-

Recent Posts

Categories

Archives

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

Blogroll

Forums

General Living History

Historical Sites

Organizations

Artists

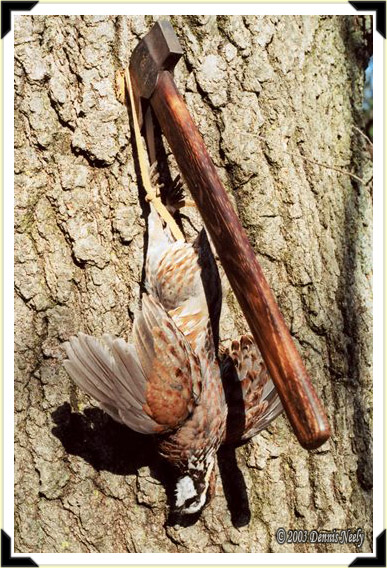

“Bobwhite at the Section Oak”

Posted in Quail Hunts, Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “Bobwhite at the Section Oak”

A Pleasant Interlude

Sunlight sparkled on fresh frost. A puff of frozen breath foretold of the older doe’s arrival. Ears twitched, then dropped from sight. Her head popped up, but her gaze was off to the north. She flipped her ears back before she turned and stared at her back trail. In time the sleek doe’s back came into view. Ten or so steps closer, she paused and nuzzled the leaves beside the lower trail.

“Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark, ark, ark…” A wild turkey hen made her presence known on the far side of the big swamp. “Ark, ark,” came an answer, down the hill and around the bend from the raspy old hen. A blue jay flew by the humble ambuscade, then swooped up into the forked oak at the swamp’s edge, the one by the middle crossing, just south of the little poplar grove.

Two younger deer walked into sight, the second puffing more than the first. One foraged to the right of the trail, the other to the left. Their mother glanced back, then plodded ahead. The trail snaked to the east of a downed tree top. The parent oak was huge with wide-spreading limbs, the trunk stout and hollow. A heavy gust in the midst of a downpour broke away both of the east-facing branches. Clusters of dead, brown leaves still clung to the twigs. The foliage swallowed up the matriarch’s meandering silhouette.

Two younger deer walked into sight, the second puffing more than the first. One foraged to the right of the trail, the other to the left. Their mother glanced back, then plodded ahead. The trail snaked to the east of a downed tree top. The parent oak was huge with wide-spreading limbs, the trunk stout and hollow. A heavy gust in the midst of a downpour broke away both of the east-facing branches. Clusters of dead, brown leaves still clung to the twigs. The foliage swallowed up the matriarch’s meandering silhouette.

The yearlings browsed behind the oak’s fortification. A white tail flashed in a space where two rum-keg-sized branches forked. The older doe reappeared with a hearty puff, what seemed to be the deer equivalent of a gentle sigh. Leaves crunched in cadence with her hoof-falls.

Straight downhill, maybe twenty-five paces distant, this forest tenant stopped near the base of a modest red oak. She gazed about and twitched her ears. I breathed down, forcing my warm breath over my chin and into the wool trade blanket that hugged neck. I squinted to avoid eye contact.

The doe pawed with hard strokes of her left front hoof. Leaves flew and fluttered, piling up beneath her midsection. Her shiny black nose smelled the upturned earth. She pawed once more, then she nibbled at an acorn, then another, then another.

The two young deer caught up with her. The one that trailed behind sported velvet nubbins. He pushed the young doe into her mother’s hip. The mother turned her head, opened her mouth and pulled her nostrils back, looking as if she was about to bite the rambunctious offender. The button buck pushed again, and mother knew better, choosing instead to utter a low guttural bleat.

The three milled about under that oak tree for a fair amount of time, pawing leaves and crunching acorns. Heads popped up, noses sniffed and ears flipped in all directions. Several blue jays perched overhead, jockeying silent from tree limb to tree limb. Yet, never once did any of these wilderness creatures detect a trading post hunter lurking uphill in a different tree top—a gentle, southeasterly breeze held the smell of death at bay.

On that crisp November morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1794, a Northwest gun, charged with an anxious death sphere, rested across the woodsman’s hunt-stained buckskin leggins. A fine stag was his only concern. The doe and two yearlings were but a pleasant interlude…

“…the first time I ever saw a deer”

The primary purpose of any traditional black powder hunt is to put food on the family dining table, but the woodsman’s goal is to do so in a manner that adheres to the methods used by our forefathers.

Joseph Doddridge devoted a small chapter in his hallowed recollections to hunting. He begins by stating that the woods supplied a fair amount of the settler’s subsistence. He tells of deer, bear and fur skinned animals, and he describes the hunting camp and names it “a half-faced cabin.” (Doddridge, 99)

When Doddridge speaks about the hunting camp and the conversations around the evening fire, he talks of “the spike buck, the two and three pronged buck, the doe and the barren doe…,” leaving the impression all deer were the object of the hunt. In short, his fellow backcountry inhabitants were, as he said, subsistence or meat hunters. (Ibid, 101)

When Doddridge speaks about the hunting camp and the conversations around the evening fire, he talks of “the spike buck, the two and three pronged buck, the doe and the barren doe…,” leaving the impression all deer were the object of the hunt. In short, his fellow backcountry inhabitants were, as he said, subsistence or meat hunters. (Ibid, 101)

Little is written about Josiah Hunt, one of my favorite hunter heroes. But thanks to a biographical letter by T. C. Wright, we know that Hunt was a hunter of exceptional skill. He provided meat for General Anthony Wayne’s Legion of the United States’ winter camp at Greeneville, Ohio in 1793. (Howe, 199)

On that morning, as the old doe and her two offspring munched acorns not twenty paces distant, I felt like Josiah Hunt was sitting next to me, watching to see if I would take the shot and put meat on the table. The shot pouch held an antlerless and a buck tag, both unfilled, and from the admonitions that floated through my subconscious, I’m sure Josiah knew that, too. But my family had use for one deer, which is part of the reason I passed on the does. Under my breath, I shushed Josiah’s impatient urgings.

Fortunately, from an historical perspective, Joseph Doddridge made provision for my desire to wait for one specific buck:

“Often some old buck, by the means of his superior sagacity and watchfulness, saved his little gang from the hunter’s skill by giving timely notice of his approach. The cunning of the hunter and that of the old buck were staked against each other, and it frequently happened that at the conclusion of the hunting season the old fellow was left free, uninjured tenant of his forest…” (Doddridge, 101)

Recently, research for my trading-post hunter persona found me skimming through George Nelson’s journal. Nelson was fifteen-years-old when he signed on as a clerk with the XY Company. He departed LaChine, bound for the Grand Portage on the western end of Lake Superior, on May 3rd, 1802. Barely underway, Nelson wrote:

“…At ‘Portage des Chenes’ [Oak Portage], now ‘Aylmer,’ the people [voyageurs in his canoe] saw a Red Deer swimming over the West Side, they pursued, overtook & killed it. This was the first time I ever saw a deer.” (Nelson, 37)

I have that passage marked, and when I read it, my mind immediately dashed back to the morning when I watched those three deer scrounge for acorns. I don’t know why, but that’s what I thought of.

At first, I felt a twinge of guilt. As an 18th-century time traveler, I’ve been in countless situations like that morning. I had no intention of unleashing the death sphere at any of those deer. Instead, I relished the opportunity to observe unhindered wild white-tailed deer go about securing their subsistence for that day.

Even though such encounters number in the thousands, I never take the daily comings and goings of God’s creatures for granted. I don’t remember the first time I saw a white-tailed deer, but I have been a part of showing others such wonders, especially the grandchildren.

As living historians, we all tend to put our hunter heroes on pedestals. We hang on their every word, and the good ones we quote back as justification for what we do, what we wear or what we carry. The historical me that emulates the trading post hunter relies on a number of George Nelson’s musings and/or descriptions for such justification. Yet, to a certain degree, I have failed to put or keep his life in a proper perspective.

Nelson was a fifteen-year-old boy who, for five pounds a year for five years’ service, agreed to travel into the wilderness and learn the fur trade. One of his first stated concerns was how “deeply loaded” the bark canoe was and how “the least movement made them swing…often I thought we should upset…” (Ibid, 34)

And then, amidst all of these new sights and sounds and tastes and smells and feelings, Nelson’s voyageurs spot a red deer swimming in the water. “This was the first time I ever saw a deer,” the youthful Nelson writes. What a revelation…

Read a little closer, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Deer Hunts, Living History, Worth thinking about...

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on A Pleasant Interlude

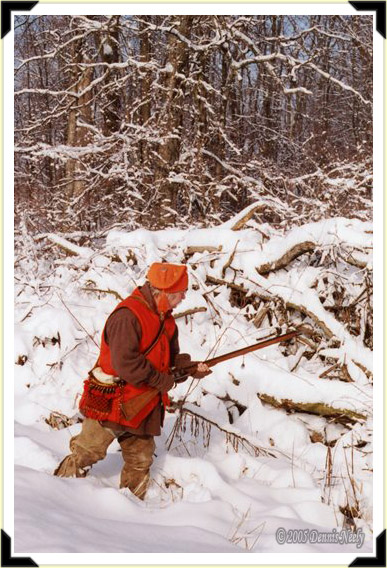

“A Cottontail Morning’

“Snapshot Saturday”

Posted in Rabbit Hunts, Snapshot Saturday

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “A Cottontail Morning’

Sharing the next step…

A distant crow cawed. Msko-waagosh shuffled sideways. A fox squirrel chattered. A crimson cardinal exclaimed, “Whit, whit, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu…” A shiny, silver needle pierced the weathered canvas. The needle’s length grew short. The eye slipped through the weave. The thin cord followed with a tug from a thumb and forefinger.

“Aww, aww, aww, aww…” Three crows cawed above the cattails on the west bank of the River Raisin, or there abouts. The screams grew louder as the birds drew closer. The needle’s blunt point emerged from the fabric, above the horizontal cherry-sapling lashed to one of the wigwam’s hoop bents. The point dove back into the canvas, a few threads to the south of the first pass and under that horizontal rib. “Aww, aww, aww, aww…” A dozen screaming black demons swirled over the bottom slash, just over the hill, at the edge of the hardwoods.

Riled-up crows flew from all directions. “Aww, aww, aww, aww…” When the needle emerged, Msko-waagosh’s fingers pulled the cord through the eye, then he put the needle between his lips, so as not to lose it. “Aww, aww, aww, aww…” An owl flapped quick, flying low through the oaks, maples and hickories. The woodsman’s fingers pulled the cord tight, then started a slipknot. The gray streak swooped up, slowed, then disappeared in the thick green leaves of a young maple. “Aww, aww, aww, aww, aww, aww, aww, aww…”

An uncountable mass of black–winged assassins boiled in and out among the treetops, swarming with the fierceness of offended white-faced hornets. “AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW…” The forest offered no sound but the would-be combatants’ shrill hollering.

Elk moccasins shifted sideways. Brown, dry leaves rustled, but made no audible sound. “AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW…”

The shiny, silver needle again pierced the canvas, then passed from sight. The crows hushed, or so it seemed, despite the continued antagonism of a half dozen persistent birds. Crows lit in the treetops, then sat and waited. Some murmured amongst themselves, like young children shushed in church. The needle’s second loop complete, the cord pulled from the eye and the needle safe in his lips, Msko-waagosh tied another slipknot.

“Aww, aww, aww, aww…” On the southernmost edge of the flock, a lone crow cawed, took flight, then winged southeast. Others followed, some “awwing,” some not. Again the dusty moccasins stepped to the right, and the needle went about its task. Crows followed crows, and in the course of two minutes the screaming demons were but an exciting 1790s-era memory…

“…they built a wigwam…an Indian camp…”

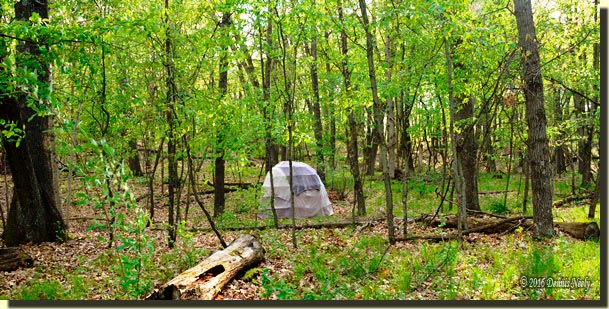

The wigwam project has generated a fair amount of interest; unfortunately, I do not have sufficient knowledge or experience to answer all of the inquiries that fly through cyberspace. This endeavor is another laboratory assignment in the wilderness classroom, an ever-evolving lesson in progress, shared as it happens. Simply put, Msko-waagosh’s wigwam is another opportunity to explore a sense of kinship with long-dead, 18th-century hunter heroes.

The wigwam project has generated a fair amount of interest; unfortunately, I do not have sufficient knowledge or experience to answer all of the inquiries that fly through cyberspace. This endeavor is another laboratory assignment in the wilderness classroom, an ever-evolving lesson in progress, shared as it happens. Simply put, Msko-waagosh’s wigwam is another opportunity to explore a sense of kinship with long-dead, 18th-century hunter heroes.

By its very nature, a living historian’s hands-on education depends on trial and error experimentation, the results of which are measured, or perhaps interpreted, as successes and failures attained in the midst of a simulated slice of long ago. A part of this learning process is attempting to comprehend the sometimes feeble explanations penned on the yellowed pages of a grizzled old woodsman’s surviving journal. Another part is the faithful re-creation of what the student thinks those words mean, or were intended to convey.

Still another aspect is the constructive reflection after completion of the lesson plan, and of course, the formulation of future experiments designed to explore the myriad of unexpected questions that arise from what one thinks is a simple exercise in gleaning historical understanding. And in the end, the true test of any meaningful wilderness classroom lesson is the careful duplication of the experiment by others, undertaken in like circumstances, following the same process and producing like results.

In the early stages of his captivity, Jonathan Alder wrote:

“We crossed the Ohio about the middle of the afternoon and that evening one of the Indians went out and killed a deer. We went up to higher ground and selected a spot conveniently near to water and wood. It was always the Indians’ custom to burn dry wood (something that was generally easy to find) and also to camp near water. Next they built a wigwam, or what was called an Indian camp, and peeled bark and covered it and made it tolerably comfortable to what we had been accustomed to before…” (Alder, 38)

Unfortunately, Alder’s use of the word “next” is unclear. Did he mean that evening or the next day? Reading further, Alder states that two or three days hence his captors killed a large buffalo and set about making dried buffalo, or “jerk” as he called it, and that they stayed at this camp/shelter for “about two weeks.” He also notes, “we moved on, leaving our wigwam, never to see it again…” (Ibid, 39)

James Smith spoke of the Ottawa making “tents” using “flags,” cattail or rush mats, which he described as “…plaited and stitched together in a very artful manner…each mat is made fifteen feet long, and about five feet broad…” (Smith, 67)

He tells of one style of tent that sounds like a teepee, but in a later passage he also describes a shelter that resembles a “sugar loaf,” or the general wigwam shape:

“At night we lodged in our flag tents, which when erected, were nearly in the shape of a sugar loaf, and about fifteen feet in diameter at the ground…” (Ibid, 72)

Again, Smith is a little more specific in that the wigwam was constructed at the end of that day’s journey, utilizing existing covering material in the form of the flag, or cattail mats. Later, Smith reinforces the impression that these shelters were put up in a short span of time, and expands on the construction method used for a “sweat-house:”

“When we encamped, Tecaughretanego made himself a sweat-house; which he did by sticking a number of hoops in the ground, each hoop forming a semicircle—this he covered all round with blankets and skins…” (Ibid, 110)

Both Alder and John Tanner speak of using “tents,” and the context implies, but does not specifically state, a canvas tent/shelter. Tanner refers to many shelters as “lodges,” and tells of using a piece of painted cloth for a shelter. Early on in his narrative, Tanner describes using buffalo hides for what appears to be a temporary shelter used on a long journey, but he does not describe the structure’s physical make up—a wigwam, perhaps?

“We had thrown away our mats of Puk-kwi [woven cattails], the journey being too long to admit of carrying them. In bad weather we used to make a little lodge, and cover it with three or four fresh buffalo hides, and these being soon frozen, made a strong shelter from wind and snow. In calm weather, we commonly encamped with no other covering than our blankets…” (Tanner, 36)

These written passages led me to construct a smaller wigwam, about nine feet in diameter instead of fifteen as Smith’s night lodging was, suitable for one or two hunters on a temporary basis. Now “temporary” for me means for an extended period of time, because I cannot move my hunting camp three or ten or forty miles down the River Raisin due to modern property rights issues. My 1796 adventures must take place within the boundaries of the North-Forty.

Likewise, skinning live trees for bark covering or spending hours weaving cattail mats is just not feasible, plus the cattails or rushes are not “in season” at this time, either. By default, canvas is the best alternative for the project, although such a covering material is more in keeping with a 19th-century wigwam.

And even then, I opted for cutting apart the seams of inexpensive, eight-ounce painter tarps instead of investing in high-quality canvas. The washed and dyed tarps will provide ample learning opportunities with an eye toward the future use of cattail mats and/or bark. After all, Msko-waagosh’s wigwam is but one more moccasin step down the unending path to yesteryear—and I look forward to sharing the next step…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Hunting Camps, Living History

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on Sharing the next step…

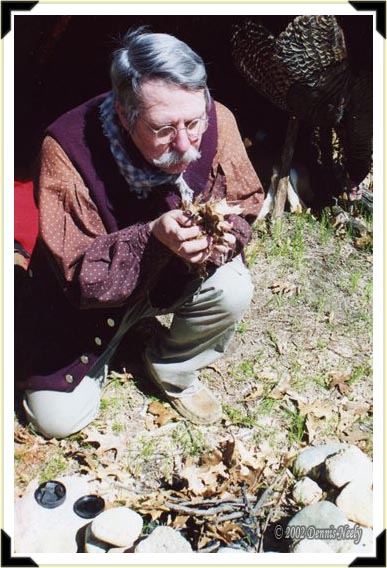

“Kindling a Morning Fire”

“Snapshot Saturday”

Posted in Hunting Camps, Snapshot Saturday, Turkey Hunts

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “Kindling a Morning Fire”

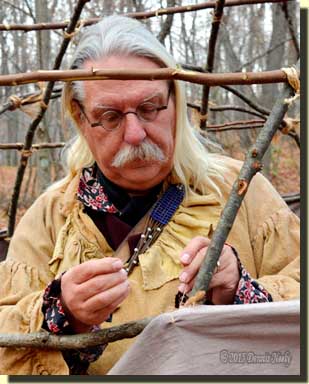

Finally Hanging Canvas

The Northwest gun leaned against a small red oak, its girth the same as a brass kettle that trades for five beaver pelts. The open-topped, Ottawa-style shot pouch hung from the muzzle, as did the bison powder horn. Two steps away a finger-long needle slipped through a grayed canvas piece. The fiber cord bound the canvas’ upper edge tight to the bent cherry sapling.

I could hear Ziibi Ikwe, River Woman, my Ojibwe mother, admonishing me for the wigwam’s pitiful shape. Thankfully, she would never see this shelter. The east side saplings bent as they should, the west ones were of a poorer quality with many knots. Their arch was flatter, rather than round.

I could hear Ziibi Ikwe, River Woman, my Ojibwe mother, admonishing me for the wigwam’s pitiful shape. Thankfully, she would never see this shelter. The east side saplings bent as they should, the west ones were of a poorer quality with many knots. Their arch was flatter, rather than round.

A chipmunk’s steady chirping echoed throughout the woodlot. The striped rodent sat on a rotted log on a little rise, displaying all the nobility of a captain at the helm of a great ship adrift on a sea of damp leaves. A blue jay’s contented song, “Swip-it! Swip-it!” punctuated the chipmunk’s melody. With some looking, my eyes found the bird perched on the jagged remnants of a broken limb, high up in an oak to the west.

A stout tug pulled the needle through the canvas weave. The cord’s fibers slipped through the eye. The silver needle rolled, then tumbled free, end-over-end into a clump of ankle-deep green grass that grew through two fall’s worth of oak leaves. My eyes marked the spot as if it was the last glimpse of a wounded buck’s flight.

I knelt expecting to pick up the needle, but it was nowhere in sight. My fingers removed leaf after leaf, placing them to the right beside a small grove of two-leafed maple spouts. Twice I looked up and scanned the forest, then the needle fell from between two large brown leaves.

Another chipmunk chirped, off to the west. It ran through a small patch of trilliums and into a hollow log. In a few moments, it popped out of a limb that pointed upward. Then all sounds ceased. The glade grew chilly and spooky quiet. Overhead, the unfolding leaves did not seem to touch each other, yet they rustled as if driven by a steady wind. Without conscious guidance, my elk moccasins stepped to within an arm’s reach of the Northwest gun, pouch and horn. I stood still, watching, waiting.

Off toward the River Raisin’s sand flats, a single goose honked over-and-over—just a single “ke-,” not the full “ke-honk” or “ke-honk, honk.” A bit relieved, I grasped the next canvas piece and held it up to the horizontal rib that was chest high. I folded the canvas edge over the finger-sized sapling, pushed the needle through the weave, looped it twice and tied it off, binding the panel’s corner to the wigwam’s frame. About then a bullfrog started croaking over the rise and down the hill in the stagnant pool in the nasty thicket near the isthmus. I smiled. I was finally hanging canvas…

A Return to the Wilderness Classroom

The past few weeks have been especially strenuous and exhausting. There is no relief in sight. The days grind on and the “must do list” never seems to get shorter. In a fit of frustration, I pushed away from the desk. For my own sanity I had to take a break from the phone calls, emails and appointments. Scribbling time has been almost non-existent, though somehow I have met all of my deadlines. As I bolted out the door, I told myself to hold all calls and all appointments until 11 o’clock. An office staff of one still needs reminders and occasional guidance, at least the historical me thinks I do.

The wigwam’s frame went up in October, my third in thirty-plus years. Msko-waagosh harbored fond thoughts of using that shelter throughout the fall hunts, but that plan never came to fruition. For whatever reason, fruitful lessons in the wilderness classroom sometimes require a long recess.

I managed to hang two pieces of canvas, each 4-foot wide by 12-foot long, but they did not suit my liking. They looked far from period-correct. I secured the top edge first, but the wigwam’s dome shape requires more material at the bottom, and I forgot to take that into account. I got snowed out, so those two pieces of canvas remained on the frame throughout much of the winter.

When the spring classroom bell rang, I began the lesson by cutting each piece of canvas in half, yielding 6-foot sections. The shorter length minimized the distortion issue. Stress melted away with each stitch. My attention focused on securing one piece of the wigwam’s covering at a time, intermixed with surveying the forest for impending danger.

I established a rhythm after the second piece. I imagined an Ojibwe family could cover a wigwam’s frame in a fraction of the time it took me. Like all wilderness classroom learning, hands-on experience and careful replication smooths any 18th-century process. By my twenty-fifth wigwam, my handiwork should meet my adoptive mother’s expectations.

Just being in the woods was a relaxing treat. On the way out I thought about turkey hunting first, but deep down I knew there wasn’t sufficient time to do justice to both. The wigwam, or lack thereof, has gnawed at my innards all winter long. For me, there is a huge difference between learning from a failed attempt, and failing to attempt. Finding time has been a critical factor in the last few months, but still…

Seeing steady progress told me that I made the right choice. I never heard nor saw a wild turkey. Working with my hands took my mind off 21st-century distractions, but to a greater degree, I feel the joy of that morning rested in the little creatures of the glade, as it turned out, the chipmunks. The constant chirping and dashing about made it easy to step over time’s threshold and return to my 1790 Paradise.

Five canvas panels covered the shelter’s lower bents. I picked the sixth canvas piece up, draped it over my arm and walked around the wigwam. There was no question Ziibi Ikwe would be upset, none whatsoever.

Five canvas panels covered the shelter’s lower bents. I picked the sixth canvas piece up, draped it over my arm and walked around the wigwam. There was no question Ziibi Ikwe would be upset, none whatsoever.

In my defense, I saw the uneven bending in October, and it bothered me then. I untied the horizontal ribs and then the offending bents while the saplings were still green and supple. Try as I might, I could not get those west saplings to bend in the classic wigwam shape. I did the best I could and retied them—such is the nature of some wilderness classroom lessons.

When I finished the walk-around, I felt inspired. I wanted to continue with the next layer, but it was nearly 11 o’clock. With great reluctance, I walked back through time’s portal. But I was finally hanging canvas…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Hunting Camps, Wilderness Classroom

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Mountain Man, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional camping, Traditional Woodsman

4 Comments

“He made it through…”

An old doe snorted. The unexpected warning came from the far side of the big swamp, a ways uphill from the maple at the bend in the trail that hugged the swamp’s edge. The unmistakable sound rolled up and down the swamp like the thunder from a close lightning strike. Peering through the brush I saw two bounding white tails flag side-to-side on the mucky path that wandered to the south island’s east bank.

The air smelled warm, heavy with moisture waiting to fall at the first hint of dropping temperatures. Thick gray clouds hung low, but showed no sign of turmoil on that calm morning in mid-November, four days past the fifteenth, in the Year of our Lord, 1796.

Not long after first light a gray squirrel ventured forth. A fox squirrel followed. The two rodents scrounged in the brown leaves, but made little noise as the summer skeletons were damp and supple. Then a blue jay began an insistent hollering from atop an oak on the south island.

The snort came as no surprise. I heard many throughout the month; none directed at my humble existence. The deer appeared more cautious, looking about and lingering longer than normal. On one frosty morning, over the course of an hour, two young does attempted to cross to the south island three times, turning back each time due to some perceived concern. I supposed the two waving tails belonged to them.

A stout red oak limb, festooned with brown, dead leaves that clung to every twig, served as my fortress that morning. The parent oak stood on the south side of a small rise, nestled among a host of tight-packed red cedar trees, about thirty paces up from the swamp’s west edge.

Perhaps ten minutes after the doe’s snort, two ears twitched just over the knoll’s rise. A barren head popped up, then dropped down. The young doe was on the path that meandered upwind of the broken oak. I doubted she would pass without discovering my ambush, but she made no progress in my direction.

An older doe wandered downhill, then slipped out of sight. Four ears perked up, all intent upon the big swamp. The pair stood for a dozen minutes or more, gazing with purpose down into the tawny sedge grass. The closest set of ears, the youngster’s, turned north, listening in my direction. The fox squirrel was behind me at that point. I heard it, too. She turned back, then both heads jerked a hand’s width higher.

Even with bad ears, I heard the “splish… splish” of deer legs in the little creek. My eyes left the does. A foreleg rose and fell ten paces out in the sedge grass. The right foreleg stepped. That “splish” matched the movement. The oldest doe turned about and plodded back to the upper trail. After a long hesitation the younger doe followed. Out in the swamp, a thick neck watched.

In time, a second-year 8-point buck found his way to the scrape under a scrub oak, down the slope from my lair. He sniffed and pawed a bit, by then broadside at thirty paces. The Northwest gun’s turtle sight knew the location, but gave no mind; “Old Turkey Feathers” remained at rest across my wool leggins.

The buck did not freshen the scrape, but continued on his way with what little breeze there was at this tail. He slipped behind a bigger oak tangle where a massive, south-leaning fork crashed to the earth, bending over a dozen cedar trees with its burden. I pivoted a bit on the bedroll, but held the trade gun at bay. The buck walked into view a few paces from the swamp’s edge. He offered a superb shot, standing steady for several minutes as he surveyed the island. Then he flicked his tail and wandered out of sight.

Thoughts on Passing on a Fine Buck

I learned a valuable lesson late in my teens. The opening day of Michigan’s firearm deer season fell on a Saturday. For weeks I had patterned a nice seven-point buck. He was a first year deer. Back then the fawns came early, giving plenty of time for growth. Many of the young bucks developed fair first-time racks, most in the six to eight-point range—none of the spikes and three-pointers we have today.

I happened upon this buck’s habits early in November. He spent much of the day out in the river bottom. Back in the 1960s the whitetails moved from their night feeding ground to their day bedding areas up until 10 o’clock in the morning—none of the before dark/ after dark movement we have to cope with today.

Anyway, this fellow passed through the corner of the big woods on his way to the deep cattails at the river an hour after sunrise, give or take ten minutes. That morning was clear, crisp and sunny. I sat downwind of his favorite path and waited. I could taste his back straps.

He circled over the far hill on the early side of the schedule, showing no concern. He slipped into a little valley. I pulled the LeFever Nitro Special up and supported the double-barrel’s forestock with my elbow securely pressed into my left knee. My thumb twitched on the safety. I tried to calm my pounding heart.

“BOOM!”

My heart doubled its pace. I scrambled to my feet and began a fast walk straight to the muzzle blast. In hindsight it wasn’t my best choice, given my tender age and vulnerability in the situation, but that was my reaction. No one had permission to hunt the farm. With no second shot, I had a good idea what to expect. I saw our neighbor from down the road approach the buck, which was dead on the ground.

To add insult to injury, he called out for his son, who arrived about the time I was confronting this poacher. I kept a civil tongue, despite my anger and frustration. They never tagged that buck. The father just laughed and waived his shotgun in my direction as they dragged the deer off. It was a long, painful walk home. My father called the local Michigan Conservation Department post, but the deer was gone and nowhere to be found.

Some years later, we had a fine buck that frequented the farm about every three days. I wanted that deer and decided not to “waste my tag” on any other. I passed on a number of smaller-racked deer, and each time I did, I remembered the cruel lesson of that first seven-point. In essence, once the shot is not taken, there is no guarantee a hunter will ever see that deer again.

On that morning in 1796, I recalled my disgust with the neighbor and the painful lesson learned. A deep pang of anguish always falls upon me when I pass up a deer, followed a while later by a fit of second-guessing. I suspect those feelings result from the seven-point fiasco. I knew I might never see that eight-point again, but I also knew a good friend and his nephew were coming to hunt two days hence.

In our conversations before the season opener, Tom said Zach had never gotten a deer, and had had few chances in his brief hunting career. He held out high hope for his nephew’s first trip to the North-Forty.

As the buck walked off toward the south island, I kept thinking of Zach and how I wanted him to have a fair crack at that deer. Once he was gone, I settled back into my treetop fortress. A vague premonition swept over me, an inkling that I had just passed on my only chance to put fresh venison on the table. That 18th-century circumstance was too perfect; that eight-point buck gave me a half-dozen outstanding shots.

As it turned out, even with a fresh dusting of snow, the eight-point never checked his scrape line, at least not while Zach sat hidden in the cedars. It was a huge disappointment for me, but I knew the risks of letting a buck walk and the slim probability of him wandering by while Zach waited in ambush.

I never saw that buck again, and I attribute a large part of that to the whitetails going nocturnal. I never took a shot throughout November and December. But in retrospect, I would follow the same course a thousand times over, knowing Zach, or any first time hunter, was coming to the North-Forty. As a traditional black powder hunter, the historical me is not defined by the size or quantity of deer I stack up, or the number of times I choose not to.

In early March, maybe ninety paces up the hill and just over the ridge crest from that morning’s ambush, my wife, Tami, and I found the shed right beam belonging to that eight-point buck. Before we paused to say the usual prayer of thanksgiving for finding such a blessing, we both uttered the same words at the same time: “He made it through…”

In early March, maybe ninety paces up the hill and just over the ridge crest from that morning’s ambush, my wife, Tami, and I found the shed right beam belonging to that eight-point buck. Before we paused to say the usual prayer of thanksgiving for finding such a blessing, we both uttered the same words at the same time: “He made it through…”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

Posted in Deer Hunts, Worth thinking about...

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, historical trekking, Native captive, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “He made it through…”

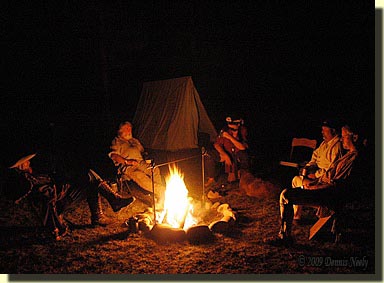

“North-Forty’s First Longbeard”

“Snapshot Saturday”

About four years after the first wild turkey flock wandered onto the North-Forty we had three gobblers and a couple of jakes. On a rainy morning, and with a day or two left in the season, the first longbeard in modern times fell to an English double barrel percussion shotgun, the same gun I used for sporting clays and quail walk competitions. What an unforgettable thrill…

Posted in Snapshot Saturday, Turkey Hunts

Tagged Black powder hunting, Dennis Neely, Mountain Man, North West trade gun, Northwest trade gun, trade gun, traditional black powder, traditional black powder hunting, traditional blackpowder, traditional blackpowder hunting, Traditional Woodsman

Comments Off on “North-Forty’s First Longbeard”