One-by-one, five blue jays hollered. A chipping sparrow bobbed up-and-down on an autumn olive sprig. Its beak opened, but the blue-jay ruckus overpowered this tiny, forest tenant’s “chip, chip, chip, chip, chip…”

The constant “JAY! JAY! JAY! JAY! JAY!” intensified as two of the sentinels flew closer. Such was the commotion of that October afternoon, in the Year of our Lord, 1795.

Seven Canada geese winged from the southeast. The lead bird began a steady “Kehonk, kehonk, yonk, yonk, kehonk,” over the neighbor’s threshed wheat field about the same time the blue jays struck up their chorus. The small wedge passed low over the tips of the tall cedar trees on the ridge crest, and once well to the west, those birds returned to silent flight. The blue jays fell quiet, too.

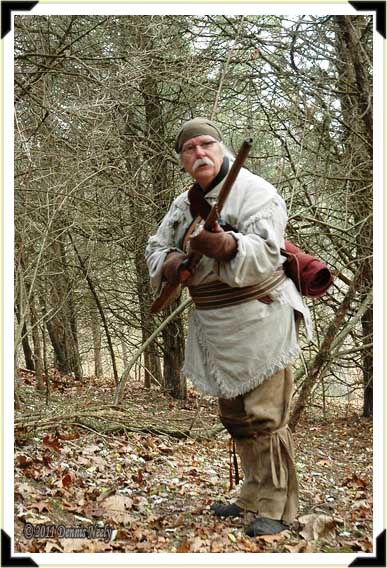

The glade returned to a melancholy state of dismal. Perhaps the thick, steel-gray clouds set that tone; perhaps it was the sticky humidity of an impending downpour. The air smelled damp and heavy, almost stifling. The aroma of fallen oak leaves permeated the hillside. A light breeze pushed a woodsman’s long gray rat tails against a sensitive cheek, irritating with a tickle.

In time, a red squirrel raced along the lowest branch of a spreading red oak at the edge of the big swamp. It squeaked twice, slowed its pace, then squeaked in a steady chatter as it lingered at the outer tip of the branch. A second red squirrel answered, up the hill a bit, somewhere within the shadows of a red cedar tree.

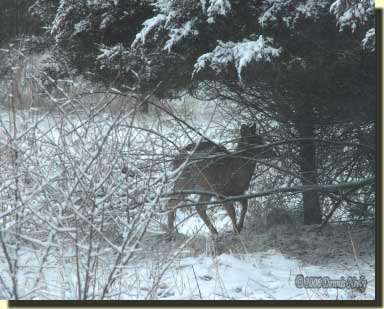

Leaves rustled to the north, more muffled than loud, in the area of a giant, hollow red oak. The disturbance stopped, then began again with a discernable cadence. A plump fox squirrel bounded down the hill, angled along a barkless tree trunk, then scampered behind a smaller oak. Geese kehonked to the north, but slipped into obscurity.

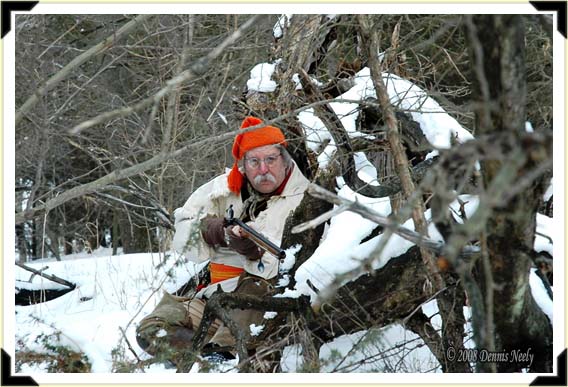

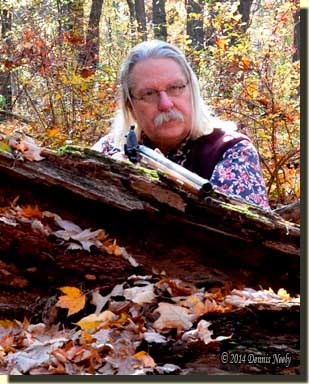

A two years before, a violent spring storm wrenched three oak limbs from a tall trunk and threw them to the earth in the same spot, halfway down the hill’s steep east slope. The tangle of branches offered ample fortification for an ambush. Wild turkeys were the favored dinner fare, but squirrel would do, if such a creature ventured within the grasp of the death bees. Forty paces was just too far.

A two years before, a violent spring storm wrenched three oak limbs from a tall trunk and threw them to the earth in the same spot, halfway down the hill’s steep east slope. The tangle of branches offered ample fortification for an ambush. Wild turkeys were the favored dinner fare, but squirrel would do, if such a creature ventured within the grasp of the death bees. Forty paces was just too far.

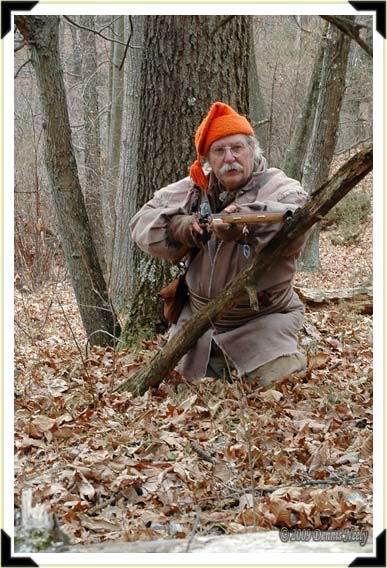

With care, nimble fingers retrieved a silk scarf, rolled it and tied it about the woodsman’s long gray hair, changing the complexion of that simple pursuit. The Northwest gun’s turtle sight eased along a moss-covered branch. The fox squirrel was the most opportune choice for a quick evening meal.

Two blue jays swooped low, rose up and perched in the giant, hollow oak. One looked to the north, the other to the south. In a few dozen heartbeats, the closer jay moved its feet, then turned its gaze uphill; the other did the same woodland dance, then surveyed downhill in the direction of the big swamp. Neither bird uttered the anticipated alarm. The one blue jay flew east, the other west.

The westerly bird swerved around a small maple with deep-red leaves. A fox squirrel ran from behind that tree, thirty paces distant. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” Msko-waagosh, the returned white captive, whispered…

An Unforgivable Step Backward

Some mornings blue jays take center stage in the wilderness theatre, other days it is the cardinals, crows, geese or perhaps frolicking squirrels that get top billing. The bit characters in any traditional black powder hunter’s saga are just as important, if not more so, as the primary game of that day and time.

Wild turkeys and white-tailed deer are the stars of today’s outdoor extravaganzas. Little mention is given to “small game” anymore.

I watched an interview of an “outdoor celebrity” a while ago. His focus is monster deer. When asked if he hunted other game, his response was why waste your time with a single meal when you can fill your freezer with venison. Of course, his money comes from his deer-hunting videos, shot all over North America, and the commercial endorsements they produced. I suppose that would be the same as an auto worker riding a bicycle to work; shot-in-the-foot wounds bleed the same.

To be fair, in the last thirty years or so, I have passed on a number of smaller bucks. ‘Antlers out to the ears and eight points’ is the rule on the North-Forty, unless you are a first time hunter who has never taken a deer or the deer is wounded or injured and not expected to survive the winter.

Such restrictions represent a wildlife management decision that started when heavy modern hunting pressure impacted the deer’s breeding cycle. An out-of-balance buck to doe ratio contributed to those decisions, as did the devastation from epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD). The North-Forty’s carrying capacity and other environmental issues factor in, too.

These self-imposed parameters run contrary to the woodland practices my hunter heroes wrote about. For the living historian, measured compromise smooths over the inconsistencies of “what is” versus “what was,” but John Tanner would not have approved.

In a similar manner, the hunter orange requirement affects traditional hunters on the modern stage that hosts their productions. Measured compromise smooths that intrusion as well. As a result, for most outings Msko-waagosh carries both a hunter orange and a black silk scarf—his trading post hunter counterpart does the same. Thus, on that evening, the emphasis changed from a big upland bird to small game—the fox squirrel, which required hunter orange.

For me and my alter egos, the longer season allotted to small game transforms a deer or turkey scout into an 18th-century adventure. I started my hunting career on small game, and I have no intention of forsaking the simple pursuit of the lesser forest creatures—and along with that commitment comes a dedication for their well-being and preservation.

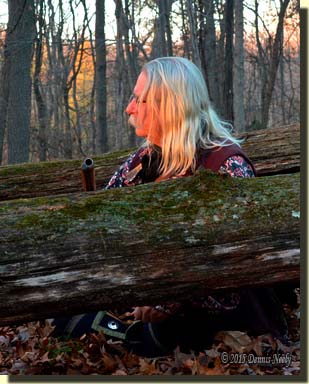

This past fall I made a conscious choice to give up hunting hard for a wild turkey, then a buck deer. Instead, I spent time afield with the first of my grandchildren to take up hunting and the shooting sports. It was not easy working around after-school activities, but we did. I had one of the best hunting seasons ever—despite sitting next to a time traveler from the 21st century.

Freezes and thaws, too much snow or too much mud, have kept us out of the “winter woods,” but there is still time to enjoy a squirrel and/or rabbit hunt or two. Just as when I grew up, the skills necessary for success in any woodland chase come from hunting small game first.

Time and again I encourage newcomers to traditional black powder hunting to start with small game hunting and use that experience as a stepping stone into this glorious pastime. The modern hunting videos and advertising propaganda run counter to that advice and spill over into our outdoor genre.

Back in late-September, I had a long telephone conversation with a gentleman who purchased a used English fowler in 20 gauge. He understood the basics of nurturing the flint ignition system, of developing an effective load and of caring for his new smoothbore. When he talked about “waiting for deer season,” I urged him to start with small game. He said he hadn’t hunted small game in years.

A couple of weeks later he emailed a photo of a gray squirrel next to his fowler. Sometime later images of more table fare from another squirrel hunt arrived, then came his first wild turkey with the fowler, followed by a fine young buck. In the messages that accompanied the turkey and deer, he spoke of how he gained confidence in the fowler through squirrel hunting and how he believed that experience carried over to the fall hen and the buck.

For many people, especially those influenced by the dogma of today’s high-tech revelations, traditional black powder hunting is an unforgivable step backward. When veteran living historians tout the fair-chase pursuit of the smallest of the forest tenants, the advice is tantamount to hunting heresy. But when the hand wrenching subsides, there is no arguing with the wisdom of long ago…

The Northwest gun stalked south along the moss-covered branch. The tarnished-brass butt plate pressed against the woodsman’s shoulder as the turtle sight continued the uphill journey, slow and deliberate. Likewise, the fox squirrel journeyed downhill, circling closer and closer to the fort’s tangled palisades. The trade gun’s muzzle met the backcountry hunter’s evening morsel at twenty paces. The turtle sight clutched the squirrel’s eye and never let go.

The Northwest gun stalked south along the moss-covered branch. The tarnished-brass butt plate pressed against the woodsman’s shoulder as the turtle sight continued the uphill journey, slow and deliberate. Likewise, the fox squirrel journeyed downhill, circling closer and closer to the fort’s tangled palisades. The trade gun’s muzzle met the backcountry hunter’s evening morsel at twenty paces. The turtle sight clutched the squirrel’s eye and never let go.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

Yellow and orange fire erupted. A joyous, sulfurous, white stench surrounded the twisted branches. The death bees swarmed. There was no escape for the fox squirrel.

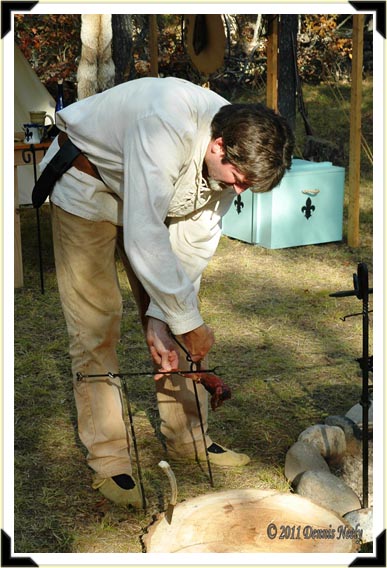

The smoothbore’s warm muzzle end did a turnabout; the butt stock settled against the ground under a lower branch. Gunpowder cascaded into a pile in the woodsman’s palm, then sifted into the gun’s open bore. Two wadded oak leaves, minus their stiff stems, followed the charge, thumped firm by the hickory wiping stick. A new clutch of anxious bees rattled after. Another balled-up oak leaf, packed tight, finished the load.

Primed and ready, Msko-waagosh, the Red Fox, scrambled to his feet, looked about and stepped to the dead squirrel. “Thank you Lord for the blessing of this meal and the blessings of this day…”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.