Seventeen wood ducks winged low. Lavender and orange backlit a dark tree line as the three groups pulsed back and forth to the southeast. Two stragglers flew overhead, just beyond the Northwest gun’s effective distance. Oak leaves took no notice, the air being breathless calm with a dewy, somewhat dusty, fragrance.

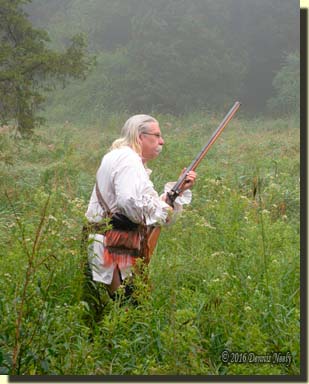

Light oil coated the trade gun’s bore. The death bees slept in a stoppered, palm-sized leather bag in the Ottawa-style shot pouch that pressed a discolored ruffled shirt snug to the woodsman’s right ribs. Seven round balls huddled in the pouch’s bottom seam. It was, after all, the last week of August in the Year of our Lord, 1796.

A pause in the sojourn, down the hill and around the bend, revealed three distinct tracks left in the washed sand by aged elk moccasins. The left print showed the oblong hole worn in the sole. Msko-waagosh stepped off the path, picked up an oak twig, a blow-down that possessed wilted leaves, and erased all evidence of his passage. The morning’s scout continued, but with greater woodland stealth.

Eighty paces down the ridge to the north, the woodsman, schooled by the Ojibwe in his youth, came upon a small, skinny white tail, twitching from side to side, no more than twenty paces to the east. A spotted fawn stood half-hidden amongst some autumn olive sprouts. Facing away, this forest nymph knew not of a humble returned white captive’s approach.

A second, older tail flipped side-to-side just over the rise, behind two scraggly red cedar trees. The second fawn’s head, maybe ten paces beyond the doe, popped up, glanced about, then dropped into the grassy patch that garnered its immediate attention. The encounter turned into a joust of sorts, wilderness tenant against wilderness tenant.

With all heads down, I grounded the Northwest gun’s tarnished-brass butt plate in the weathered leaves, gripped the muzzle with both hands and relaxed with my left shoulder against a modest oak’s rough bark

The closest fawn browsed its way around the base of a large cedar tree, angling a bit to the south towards its mother. It raised its head five times, flipping its ears and surveying the hill before it. Never once did it check its back trail. The matriarch’s head rose and fell as many times, too. The boughs of the scraggly cedars offered enough protection to block the doe’s view to the ridge crest.

The fawn took four or five steps across the hillside, as if it wanted to join its sibling. Then it weaved east, completed a tight j-hook loop and faced square uphill. Its head dropped, ears alert and eyes intent on the discolored ruffled trade shirt that glowed in the morning’s bright sunlight.

The fawn took four or five steps across the hillside, as if it wanted to join its sibling. Then it weaved east, completed a tight j-hook loop and faced square uphill. Its head dropped, ears alert and eyes intent on the discolored ruffled trade shirt that glowed in the morning’s bright sunlight.

A shiny-black front hoof rose and fell with no discernible noise. The older doe perked up. The fawn’s tail moved straight up, slow and easy. The mother looked uphill, then her head rose to attention. The second fawn paid no mind. I squinted, trying to avoid direct eye contact. Heartbeats began ticking away on both sides of the ridge.

The fawn took two steps forward. The doe looked at the fawn, then back to the wool and linen clad shape. Two more inquisitive steps…a long pause…then two more. A cloud’s shadow ran up the slope, crossed the ridge and jogged off through the hardwoods. The young doe, now no more than fifteen paces distant, jerked her head to the south, to the north, then down knee-high, all the while watching for a reaction. I found it hard to stifle a smile.

Sands sifted through the 18th-century hourglass. The old doe flipped her tail, then brought her nose close to ground level, still eying the oak. In a short while, she turned away and took several steps, joining the second fawn. She nudged that fawn. The first fawn turned its head and looked at its mother. Its left hoof stepped to the side. Then the fawn took three high bounds. A few minutes later the joust was over, and the wilderness tenants continued on their separate ways…

Seeking the Unknown Re-enactment

Quite some time ago, another experienced traditional black powder hunter and I slipped into a rather deep philosophical discussion regarding living history. We were talking about organized battle re-enactments and the disconnect that seems to exist between authenticity in the camp setting as opposed to during the scripted battle proper. At one point, I stated, “For me, a re-enactment begins every time I take that first moccasin step into the woods.” The other morning’s short jaunt is a fine example.

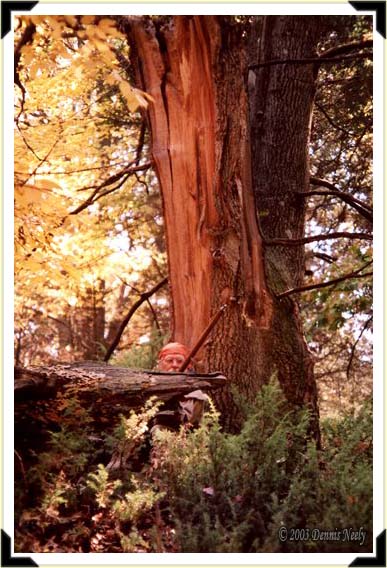

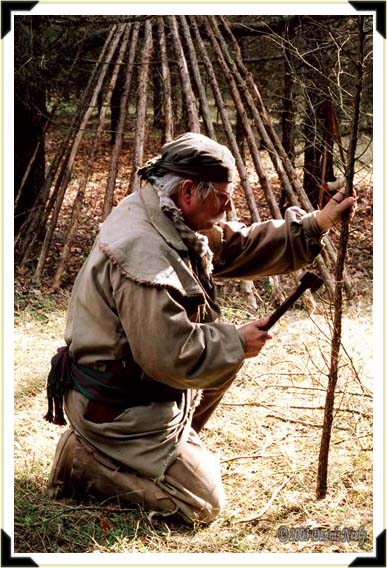

A recent windstorm toppled another red oak, maybe fifty paces from the wigwam. Oak trees are snapping off in the North-Forty with disturbing frequency. Three more have come down in the last six weeks alone. The object of that morning’s planned scout was a visit to the wigwam and further, the careful study of that broken oak—a 1790-flavored land management fact-finding excursion.

A recent windstorm toppled another red oak, maybe fifty paces from the wigwam. Oak trees are snapping off in the North-Forty with disturbing frequency. Three more have come down in the last six weeks alone. The object of that morning’s planned scout was a visit to the wigwam and further, the careful study of that broken oak—a 1790-flavored land management fact-finding excursion.

Depending on the scenario, I attempt to stalk a shelter in a period-correct manner, as if I was returning from a hunt. Despite the fact that “Old Turkey Feathers,” my Northwest trade gun, was unloaded, I still approached the scenario with a backwoods hunter’s mindset. The objective, the wigwam and the downed oak, was a mere suggestion, the course determined by wilderness happenstance within the framework of an historical simulation.

It took very few moccasin-falls to pass over time’s threshold. My woodland travel assumed the form of a slow and steady still-hunt, rather than a skipping and frolicking romp to an alter ego’s forest abode. While checking my back trail during the pause after reaching the sand wash, I saw my moccasin prints, which to Msko-waagosh is a huge no-no. The historical me remedied that situation, then spent a few minutes of soul searching and personal reflection.

The next eighty paces ate up many more of the proverbial hourglass sands than the first eighty, and there was nary a sign left along the way. In essence, the quality of that morning’s re-creation (or re-enactment, if you will) of a possible hour in John Tanner’s life approached a higher level of authenticity.

The reward for that conscious effort was a memorable encounter with a doe and two fawns that lasted almost twenty minutes and can be retold around any campfire, modern or traditional.

To me, the key is fostering a mental attitude that looks upon each moccasin step and its consequences or rewards as a living history re-enactment, as trivial or monumental as it may be. One of the major goals of this joyous endeavor we call traditional black powder hunting is to experience the texture of life in the past by pursuing moments in time when that past becomes real. For within such pristine moments are hidden that deep sense of kinship with our beloved hunter heroes that we all crave.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.