“Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!”

The wild turkey’s melodic tone hung in a quiet, frosty calm. That tom was still roosted, on the hog-back ridge, over the hill and across the big swamp. Night’s abyss abated with reluctance that fine morn in 1798, or so it seemed.

“Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark.”

The hen sounded scratchy, juvenile. She too was roosted, but sixty paces to my left in the cedar grove. A wild turkey had not spent the night in that area in a long time, not since the passing of “Spins like a top,” a long-bearded gobbler that could not slow dance.

“Ark, ark, ark, ark.”

An older, raspy-voiced matron barked back at the youngster. That hen was still secure in the confines of the big spreading oak that overlooked the east side of the big swamp, maybe ninety paces straight ahead.

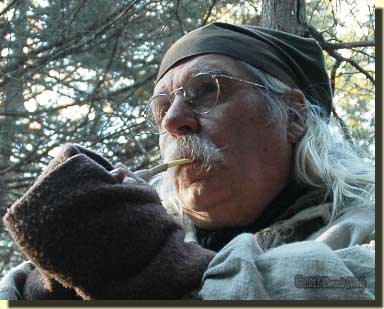

Anxious, cold fingers rummaged through the shot pouch’s meager contents in search of a single wing bone, worn smooth from handling and polished by the buckskin bag’s plain interior. The bone clicked against the Northwest gun’s flint lock when fetched, drawing a scowl, then found its way into the woven sash about my waist. The moment was not yet right.

In due time the thrash of big wings told of wild turkeys flying down from the roost, across the meadow, near the great spreading oak. “Three…four…five…,” my mind counted. I never heard the hen in the cedar grove fly down, but as expected, the older hen sounded the morning assembly: “Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark.”

“Gob-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl!”

The tom chimed in about then. He was on the ground, part way down the east face of the hog-back. The wing bone call found my tongue-wet lips. With steady draws of cool morning air, I imitated the old hen: “Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark.”

The tom chimed in about then. He was on the ground, part way down the east face of the hog-back. The wing bone call found my tongue-wet lips. With steady draws of cool morning air, I imitated the old hen: “Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark.”

Twenty long, silent minutes ticked away. Wings flailed in the cedar grove, followed by a single, soft, reserved-sounding “Putt.” A few minutes later a shiny black hulk circled a sizeable autumn olive that grew at the meadow’s edge. A cautious gray head bobbed up and down, appearing and disappearing as it herky-jerked closer.

The timid hen stepped into a sunlight spear, took three bold steps into the frost-encrusted prairie grass and stood upright. “Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark.”

Still erect and alert, the turkey’s gray pate turned and halted, back and forth, as the bird’s keen brown eye slashed away at the brushy cover along the meadow’s southeast boundary. The hen took two steps into the meadow, then changed her mind, spun about, walked off to the northwest and melted behind the rolling knoll.

Not long after, a distinctive red and blue head circled the same autumn olive, but the gobbler rounded the bush in the opposite direction. This tom was twice the size of the hen that preceded it, but in the end, the long-beard stopped not a trade-gun’s length from where the hen yelped. The gobbler fanned his tail and fluffed his feathers, then pirouetted once to the right, once to the left.

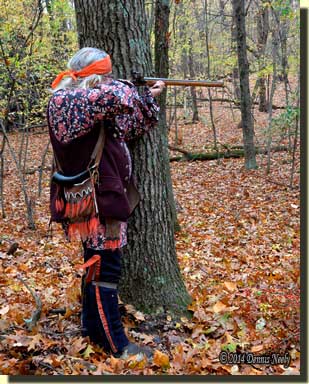

That gobbler waited a fair amount, then turned about and headed northwest. When his head passed behind the knoll, I put the wing bone to my lips and clucked once, soft and seductive. I expected he might cross over the knoll or at the least, stand on the crest. The Northwest gun was up and ready for either possibility. The hunter’s prayer crossed my lips when he first appeared.

A dozen minutes later, the tom walked back to where the hen called. He fanned and moved a bit to the east, then folded his tail. He fluffed his feathers and flapped his wings as if in preparation to gobble, but he did not. Thirty-five yards was just too far for the death bees, and it seemed that wary gobbler knew that.

Traditional Black Powder Hunting 101

The essence of the online post was that the individual killed a spring turkey with a modern shotgun and that he was going to purchase a second license and try for a gobbler with his French fusil de chasse. His question was, “Do I still wear camo, or can/should I dress in my re-enacting clothes?”

As is normal, forum followers responded with a variety of opinions, some not on-topic, but that will never change. A few people expressed envy that the thread’s author lived in a state that allowed multiple kill tags for spring turkey hunters—Michigan does not.

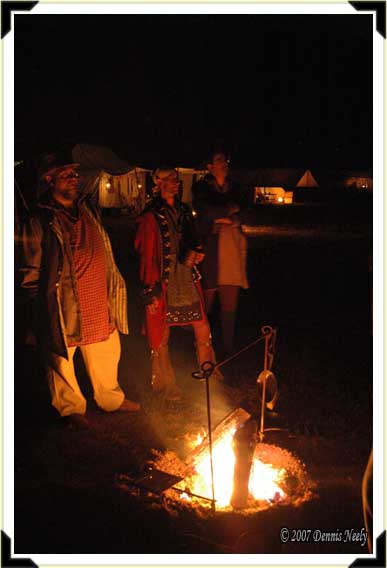

But within the thread was an underlying feeling that traditional black powder hunting was an all or nothing sport, and that is not the case. That misconception came to light a number of times at the Outdoor Life/Field and Stream Michigan Deer & Turkey Expo last month.

The conversations were all similar. An individual wants to see what traditional black powder hunting is all about, but they don’t want to hunt in a traditional style all of the time. In response, my line of questioning is usually the same: “Do you bow hunt? Do you gun hunt? Do you hunt small game? Do you hunt deer? Do you hunt turkeys? Do you hunt waterfowl? Do you hunt with a muzzleloader?”

The minute I get two or three “Yes” answers, I point out that most avid hunters pursue a variety of hunting styles, using different arms and/or archery tackle. The choice of game, arm, bow, gear, etc. for a given outing is up to that person. Within modern hunting methodology there seems to be no problem switching from one discipline to another.

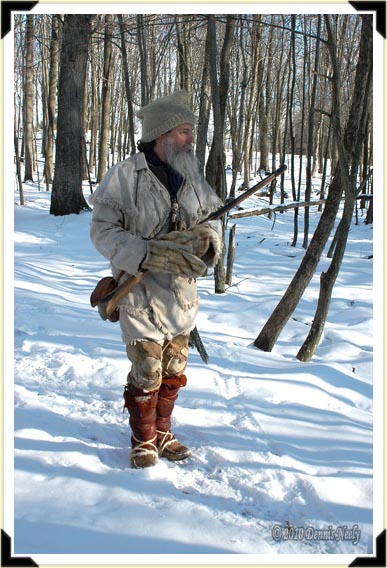

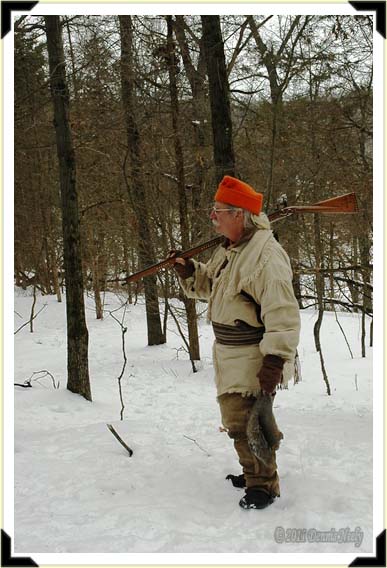

Traditional black powder hunting should be no different, but that is not the perception of the hunting public. A huge wall seems to appear when the conversation turns to considering an excursion to yesteryear. Somehow a disconnect exists between buying a state-of-the-art bow, space-age arrows, ultimate tree stands, science-proven scent-blocking camo suits and the like and owning a smooth-bored flintlock, wool leggins, a trade shirt, a sleeveless waist coat and the rest of the trappings associated with an 18th-century woodsman.

Traditional black powder hunting should be no different, but that is not the perception of the hunting public. A huge wall seems to appear when the conversation turns to considering an excursion to yesteryear. Somehow a disconnect exists between buying a state-of-the-art bow, space-age arrows, ultimate tree stands, science-proven scent-blocking camo suits and the like and owning a smooth-bored flintlock, wool leggins, a trade shirt, a sleeveless waist coat and the rest of the trappings associated with an 18th-century woodsman.

Dollar for dollar, I would bet the investment is greater for the modern hunter than the traditional enthusiast, but the difference is in the type of hunting gear required for a history-based pursuit—the arms, the accoutrements, the clothing is “different.”

And further, traditional black powder hunting, by its very nature, represents old, worn-out technology that was discarded literally centuries ago, or so I’m told. To hear some of these folks ramble on, sometimes I think we might as well be advocating hunting in a clown suit…

I can understand the impressions of modern hunters, but seeing living historians, re-enactors and members of the black powder shooting sports communities react with the same disbelief is hard to swallow. It was clear to me the gentleman that made the initial post considered his fusil de chasse an inferior, second-choice arm—even with a turkey in the pot and essentially nothing to lose, he had reservations. Perhaps I was wrong for not adding my two-cents to the discussion, but with where the comments were going, I felt there was no point in inciting the wrath of the forum trolls, as they are sometimes called.

The point I try to make with anyone new to traditional black powder hunting is to move at your own pace. Start with a basic gun, a trade shirt and a blanket. Devote every Tuesday to dabbling with a traditional hunt, in and out of season. Do you not devote off-season time to improving modern hunting skills?

Maybe start with a history-based squirrel or rabbit hunt, a simple pursuit that will not risk “missing the chance of a lifetime.” But be aware, if you miss with your modern, semi-automatic suppository gun, you still “missed the chance of a lifetime.” The points of the discussions are all a matter of perspective…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Every so often someone asks how I bind my bedroll with the leather portage collar. “Roll the blanket and tie it,” seems like the logical answer. But over the years I have experienced many failures of tying methods that I thought were suitable and simple enough. The worst disasters have occurred in the heat of the chase—I mention two noteworthy instances and allow the reader to imagine the details.

Every so often someone asks how I bind my bedroll with the leather portage collar. “Roll the blanket and tie it,” seems like the logical answer. But over the years I have experienced many failures of tying methods that I thought were suitable and simple enough. The worst disasters have occurred in the heat of the chase—I mention two noteworthy instances and allow the reader to imagine the details.