticity elicit an overwhelming fear of “getting it wrong.”

I felt such a fear at the Battle of Frenchtown. As Lacroix’s infantrymen marched down a street in Old Frenchtown, my mind slipped back in time, which was the hoped-for-intent of the commemoration’s organizers. From my alter ego’s perspective, I saw folks from the future, not just Capt. Lacroix’s militia or the Kentucky volunteers, but the American Army of the Northwest Territory, the British regulars of Colonel Proctor and the women and children of Frenchtown. I realized I lacked the knowledge and expertise to determine if these 19th-century time travelers presented a true and meaningful re-creation. I felt small, left to trust their judgment on the matter.

An hour or so later, when I watched a mid-battle volley of musket fire, I found myself focused on one re-enactor. His linen hunting shirt, black felt hat and overall kit matched that of the others in his unit. He fumbled loading his musket and fired out of sequence with the officer’s commands. Just before pulling the trigger, he raised his head from the walnut stock, turned away from the firelock, closed his eyes and pursed his lips. And that might have happened in the real battle, too.

An hour or so later, when I watched a mid-battle volley of musket fire, I found myself focused on one re-enactor. His linen hunting shirt, black felt hat and overall kit matched that of the others in his unit. He fumbled loading his musket and fired out of sequence with the officer’s commands. Just before pulling the trigger, he raised his head from the walnut stock, turned away from the firelock, closed his eyes and pursed his lips. And that might have happened in the real battle, too.

It appeared this re-enactor was newly arrived on the path to yesteryear, yet he was doing his best to present a true and meaningful impression. I suspect he succeeded with the vast majority of onlookers, but his obvious enthusiasm, his commitment to the historical moment made me feel small again, twice in one day.

For me, there is always an equal and opposite reaction to these feelings of smallness. In the case of the wincing militiaman, I saw myself many years ago, when I first started out. I realized how far I have progressed on the path to yesteryear, and how far I want to go. His enthusiasm recharged my enthusiasm, his commitment firmed my commitment.

I believe this feeling of smallness is a manifestation of our human frailty, a fear of failing or falling short in our humble endeavors. This is natural, but we must strive to keep it in context or it will stifle or perhaps destroy our travels back in time.

But feeling small is also representative of the living historian’s constant process of critical self-evaluation, and there is where the brutality lies. We are, after all, our own worst critics, but that criticism must be constructive and lead to a betterment of our individual impressions and hunting simulations. The key is to delve into our shortcomings and emerge with a new sense of excitement, enthusiasm and commitment to pursuing a true and meaningful interpretation of the past.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.