“Jay!”

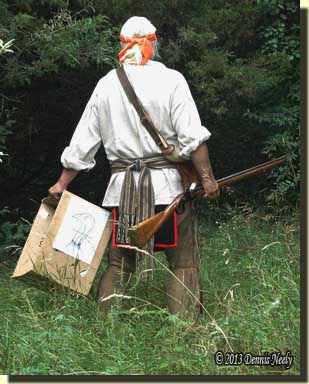

The blue jay cried out but once. The alarm seemed halfhearted and without authority. After a pause, my elk moccasins whispered along the familiar trail. The blue jay watched. The empty Northwest gun hung heavy in my right hand. A cool breeze whispered in the tops of the cedar trees, sounding like a gentle gasp of unexpected delight. I paused at the fallen cedar tree, just as I had on that gray morning, back in December of 1795.

On that day, barren branches made the course easy, but now a sea of green leaves flittered, obscuring the path to the oak where the grape vine grew. As I crested the little knoll, a cedar tree’s dead branch scratched across the cardboard box I carried in my left hand. A skeleton-like twig grasped the open side, tugging it back. I stopped, not wishing to tear the precious target.

On that day, barren branches made the course easy, but now a sea of green leaves flittered, obscuring the path to the oak where the grape vine grew. As I crested the little knoll, a cedar tree’s dead branch scratched across the cardboard box I carried in my left hand. A skeleton-like twig grasped the open side, tugging it back. I stopped, not wishing to tear the precious target.

As I unhooked the twig, I realized I was rushing. My mind had filled with the excitement of that morning. The rhythmic clucking of wild turkeys echoed in my subconscious. The same tingle ran up my spine and tweaked my neck hairs. I remembered the two crisp “arks,” and the unmistakable thrashing of big wings leaving the roost. As I stood beside the oak, I relived the young hen’s swooping descent as it winged across the big swamp and thumped into the leaves, fifteen or so paces to the north.

I have no idea how many spring and fall turkey seasons I sat and dreamed about a roosted bird taking flight and landing within “Old Turkey Feathers’” effective range. Time and time again, in my mind’s eye at least, I was up to the challenge, mounting the smooth-bored firelock and unleashing the death bees with the skill and efficiency of Josiah Hunt or John Tanner or Meshach Browning. But when the moment of truth came, a hefty splash of cold water washed away those follies.

Fancy Meets Reality

On that morning, the Northwest gun held a single death sphere, not the bees, and turkey season had come and gone a month before. With the frizzen up and the hammer down, I remembered rolling the trade gun to scatter the pan’s gunpowder—legally unloading the piece. By then, the turtle sight was easing toward the hen’s eye, but she caught the motion and ran uphill. The harsh failure in that fleeting pristine moment proved a bitter pill.

For me, the wilderness classroom is always in session. The brass lead holder scribbled a loose account of the happening as I leaned back against the oak and sulked. I couldn’t believe it when I heard another string of “arks” coming from the same tree where the hen once roosted. I don’t even remember dropping the leather envelope that holds the journal pages or the porta-crayon. The hammer was down, the pan dumped and the butt stock was halfway to my shoulder before the jake took wing.

The turtle sight caught him as he flew straight at me. The bronze streak banked left. I remember my mind yelling “NOW!” as the jake coasted from behind a cedar tree. I honestly believe I could have made that shot with a round ball. It wasn’t the first time I have been in that situation. In the past, I have wrestled with finding a way to duplicate such a situation, to test if the 18th-century me is truly capable of making that shot, but I have never come up with a safe alternative. On that morning, it didn’t matter.

The jake landed a few paces closer than the hen, and like the hen, he stretched his neck high. I recall having time to line up the turtle sight with the tang screw, and in a second the voice in my head yelled “NOW!” The unsuspecting wild turkey took two steps, then paused and looked uphill. “NOW!” After a couple more steps a bird putted uphill. The jake froze. The turtle sight dallied on his eye before the voice unleashed the third and final death sphere. I swear I could smell burnt gunpowder and see the white smoke drift over where that jake once stood.

Fulfilling a Promise

Quiet reflection filled the days that followed. A lingering curiosity kept prodding and I spent a lot of time thinking about Meshach Browning’s wife Mary asking him “to bring home some young turkeys for supper” when her eldest sister came to visit:

“Into the glades I went, where I soon saw three or four old turkeys, with perhaps thirty or forty young ones. I sent Watch [his dog] after them, but they flew into the low white-oak trees; and when I would walk fast, as if I was going past them, they would sit as still as they could, for me to pass on; but after walking twelve or fifteen steps, I would stop and shoot off their heads. I thus kept on till I had shot off the heads of nine young turkeys… (Browning, 122)

The first hen provided a valuable lesson in the wilderness classroom. Thinking through the situation, a body shot was the only reasonable possibility, if such a choice were legal under modern game regulations. But keeping in character, that course was bound to damage valuable table fare, which is why Browning took head shots. In hindsight, the importance of the hen rested in the sequence of calls that preceded the fly down.

The jake represented a second chance. For once, I learned from the hen and was better prepared when I heard those two sharp clucks. Legally unloaded and up, my mind chose a wing shot first. After landing, the jake had nary an inkling of my alter ego’s presence, because there was no barrel swing to detect; the turtle sight had a firm grasp of his eye.

In the next four or so steps the unknowing youngster afforded not one, but three opportunities for the historical me to feed my family in the manner of Meshach Browning. Before deer season ended, I promised myself I would return with a turkey-head target and answer the pesky “what if” question: “Could I make the head shots with ‘Old Turkey Feathers?’”

Where I sat that morning is a bit remote. Dragging a portable target frame up and down the east slope of the big ridge is not a good choice, and certainly not necessary for what I had in mind. A small cardboard box with a life-sized, turkey head target stapled on one side would serve just fine. At the last minute, I decided to set the box in line with where the jake stood, but at the hen’s distance. I reasoned I might as well find out if I could make the shot on both birds.

After loading, I sat and took aim, but the thrill of that pristine moment proved lacking, the shot too easy, too much like target shooting at the range. I let the Northwest gun down, closed my eyes and remembered the two clucks. I intentionally increased my breathing. When I heard the wings flap, instead of dumping the pan, I shouldered the gun and swung on the imaginary jake as it cleared the cedar tree. It took three tries to bring my heart rate up, to simulate that 18th-century instant. On the fourth try, the turtle sight caught the jake’s eye. My arteries pulsed. As on that morning I took quick aim, long enough to be aware of aligning the sights.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

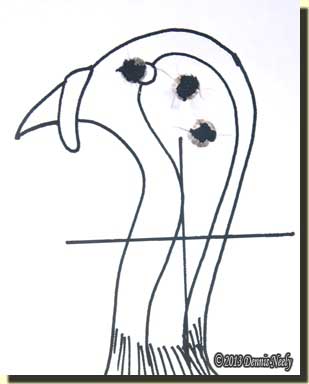

I smelled the joyous stench of spent gunpowder, for real this time. Letting the smoothbore down a tad, I peered through the white, roiling smoke. The death sphere left a black hole in front of the jake’s eye. My left hand exhibited a noticeable tremor as I dumped another charge of powder down the barrel. I kept breathing shallow, duplicating the exhilaration I felt last fall after the death bees swarmed about a fine wild turkey. Not wishing to lose the emotion of the moment, I sat, closed my eyes and swung again. The turtle sight clawed at the gaping hole in front of the jake’s eye .

I smelled the joyous stench of spent gunpowder, for real this time. Letting the smoothbore down a tad, I peered through the white, roiling smoke. The death sphere left a black hole in front of the jake’s eye. My left hand exhibited a noticeable tremor as I dumped another charge of powder down the barrel. I kept breathing shallow, duplicating the exhilaration I felt last fall after the death bees swarmed about a fine wild turkey. Not wishing to lose the emotion of the moment, I sat, closed my eyes and swung again. The turtle sight clawed at the gaping hole in front of the jake’s eye .

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!” The blast echoed up and down the big swamp. I think a blue jay started screaming up the hill. I realized I was breathing harder, perhaps from the induced excitement, but I think more from the fact that the second hole, at the base of the jake’s skull, shouted that I almost missed. I fought the urge to settle myself down as the wiping stick rammed the third lead ball firm. I dropped to my seat and again heard the thrashing, rhythmic wing beats.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

On a pleasant August afternoon, back in December of 1795, a thick white smoke hung heavy over the spot where a young wild turkey once landed. The lingering “what if” question of that 18th-century circumstance found an answer: the jake died thrice.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

One Response to The Jake Died Thrice