Pre-dawn’s silence stoked anticipation’s fire. Fading stars spawned an age-old wanderlust. In the graying darkness, silver dew drops clung to every grass blade, every bough tip, every greening stem. The air smelled clean and fresh, laced with a hint of rotting deer pellets. Elk moccasins splashed, driven by boyish glee; buckskin leggins swooshed. On that May morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1792, the woodsman’s course pushed ‘round the bend, crossed into the dip and ascended the steep trail to the ridge’s crest.

Crows, cardinals and chickadees delivered the first sounds of the new day. “Aww, coo, coo, coo.” A mourning dove cooed, somewhere in a cedar tree to my right. The dove’s haunting refrain cast an aura of doubt on my humble fort: four cedar trees that grew in a horseshoe-shaped clump. I heard not one wild turkey and began to wonder about the morning’s choice of lairs.

Then, in the distance, off to the east, I detected a series of faint “arks.” At that instant, a flock of song sparrows serenaded the makeshift fort, chipping away, hiding the hen’s yelp. As I strained to listen, the clucking grew louder; that bird was on the ground, advancing closer.

“Gob-obb…” A weak, half-gobble echoed in the hardwoods, three rolling knolls to the west.

“Ark, ark, ark, ark.”

“Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!” The tom answered quick, its intentions apparent. I rolled to my knees; my right hand pressed down on the Northwest gun’s forestock, holding the smoothbore’s butt firm to the ground. The hen responded with four more clucks, the tom with another long, forest-shattering warble that sent shivers up and down my spine. My mind charted each turkey’s probable course; I was certain the little clearing on the ridge crest was the rendezvous point.

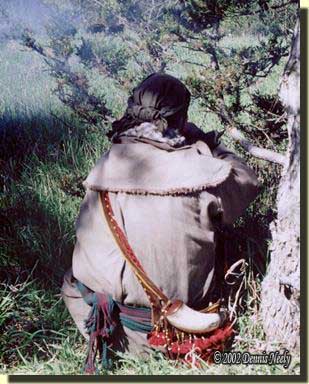

Moccasins thumped. Droplets sailed. Purple raspberry switches clawed. Arms churned. The flap and swish of the impetuous rush covered the clucks and gobbles. I stopped after about sixty strides, pressed my linen and leather clad shape into the boughs of a broad cedar tree and listened.

The hen was closest, on the path that skirted the big swamp’s east edge. Her boisterous clucking had turned to soft, spaced-out “putts,” uttered not in alarm, but rather to mark her progress.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl! Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!” The tom sounded a tad more worked up as he crested the second hill. I remained still, fighting the urge to move forward, not sure of where the two lovers might meet.

The hen putted once in the middle of the sedge grass. She had passed the longer trail at the north end of the little pond and had chosen the shorter path beside the spring, straight down the hill from where I stood.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl! Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!” The tom’s answer echoed through the hardwoods, and from the sound it was clear he was not going to follow the path that led through the valley.

My moccasins splashed ahead. The hen’s second putt from the west edge of the big swamp showed signs of hesitation. In an instant I decided to change fortresses. I gambled she would wait on him to strut and serenade her from the ridge top. I took refuge behind a spindly wisp of a cedar tree that grew off to the side of a grassy clearing, uphill from the tom’s last gobble.

My moccasins splashed ahead. The hen’s second putt from the west edge of the big swamp showed signs of hesitation. In an instant I decided to change fortresses. I gambled she would wait on him to strut and serenade her from the ridge top. I took refuge behind a spindly wisp of a cedar tree that grew off to the side of a grassy clearing, uphill from the tom’s last gobble.

Dew soaked through the seat of my drop-front trousers as I threaded the Northwest gun’s muzzle through the skimpy branches. My thumb pushed the frizzen forward; the pan’s prime met with satisfaction. The English flint clicked to attention. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, Oh Lord,” I prayed in haste.

A Comparison of Impressions

I started this post before Thanksgiving. Being addicted to traditional black powder hunting I spent the weekend in the woods as a returned white captive hunting white-tailed deer, instead of writing. I haven’t put hunting first in several years, and it felt quite refreshing.

Last Tuesday morning’s still-hunt paused behind that scrawny cedar tree. It’s a lot taller now and more filled out—time marching on, and all. That tree, coupled with Thanksgiving being two days away, brought to mind the excitement that surrounded that May turkey hunt, so many years ago. Curiosity got the best of me. When I returned home, I pulled out the photo album that holds the pictures from that morning. The cedar was a lot smaller back then. “Different” is the word I often use for such circumstances.

But the comparison went beyond just the cedar tree. As I leafed through the pages, I could see the progression of my trading-post-hunter persona over time. Like the cedar tree, I have grown. I am different, too.

I mentally started listing the changes—some were obvious, others hidden from sight. Again, out of curiosity, I skipped ahead a decade or so to last fall’s turkey hunt, the last time my trading-post-hunter alter ego killed a wild turkey. I began comparing the two images.

Both photos show a living historian attempting to put forth a truthful representation of a traditional woodsman from the 1790s, but the impressions are different. The Northwest gun, the powder horn (less the beaded strap), and the leather leggins are all that remain of the former historical me. The rest of the clothing and accoutrements have been replaced over time, but this is the normal progression of knowledge that typifies this joyous pastime.

The Power of a Photograph

A traditional black powder hunt is a solitary endeavor, and on occasion several like-minded traditionalists might camp or hunt together. But when talking with other traditional hunters, I find few who take pictures of themselves. A camera is rarely packed; it is simply not period-correct. In the last year or so, I have come to realize I am an exception, because images are a necessary part of the writing profession, an effective tool for spreading the word about traditional hunting.

Most living historians base their persona on a prudent mix of primary documentation, existing historical artifacts and paintings or illustrations created by first-person observers of a past time period. For me, the highlight of this fall’s hunting is a new persona based on the captive narratives of John Tanner, Jonathan Alder, O. M. Spencer and a host of others.

After two months of hard hunting, I already look at the photos of my returned captive persona and shudder at the errors. I’m embarrassed for publishing some of the images, but I do so with the hope others will learn from my first-hand experiences in the wilderness classroom. The impression will never be perfect, but like moving up on the tom, seeking refuge behind that pitiful cedar and anticipating a wild turkey’s approach, I hunted with the best understanding I had. I entered the glade, ventured into the past and I hunted.

As with all living history, the goal is to edge closer to perfection, knowing every historical simulation will fall short of “exactly right.” With that goal in mind, my recent research has focused on illustrations, paintings and etchings of Ojibwa and Potawatomi peoples from the 18th-century’s last decade. Without thinking about it, I have been comparing this fall’s photos with those historical images, thus my disappointment with my current impression.

Until this week, I never realized how helpful a photograph of my persona, taken under field conditions, was. I have made such comparisons for a long time, but never with conscious awareness of the value of the practice. As a result, I would like to urge all traditional hunters to start accumulating photos of their alter egos, if for no other reason than as a learning tool for perfecting one’s persona.

A digital camera and a small, table-top tripod can be stowed out of sight in a hand-sewn linen pouch. The “ball pivot mount” allows for portrait or landscape picture orientation. The 5-inch tall tripod features legs telescoping 8-inch legs.

Most of today’s digital cameras have a “timed-delay” feature. A stump, a downed log, an improvised crib of sticks or a re-purposed haversack can provide suitable support for the camera. I usually pick a spot, lean the trade gun against a tree and then focus the camera on the trade gun. In my case, I use a larger camera with a remote control to activate the time-delayed shutter. And the easiest method is to ask a hunting companion to snap a few pictures, or have a family member tag along on a short scout.

Once the image is created, print it out or store it electronically for future reference. Almost every family has a photo expert, adept at cropping and enhancing a digital photo, most often for posting on social media. Ask for that person’s assistance. The basic skills are not that hard to master. The benefits are tremendous.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl! Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!” My left elbow pressed hard against my raised knee. The turtle sight lingered in the area of the doe trail that emerged from the cedar trees. I saw the tom’s white pate first. The gobbler took three bold steps, never pausing to survey the clearing for danger. He fanned his tail. His flowing black beard dragged in the wet grass. He tipped his head back and opened his beak. “Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!” His whole body shook.

The turtle sight caught his eye. The flint lunged. Sparks flew. Gunpowder flashed.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

The big gobbler rolled backwards and flapped his wings. I pushed myself up and ran to the downed turkey with long strides. My moccasins anchored his legs, but that was not necessary. I knelt and gave thanks for the blessing of the morning.

Snap a photo of your persona, be safe and may God bless you.