Bright green flesh fell. A tree frog landed on its back, splashing in the tiny puddle gathered in a cupped white oak leaf. The interloper squirmed and twitched, stretched and flexed before its left hind leg pushed it over. Rain dripped from cedar bough tips. The mystic visitor sat still, as did an amused Msko-waagosh, the returned white captive who subsisted beside the headwaters of the River Raisin in the Old Northwest Territory.

Two cedar trees distant, a cottontail rabbit remained sequestered in a thick, whiskey-keg sized tangle of raspberry switches that did not belong in that part of the woods. Its long ears rested against its neck. A large brown eye probed the woodsman’s measured moves, but found nothing of concern. After all, it chose its morning shelter at first light, just after the hunter settled under the broad cedar partway up the hillside.

“Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark.” A hen turkey called in the vicinity of the large oak, forty paces uphill from the murky water in the northeast corner of the nasty thicket. The tree frog hopped twice, then scooched under a winter-weathered oak leaf.

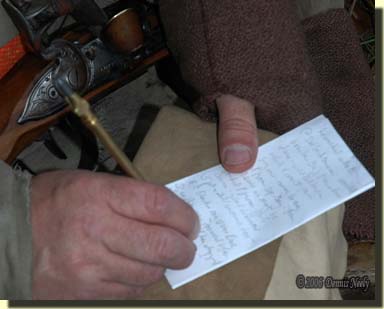

Cautious fingers folded the split pouch up, retrieved the tarnished brass lead holder, a folded piece of parchment, then returned the pouch to its original position. The burning desire to record the epic of the rabbit and the tree frog weighed equal against the necessity of bringing a wild fowl back to camp.

Lead scribbled. Words strung into phrases. Pages filled. Wispy blue patches appeared beyond thinning clouds. The time came to refold the paper. The rabbit’s ears rose up. Fleeting glimpses of bronze herky-jerked along a far-off doe trail. The lead grew blunt.

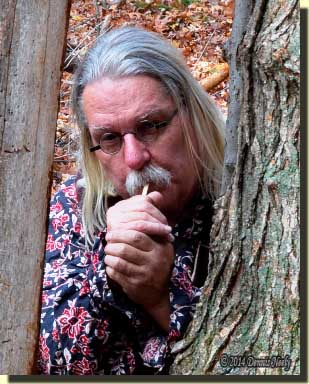

Before dropping his wool bedroll against the cedar trunk, the woodsman brushed away the duff with his moccasin toe. He noted a small gray rock that rolled over in the dead cedar needles. Now, almost two hours later, he laid the lead holder on his breechclout’s front flap. With a minimum of movement, fingers sifted through the duff pile until they found the rock.

The blunt lead point moved side-to-side on a flat facet as his fingers rolled the lead holder’s brass barrel. A dozen or so rubbings re-sharpened the tip. Satisfied, he placed the rock, black smudge up, back on the duff, within easy reach in case he needed it again.

Through all this woodland commotion, the rabbit sat tight. When Msko-waagosh turned the page to continue recording the day’s adventure, the rabbit’s ears sprung to attention. It took a hop, stopped, then stretched before taking several bounds downhill to a winter-downed oak limb. It pause, inspected the hunter who was captured in his youth and raised by an adoptive Ojibwe family, then took a long leap and disappeared in the darkness beneath the limb.

A female cardinal winged to a cedar branch two trade-gun’s length above the woodsman’s lair. It chirped once, took a quick look about then flitted off uphill.

“…nothing unusual after the she-cardinal left…” was the last phrase on the journal page for that fine May morn in the Year of our Lord, 1794.

Scribblings of Interest

Writing possesses a soothing, spiritual quality, at least for me. Rare is the time-traveling adventure that does not include a few moments of scribbling, either personal thoughts or the circumstances of the day. Some days the mere act of pulling out the lead holder and folded pages attracts wild game. Perhaps that is superstition and perhaps not…

About four Decembers ago, Msko-waagosh sat in a favored tree top uphill from a monarch red oak. Deer trails passed below that lair. On that cold, snowy Sunday morning four or five hen turkeys pecked along the earthen pathway that followed the edge of the big swamp. Nothing else moved about, other than one gray squirrel.

Once the birds were out of sight, chilly fingers tugged the lead holder and paper from the split pouch, just as they did on that fine May morning. Three sentences later, a jerky step, then a bronze-feathered body entered the woodsman’s left periphery. The scrawling ceased and squinting started.

Four plump gobblers, each sporting a beard that dragged in the light dusting of snow, made their way south in front of that tree top. As so often happens, wild game appeared within minutes of deciding to start writing.

The birds circled the lower branch that lay across their path. The largest one, which was the third in line, marched up to that branch, three trade-gun lengths from the returned white captive, wrapped in a crimson trade blanket. Ten minutes of peering ended when the four walked off. Needless to say, the sharp lead filled four folded pages in a hurry. No superstition or magic about it; pull out the journal and game will wander by.

Traditional black powder hunting involves more than changing clothes and striking off into the forest carrying a firelock. One must develop a mental attitude that sets “what is” aside and replaces the here-and-now with “what was.” Beyond that mindset is a deep desire to become one with the 1790s, in the case of Msko-waagosh and the hired post hunter, to become a “…tenant of his forest,” as Joseph Doddridge put it (Doddridge, 101). A part of developing that woodland skill set is learning how to write without attracting the attention of the other tenants.

About three decades ago, I began folding paper in half, then the folded half into thirds. That method allowed for easy stowing of the “journal page,” without lugging along the bulk of a leather-bound volume. A side effect of that habit is that the page becomes twelve individual pages. When the first six are filled, the paper is unfolded, then refolded so the back becomes six blank pages.

I find that my alter egos are most vulnerable when the unfolding, refolding takes place. And so it was with the cottontail rabbit. Despite hiding the process from its view, the muffled crackling sounds caught its attention. In essence, such sounds do not belong in its wilderness world.

Years after “discovering” this journal method, Mark R. Tully wrote about the folding of paper to form the British “returns,” which recorded the daily soldering business of a Red Coat garrison. The paper sheets were larger, half folded, then quarter folded, but the need was the same: reducing a larger sheet to manageable size for ease of writing, transport and storage (Tully, The Packet, 16).

The creation of a third character, Mi-ki-naak, the Snapping Turtle, affords three different possibilities for journaling. The assumption is that each character has a rudimentary grasp of reading and writing English, which was not the case with John Tanner, who is the major inspiration for Msko-waagosh.

The narrative of Charles Johnston’s captivity addresses the “imperfect” state of trying to record one’s life experiences during a harrowing time. According to his journal, Johnston used a copy of The Debates of the Convention of Virginia, making notes in the margins and white spaces of the printed page. He fashioned a pen from a wild turkey quill with a scalping knife, and made ink by “mixing water and coal dust together” (Johnston, 58 – 59).

The quill and ink is suitable for writing around a camp fire, but I found it untenable for “in the moment” woodland circumstances. I have a portable, tin inkwell, but it simply does not lend itself to my style of hunting.

The brass lead holder fits the hired trading post hunter, but is a bit extravagant for the returned captives. I do not find paper listed in the trading post inventories; likewise entries or mention of purchasing paper with peltry. Thus the use of the folded blank page is a stretch, because where would each of these characters acquire the paper? “Oh, just a second, I have to go into my wigwam and gather more papers from the ream,” does not hold water in an 18th-century wilderness sense.

The doctrine of “measured compromise” eases over such anomalies, just as it wills away the crushed pop can along the trail or the incessant beeping of a garbage truck’s back-up alarm in the distant village. That said, the journaling system works for me. The unfolded pages fit in file folders, identified as either “spring” or “fall” with the year noted, and provide the basis for retelling the tale of the tree frog and cottontail rabbit, recorded on that fine May morn.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

One Response to That Fine May Morn…