The soft cluck left little doubt. The faint “arrkk,” uttered in the forest’s somber stillness, fixed my attention on the crest of the ridge to the east. A yellow maple leaf whipsawed side to side. Others followed. The morning’s wispy breeze carried the smell of rain.

Like a spider overpowering its prey, the fingers of my right hand gathered the orange scarf from atop my head, crumpled it in a ball, then stashed it away, inside the lap of the linen hunting shirt. I feared the movement betrayed my deathly presence. Another cluck assuaged a humble woodsman’s anxious heart. Thoughts of fresh game shifted from squirrels to a wild turkey.

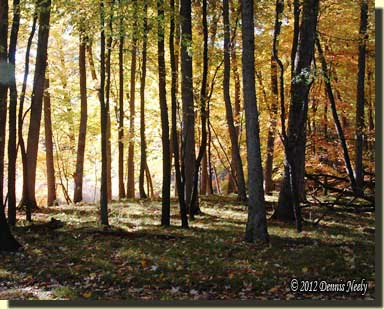

Gray clouds came and went. Light rays raced across the forest floor, whisked away by fast-moving shadows. A fox squirrel teased, high up in a distant red oak on that ridge. As the sunlight changed, I longed to garner a glimpse of a turkey’s bronze feathers or gray head. Minutes dragged by.

Gray clouds came and went. Light rays raced across the forest floor, whisked away by fast-moving shadows. A fox squirrel teased, high up in a distant red oak on that ridge. As the sunlight changed, I longed to garner a glimpse of a turkey’s bronze feathers or gray head. Minutes dragged by.

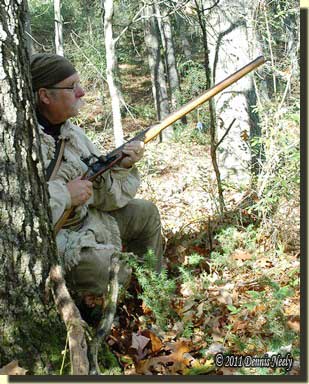

The two clucks charged the cool morning air with a common dilemma: advance or remain hidden. My eyes hacked away at the underbrush, but to no avail. Prudence dictated the later choice, so I remained within the confines of my woodland fort, a tangled oak tree top downed in a blustery rainstorm.

On two prior occasions I witnessed from afar as morning turkeys crossed over the ridge, disappeared in the valley and reappeared, following a doe trail that eventually passed within range of the tree top. I sat tight, content to watch the leaves fall. Another twenty minutes or so ticked away before I spied the first bird, a large hen that spent more time pecking and scratching than looking for danger.

As I rested the Northwest gun on the limb in front of me and snuggled the butt under my right arm, I played through the most likely scenarios for the hoped-for shot. Before sitting, I paced off 28 steps, the effective distance of “Old Turkey Feathers,” and noted a crooked cherry sapling as the first location for the unsuspecting hen’s demise.

When the last of the six birds disappeared, the firelock’s brass butt plate settled against my shoulder. The old hen was the first over the rise, zigzagging beside the doe trail. I could taste the gravy flowing over a slab of white meat and smell the cornbread stuffing. I almost smirked as my mouth watered.

The lead hen stopped in the middle of a long, thigh-sized rotted log, just off the trail. Leaves and dirt flew about. The other five closed ranks, then spread out, rustling leaves with great abandon. The turtle sight lingered close to the big hen. I squinted and prayed in silence. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord.”

“Jay! Jay! Jay! Jay!” A blue jay screamed from a lower branch, maybe 30 paces to the south of the birds. The blue jay was the first I had heard in two mornings, and it startled me a bit, but not enough to cause me to wince or move.

The forest sentinel upset the two smaller turkeys, the ones digging at the far end of the log. Both raised straight up and leered to the south. One uttered a crisp “putt” as the other turned away. It took three deliberate steps, then putted, too. The old hen took notice. In a few heartbeats, all six stared to the south, as two more jays joined the fracas. The bird that first turned away was the first to run. My mouth grew dry as the little flock retreated with long, quick strides and sunlit bronze backs.

Taking Unnecessary Risks

There is no certainty in the 18th-century forest. Traditional black powder hunters are painfully aware of this universal truth. For me, the uncertainty is a big part of what draws me to this joyous pastime. And if we look, this uncertainty fills many of the old hunting tales, either addressed outright or alluded to.

Perhaps no other hunter exemplifies this more than Meshach Browning. That may be because he wrote down the whole story, the good and the bad, the successes and the failures, the triumph of the hunter’s spirit and its frailties, as well. There doesn’t seem to be a chapter where he doesn’t find himself in some sort of predicament, and his usual response is to draw his “large knife” and finish what he started.

Early on in their marriage, Browning’s wife, Mary, spoke of these uncertainties and the dangers that lurked in the forest.

“About the first of October, as I thought it was high time to take my dogs and gun a little, I asked Mary if she would stay at home by herself, or would go to my mother’s and stay, while I went hunting…I promised to return home before dark; and was about to start, when Mary said to me: ‘I feel afraid on your account, for I know you have neither fear nor care of yourself when among the wild beasts; and some day you will be crippled, if not killed. What would you do if you got in the claws of such a bear or panther as you killed last fall, or in the trap this spring? Meshach, they could tear you as easily as a cat would a mouse; and I beg you to take care and not get into their clutches.’

“I assured her that I had plenty of powder and balls; and that, if they attempted to run on me, they must take care of themselves; or, as they raised up to take hold of me, I would be sure to let out a part, at any rate, of what they had inside their black wallets. She said: ‘May God protect you!’ and I started.” (Browning, 90)

Browning came to a swamp and let his oldest dog take wind of the thicket.

“In he went; but he was scarcely out of my sight, when I heard the fight begin…” (Ibid, 91)

In the course of the pursuit, Browning came upon the treed bear. Upon seeing him, the bear dropped to the ground, choosing to take his chances with the dogs.

“I ran the muzzle of my gun against him, and sent a ball whizzing though the middle of his body, but too far back to save a hard fight…” (Ibid)

The bear and the dogs got in a mighty tussle, and then the uncertainty kicked in.

“I had lost my gun in the weeds, and I had no means of defending my dogs, except with a large knife in my belt, which I drew, but not till I vainly tried to find a club. My dogs were getting the worst of the battle; and while he had one of them on the ground, and was biting him badly, I ran up and made a lunge at him, but, like my shot, it struck him too far back, and only entered the liver…” (Ibid)

The bear released the dog and attempted to hide under a log. The dogs kept fighting the bear and the bear the dogs. When an opportunity presented itself:

“…I ran upon him with my knife, and dealt him two or three severe blows, which finished him…” (Ibid)

So many aspects of this encounter of Browning’s beg attention, but the overall point I wish to draw from the passage is the uncertainty that exists in the glade and how we, as traditional woodsmen, tend to get caught up in the moment. In my case, I had that hen shot, dressed and cooked before it ever was within range. The folly of such thoughts is obvious, and we all succumb to them, now and again.

So many aspects of this encounter of Browning’s beg attention, but the overall point I wish to draw from the passage is the uncertainty that exists in the glade and how we, as traditional woodsmen, tend to get caught up in the moment. In my case, I had that hen shot, dressed and cooked before it ever was within range. The folly of such thoughts is obvious, and we all succumb to them, now and again.

But the uncertainty also comes into play with regards to our own personal safety in the woods. While reading Browning’s exploits, I shudder at the unnecessary risks he took. His actions are simply not safe. He would be a fine candidate for having “Don’t try this at home” tattooed on his forehead; at the very least, Mary should have embroidered those words on his hunting shirt. And, I think, from her statements and constant concern, Mary was very much aware of the dangerous situations her husband put himself in, too. Wives know us better than we know ourselves.

Wisdom sometimes accompanies age, or so I’m told. At any rate, as traditional woodsmen, we all need to be ever vigilant with each detail and circumstance of our historical simulations. We are human, and we make mistakes, and with that in mind, I think it is important for every living historian, every traditional hunter, to keep safety first and foremost, at all times, not just when we are immersed in a wondrous 18th-century adventure.

Perhaps age brought Browning to the error of his youthful ways when he wrote:

“I know now, and I knew then, that there was great danger in doing so, but if I undertook anything, I thought it must be accomplished; and if I got into a dangerous scrape, the greater the danger appeared, the more anxious I was to win the fight.” (Ibid, 180)

Think before you act, be safe and may God bless you.

One Response to My Mouth Grew Dry