-

Recent Posts

Categories

Archives

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

Blogroll

Forums

General Living History

Historical Sites

Organizations

Artists

“Disappointed Voyageur”

Posted in Living History, Scenarios, Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “Disappointed Voyageur”

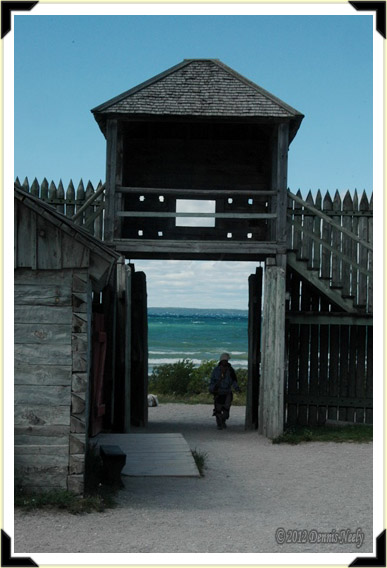

“Pigeon River Arrival”

“Snapshot Saturday”

Posted in Scouts, Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “Pigeon River Arrival”

A Structure for Learning

A readers note: This story deviates from my usual convention of warning you a kill is eminent with a “Kla-whoosh BOOM!” placed toward the end of the tale. As you will see, the nature of this story leaves no alternative…

A rifle boomed. The muzzle blast’s distinct sound bounced through the hardwoods. An unsettling silence produced a multitude of wilderness questions, most centered on a trading post hunter’s survival, in the Year of our Lord, 1794.

Minutes crept by, one ridge east of the River Raisin’s frigid headwaters. The air smelled crisp, not damp or storm-like, laced with a faint scent of churned earth from the nest scuffed out behind a hefty white oak. December’s few remaining songbirds kept quiet. Eight crows and three Canada geese winged over, but none uttered a note.

After an appropriate passage of time, I got to my feet, stretched, then slung the leather portage collar that bound my bedroll over my shoulders. Buffalo-hide moccasins struck off on a straight course, set on meeting up with the young man who sat over the ridge and down the hill amongst a clump of aromatic red cedar trees. Pausing beside a stout red oak, I realized he was no longer seated, his path littered with upturned leaves.

“BOOM!” That shot came from the north end of the nasty thicket, maybe a hundred yards ahead. Again, my moccasins whisked along, keeping high to the hill, avoiding any chance of crossing into a line of fire down in the thicket. “BOOM!” Another shot, this one more muffled than the second, told the story of a deer sequestered deep in the thicket.

Thirty or so paces down the trail, I again paused in plain sight, this time in front of an old cedar tree at the edge of a clearing. Wetting dry lips, I imitated the two-note whistle of a contented Bobwhite quail.

The young hunter stood in a thick patch of sedge grass, bent forward and peering into the brush. He turned, looked my way and pointed to the south. I signaled for him to stay put and sit. Knowing how visible I was, I retreated into the hardwoods and still-hunted tree-to-tree down to the protection of the trail that followed the thicket’s edge.

The young man pursued too soon after the shot, which was understandable. I did not want to make the situation worse, plus the longer I took reaching him, the better. When I came to a doe trail at the edge of a raspberry patch, I slipped into the thicket. Catching the frustrated hunter’s attention, I motioned for him to remain quiet, reach the trail and then come to me.

Once face-to-face, his hurried whispers told me the doe could not progress much farther. The main concern turned to improving our position and placing a humane final shot. To that end we circled southeast, hunched over and taking every advantage of the natural cover. The slow advance put us back on the edge trail, behind two oak trees, about twenty-eight paces from the bedded doe.

“You’ll have to sho ot her,” my woodland student said, “I lost my patches and I’m not loaded.” He was using a loaner rifle of mine, a reproduction .50-caliber Hawken rifle that shoots right on at seventy-five yards (despite my restrictions that the young man not take a shot over fifty). The rifle includes a small powder horn and a shot bag with ample round balls, patches, etc. I never did find his lost patches.

ot her,” my woodland student said, “I lost my patches and I’m not loaded.” He was using a loaner rifle of mine, a reproduction .50-caliber Hawken rifle that shoots right on at seventy-five yards (despite my restrictions that the young man not take a shot over fifty). The rifle includes a small powder horn and a shot bag with ample round balls, patches, etc. I never did find his lost patches.

“This is your deer. Measure powder and dump it down the bore,” I whispered as I pushed a frosty oak leaf out of the way and retrieved a drier leaf from underneath. I broke the stem from the leaf and rolled it into a wad.

“Ram this tight on the powder, then drop a ball down the bore and seat it on the wad,” I instructed as I tore another leaf in half and made a smaller wad. As he pulled the rammer out, I handed him the next wad. “Now slowly seat this on the ball to hold it in place, cap the nipple and take careful aim.”

The Debate on Deerskin Patching

A recent email exchange included a traditional hunter’s comment that “You have to patch a rifle ball. That’s just how rifling works.” In a follow up telephone conversation, I retold the above story, noting that the “BOOM!” was closer to a “CRACK!” with the wadding than with the usual greased patch, indicating a greater velocity. I suspect a chronograph would confirm that observation.

And true, on that December chase I turned the young man’s Hawken rifle into a smoothbore. The “right on” accuracy at seventy-five yards was in question, and no doubt not achievable. But the shot was twenty-eight paces, and the doe was put down with the same finality as a patched round ball. At the least, re-creating and studying this situation would make for a good wilderness classroom assignment.

Another wilderness classroom lesson that seems to be bubbling away in the forefront is the use of animal hide, specifically deerskin, for patching. John Curry’s recent article in Muzzle Blasts addressing deerskin for patching in rifles generated a number of inquiries asking about my opinion on the subject (Muzzle Blasts, June, 2016, NMLRA, Friendship, IN, pgs. 13 – 17).

I do not patronize Facebook; let’s just say I don’t agree with their “Terms and Conditions of Use” and leave it at that. But a hunting companion of mine has kept me abreast of other individuals’ social media posts regarding this subject, including those of Mike Beliveau.

My expertise regarding the use of natural materials for wadding in smoothbores is at the root of these requests. But I have not tested deerskin as a patching material in a rifle. I’m a passionate smoothbore shooter who occasionally shoots a rifle or pistol, if I’m forced to. And frankly, favoring a smooth-bored barrel, I don’t understand what the big fuss is about shooting a gun with a bore full of scratches…

Anyway, I’m not going to wade into this debate, per se, just as I would hope folks would not offer untested statements on natural wadding in smoothbores. That said, I find the topic of deerskin patching intriguing, and I feel there is value in viewing the learning process from a traditional hunters perspective with the ultimate result of someone who wants to take a deer, for example, using deerskin patching.

Expanding on the Wilderness Classroom Concept

As so often happens, an “I would be nice to know what they did” question arose in one of these telephone conversations. Without thinking, I reached behind the desk and pulled out a book of Audubon’s essays. I looked over the color-coded sticky notes, flipped open a page with a purple tab and began reading one possible answer to the caller’s query. Over the course of an hour’s conversation, I read aloud from five different authors as specific topics arose regarding primary documentation on the use of rifles by hunters in the backcountry.

As long-time readers know, I’m a strong proponent of traditional hunters viewing their 18th-century woodland Eden as a living, breathing wilderness classroom. This notion is not a whimsical or romantic fad that gives lip service to traipsing around the woods in a make-believe haze. Rather, the wilderness classroom is one potential tool at the living historian’s disposal for adding solid, fact-based knowledge and understanding to an authentic portrayal of a flesh-and-blood individual from long ago.

For me, the wilderness classroom offers an opportunity to outline a lesson based on a specific question and also provides a structure to go about seeking answers. The process I recommend is similar to the steps of the “scientific method” we learned in high school chemistry or physics classes.

First: The wilderness classroom methodology starts by defining a problem or asking a question. The big pitfall with defining the problem is starting with a question that is too broad, which results in too many possible laboratory experiments that produce conflicting or uninterpretable data. Instead of framing a question around using “animal hide,” one needs to be more specific and narrow the field to “brain-tanned deerskin,” for example.

The goal is to create a simple, one-sentence question that captures the essence of the issue. And during this first step, it sometimes becomes obvious that what one thinks is a good question is really two or more questions that must be addressed individually.

Second: The living historian must do research, seeking out primary sources—actual accounts, artifacts or sketches created by the people living the life—that contribute to a better understanding of the question or add background information. Once in a while the greater part of a question is answered by primary documentation. And on other occasions there is little guidance available in the recollections of our hunter heroes.

In the course of an hour, during the telephone conversation where I grabbed source material from my bookcase, we discussed about eight passages that significantly guided our thinking on the subject, and in essence, narrowed and better defined the question of using deerskin patching.

Now my intention is not to be critical, but as an outside observer to this debate, no one has put forth any primary documentation on the use of deerskin for patching. The premise that raised the initial question is based on the siege of Fort Harrod in 1777, which appears to be based on primary sources, but what are those sources, where can they be found, and what do they say?

Further, should not the point of beginning, at least for comparison sake, be what was used as “standard patching” in that era. From our discussions, one of the key starting points that came to light should be “What was the difference between bore size and the round ball cast by the mold supplied with the rifle?” Again, this is just an observation, but I offer it to emphasize the importance of researching a given question or issue.

Third: Based on available research, a hypothesis, or idea of what the answer might be, is formed. Now that hypothesis may be all wrong, or it may be real close to the answer. It is nothing more than a guess as to the answer.

And just like defining the question, the hypothesis should be simple and straight forward. It is not uncommon to come up with more than one hypothesis. When this happens the traditional hunter must decide if each hypothesis should be explored or if the question needs to be clarified. There is no right or wrong path at this point.

Fourth: Going hand-in-hand with this thought process, establishing the hypothesis allows the traditional woodsman to set up one or more experiments designed to test the validity of that hypothesis. Just as in defining the question, the experiment needs to be “tight” and undertaken in a manner that someone else can duplicate the test and achieve similar results.

In this case, significant range time offers the best platform for testing the validity of the hypothesis. One or maybe a series of experiments might be necessary, but it is important that only one variable is changed in the course of one test.

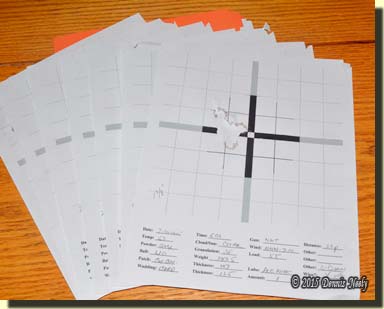

On the range, I use a “sighting in target” that is a simple darkened vertical and horizontal axis imposed over a one-inch grid. This target is eight inches square and prints on a standard sheet of computer paper. This size allows for the recording of pertinent information about the test at the bottom. I have eighteen standard items listed, plus room for “other” comments.

On the range, I use a “sighting in target” that is a simple darkened vertical and horizontal axis imposed over a one-inch grid. This target is eight inches square and prints on a standard sheet of computer paper. This size allows for the recording of pertinent information about the test at the bottom. I have eighteen standard items listed, plus room for “other” comments.

Again, I establish a process for range time, which includes circling the variable I change from target to target. And I only use one target per variable with a maximum of ten shots per target. I have seen several targets associated with testing deerskin patching, and I find it very confusing when a target shows fifteen or twenty hits that represent three or four variables.

Fifth: As the experiments unfold, the traditional hunter must keep accurate data of each test. This sounds more complicated than it is. For range tests, I keep a file folder for each hypothesis. The targets from one session get clipped together. If I shoot at 25 yards, those targets go together; I consider each distance as a “session.” I like to concentrate on shooting when at the range, so I often write out the steps for a given range session, nothing elaborate, just quick notes to jog my memory.

I leave the data analysis for a later time, but before the next range visit. I’ve found that even when an experiment is thought to be well-defined, issues crop up. Sometimes those issues require a separate set of tests. If that becomes the case, it is important to think through this change in course so that both the old test data and the new test data are usable.

An elaborate, statistical analysis is beyond my expertise. But I find simple tables or grids helpful, at least when looking at range data. Five 25 yard targets might give one impression, but when compared to five 50 yard targets, a different conclusion might be evident. And in the end, the experiment or experiments is only valid if someone else can duplicate the experiment with similar results. I cannot emphasize this point enough…

Sixth: Traditional hunters are a solitary lot; few think of “communicating their results.” I can’t begin to count the number of times I’ve sat in on a hunting discussion and heard someone share a tidbit of woodland wisdom or shooting savvy based on years of experience. If you’ve been a traditional hunter for a while, you’ve been in that position.

Elevating such comments to the “wisdom” level comes when one duplicates the situation and the resulting data matches. The problem is sifting out statements based on thorough and objective testing and a hypothesis that was never tested in the wilderness classroom, because the latter is pure speculation. And unfortunately, when the untested hypothesis is repeated enough, it becomes historical fact that is hard to dispel. But that’s just my two cents worth…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Deer Hunts, Wilderness Classroom

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on A Structure for Learning

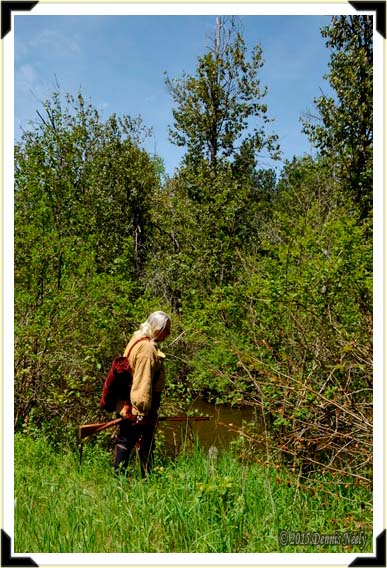

“Behind, Not in Front”

“Snapshot Saturday”

Like the creatures of the forest, an 18th-century woodsman should utilize the cover to his or her greatest advantage. Certainly, sitting behind the oak in the midst of a hemlock bush is not as comfortable as leaning back against the tree’s trunk, but the difference from a deer’s perspective is striking. A trading post hunter, two ridges east of the River Raisin in the Old Northwest Territory, in the Year of our Lord, 1798.

Posted in Skills, Snapshot Saturday, Wilderness Classroom

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “Behind, Not in Front”

Balancing One’s Historical Perspective

Ears twitched. Deer flies hovered over a hat-sized patch of mud, dried on a muscled shoulder. A long, black, broom-like tail swished twice, almost reaching the closest steer’s back, the largest one, an Angus/Limousin cross. Three cinnamon-red Herford/Limousin-cross cattle stood just beyond the ringleader. One of the “reds” raised then thrust down a cloven hoof. A small dust cloud marked the spot.

Three Sandhill cranes chortled to the southwest, around the bend in the wagon trail and up on the first hill in the tilled field. A dozen minutes before, that trio stood erect with their slender beaks following the plodding progress as three gray-haired backcountry boys urged the four head along. The prairie grass beside the bean field smelled of dew, burning off in the brilliant sunlight of a humid July morn.

Three Sandhill cranes chortled to the southwest, around the bend in the wagon trail and up on the first hill in the tilled field. A dozen minutes before, that trio stood erect with their slender beaks following the plodding progress as three gray-haired backcountry boys urged the four head along. The prairie grass beside the bean field smelled of dew, burning off in the brilliant sunlight of a humid July morn.

The lower field’s headlands, where the four now rested, showed nary a wisp of greening sprouts, thanks to a late spring drought. There the air was parched, dry and dusty. The only hope of a potential crop was rocks and gravel. Why the cattle decided to stop there defied reason, but cows don’t reason well, do they?

Walt, the farmer who owned the wayward steers, shook a bucket half-filled with shelled corn. The southern-most steer turned and looked at him. It raised its head and appeared ready to start walking again, but the Angus, the one we started calling “That Black Devil,” wouldn’t budge. He faced south, content to just stand and switch his tail and chew and drool.

Not knowing these four, fifteen paces was as close as I dared venture. We all spoke soft, urging then to again strike off on the journey home, but they were not ready to move, at least the Black Devil wasn’t. Patience is a virtue when herding cattle. A steady plodding beats a fast walk, or worse yet, an outright run.

Then, for no apparent reason, the Angus turned and started walking to Walt. The others followed. Jerry, another neighbor, said, “They must have rested enough.” There’s just no reasoning with cattle…

Longhunters and Farming

I joked for several days about joining Gil Favor’s cattle drive. “Head ‘em up, and move ‘em out,” “watch those dogies,” and “where’s Wishbone, I need some grub” intermixed in my everyday conversations. Strange looks, what strange looks? One or two of the references wandered into texts or emails. By the weekend my family thought I needed a serious intervention, but I doubt they have ever seen the early 1960s television western, “Rawhide.”

As kids, the whole family sat in front of the Spartan television that Dick Knapp sold to my parents and watched “Rawhide,” “Wagon Train” and “The Rifleman.” The screen was an icky- green and showed a black and white picture that moved—impressive stuff. The case was solid mahogany filled with neat vacuum tubes that lit up—you could see them through the little vent holes in the back. Hey, there’s a reason I’m easily distracted…

Anyway, as I walked behind the steers, I found myself humming the theme song to that show. I used to do that when I was a kid and helped wrangle the dairy cows. I suppose that is a version of time traveling. I looked up the show and discovered it ran from 1959 to 1965. The scary part is when you stop to do the math and realize that was a half-century ago. Some days living history/time travel has a more frightening side to it.

When we had our little “standoff” in the bean field, I felt myself slipping farther back than just a half century. Before those few minutes, I tried real hard to picture the four head of cattle in an 18th-century setting. Not being dressed in period-correct clothes and not having “Old Turkey Feathers,” my Northwest trade gun, in my hand didn’t help the situation any. I should have known better. A traditional black powder hunter can’t force his or her way back into yesteryear’s cobwebs.

I stared into the eyes of the Angus. He stared back and drooled a bit. In hindsight, at that moment I felt myself drifting, physically moving, or so it seemed. Perhaps it was the heat, but I couldn’t perceive either Jerry or Walt, only those steers before me. I glanced to the south, then to the north. I turned to my right and checked my back trail. “This is how Jonathan Alder became a captive,” I whispered.

“It was now the month of May 1781 [an editor’s note: (March 1782; Howe, Beers) refers to other versions of Alder’s narrative] when the leaves were all out and the woods were very thick. One pleasant and sunshiny morning, everything looked gay and beautiful and my mother called to my brother David and myself and told us that we must go and hunt a mare and colt that had been missing for several days…” (Alder, 29-30)

The brothers found the mare and colt, but the colt would not get up. Alder continued:

“It had eaten the plant called ‘stagger wood.’” As the brothers worked to get the colt up, David “…hallooed out, ‘Run, there is Indians!’…there were five Indians in all, and one white who had been taken prisoner years before…I could not move, and by the time I looked around (for they came up behind me), one Indian was right up to me and held out his hand and took hold of it…” (Ibid, 30)

The mystique of those few fleeting pristine moments evaporated when the steers left the wagon trail and turned north on the gravel road that led back to the Wright homestead and barnyard. But as so often happens, my mind mulled over those pristine moments, especially my looking about, in the context of the 1790ish frontier.

As living historians and traditional hunters, we spend countless hours sifting through primary documentation in search a tiny golden nugget, yet we often fail to recognize the gold dust that exists in our own life experiences.

As I thought about Jonathan Alder chasing the mare and colt, I realized I have a modest amount of background tending farm animals, and further, farming in general. That knowledge never makes its way into my traditional hunting/living history scenarios, and it should.

About four years ago I purchased and read Joseph Ruckman’s book, Recreating the American Longhunter: 1740 – 1790. I picked the book up again and started re-reading it a week before Walt’s steers got out. One passage in particular stuck in my mind and came to the fore while I jogged to get ahead of the steers as they decided to make one last break for freedom. Two read arrows mark that passage; the one sentence is highlighted in yellow and underlined in red:

“…I want to dispel the myth that the longhunters spent all their time hunting or among the Indians. Those whom we remember best as longhunters—i.e., Daniel Boone, Simon Kenton, the Cresaps, and the Gists—were primarily farmers, and to a slightly lesser extent, cattlemen and herdsmen. Hunting and exploring were essentially sidelines, and dealings with Indians were more often than not of a hostile nature. The point is, if you want to portray a believable longhunter, you should know something about farming…” (Ruckman, 7)

As a living historian, I feel I sometimes put too much emphasis on one or two paragraphs devoted to a woodman’s hunting exploit. That may be just me being too hard on myself, but by narrowing my focus, I lose sight of the overall picture, sometimes to the detriment of the authenticity of the impression. There are other instances of farming and animal husbandry woven within the fabric of many a hunter’s tale, but I’ll let those be, for now…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Persona, Worth thinking about...

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on Balancing One’s Historical Perspective

“Beneath an Autumn Olive”

“Snapshot Saturday”

Posted in Snapshot Saturday, Wilderness Classroom

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “Beneath an Autumn Olive”

Ornery Beyond Common Civility…

The last month or so has been really busy, beyond belief, really. Between the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association’s Spring National Shoot, covering several Michigan black powder shooting events, including the Old Northwest Primitive Rendezvous, and trying to deal with the utility company’s tree trimming crew, the last few weeks have not been my own.

The greatest disappointment is the loss of over 200 trees on the North-Forty, the majority of which did not and would not pose any threat to the power lines and/or public safety in the foreseeable future. But “…we have to adhere to the standards we set…,” which really means “You don’t own your own property…”

And there is little concern about disrupting one’s writing business or saddling the land’s steward with the cost of cleanup once the last trim-truck pulls out. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to turn the happenings of the last two weeks into a positive 1790-era happenstance. Maybe in a few months or so?

On a more upbeat note, I “signed on” as a trail hand for a cattle drive Thursday morning. At most, my term of employment was only a couple of hours. Years ago, when the dairy cows got out, I used to hum the theme song to the old western “Rawhide” (well it wasn’t “old” back then) as we herded them back to the field.

As the neighbor’s steers turned the bend in the two-track, I caught myself humming that tune. I expected Rowdy Yates to come riding up in a cloud of dust with Wishbone’s chuck wagon clattering and flapping close behind. And although I was “not dressed for the occasion,” I did experience a few pristine moments that dovetailed with one of the points in Joseph Ruckman’s book, Recreating the American Longhunter: 1740-1790. More on that in the near future…

So yes, I’m still alive and kicking, and to hear the utility company employees tell it, ornery beyond common civility…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in General

Tagged Black powder hunting, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

2 Comments

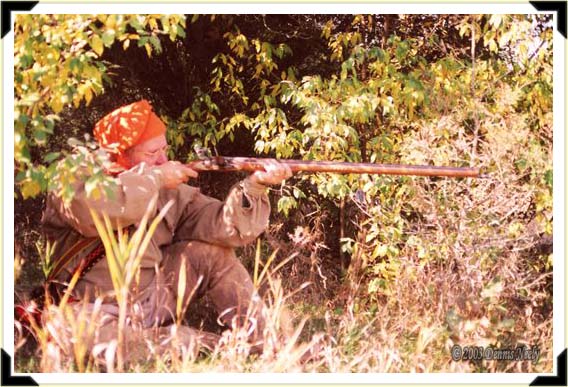

“Absorbed in Another Time”

“Snapshot Saturday”

Lost in his 18th-century Eden, a post hunter sits concealed within the forest’s natural cover. Twenty-first-century observers are always concerned about a traditional black powder hunter’s lack of reliance on state of the art camouflage clothing. Images such as this one help dispel that misconception. Old Northwest Territory, one ridge east of the River Raisin, 1798.

Posted in Snapshot Saturday, Wilderness Classroom

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “Absorbed in Another Time”